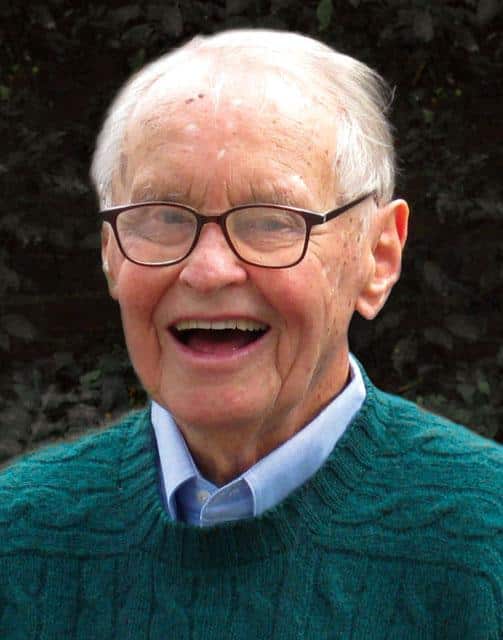

Dinghy Sailor Runyon Colie Jr.

As 98-year-old Runyon Colie was being introduced at the induction ceremony of the National Sailing Hall of Fame last fall, my mind wandered back to a race 47 years ago. It was 1966 and I was crewing with Sam Merrick at the E Scow National Championship. There were 60 scows lined up for the start on Lake Minnetonka, Minn., that year, and up until then no East Coast sailor had ever won the Nationals. But Colie, a Jersey Shore standout, had been consistently in the front pack.

The only other guy who could sail at Colie’s high level was the previous year’s winner, Buddy Melges. From my position on Merrick’s boat, I witnessed Colie win the start of the last race. Inside, I was cheering him on to win, and when he did, each of us who had traveled from the East Coast applauded. He’d won nine of 10 summer series races on Barnegat Bay that year, and although I was only 16 at the time, I was intent on finding out what made Mr. Colie so good.

At a local Penguin regatta a few months after the E Scow Nationals, I sought out Colie and asked the most simple question I could: “What does it take to win?”

His response was concise, and I can still hear his voice in my head. “Gary, if you want to win, just sail around the course more often than your competitors,” he said. “Make every minute count when you are sailing. Set a goal, and practice. I will watch you with interest.”

The man was a genius on the racecourse. Whether racing a Penguin or an E Scow, he was fast and always had a great start. He was extremely skilled at working his way to the favored side of the racecourse and avoiding incidents and hassles with other boats.

More than 100 of his family members and sailing friends traveled from Barnegat Bay to Annapolis, Md., to see this hero of New Jersey sailing inducted into the Hall of Fame. His inclusion is the recognition of one of America’s all-time greatest dinghy racers. The mission of the National Sailing Hall of Fame is to recognize outstanding contributors to the sport of sailing, those who inspire generations, and Colie certainly fits the mission.

He counts among his friends several of America’s greatest sailors, including Dennis Conner, who to this day says he regrets never being able to beat Colie in a Penguin. Buddy Melges, a fellow Hall of Famer, calls Colie “America’s foremost dinghy sailor,” and Peter Commette, an Olympic Finn sailor, refers to Colie as “the dinghy sailor.”

“His influence seems to course through the veins of every person that had the good fortune to sail with or against him,” says Commette, “and these people are passing his positive influence on to the next generation. Many find themselves quoting him when teaching others.”

A regular presence in New Jersey’s Barnegat Bay Yacht Racing Association for 92 years, Colie has won 18 class championships. His first local championship win was in the Sneakbox Class in 1934, and his last championship was in the E Scow class in 1994. That’s an astounding 60-year winning span. Colie’s E Scows were all playfully named Calamity, and his longtime boat number, MA 4, has been retired by the BBYRA.

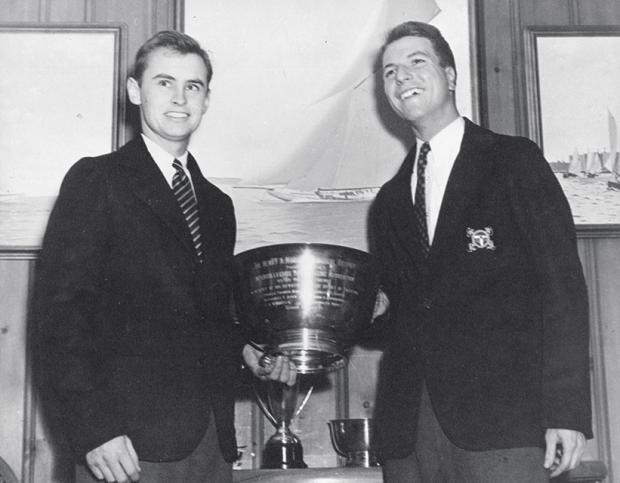

Beyond the shorelines of Barnegat Bay, Collie won Collegiate Nationals as a student at MIT in 1937, 1938, and 1939. When the International Penguin Class was introduced in 1938 it rapidly became one of the largest and most competitive small one-design classes in the world, and Colie won the International Championship title a record seven times between 1947 and 1962.

In 1960, he lost the 5.5 Metre Class Olympic trials to George O’Day by a single point. O’Day and his crew, Dave Smith and Jim Hunt, went on to win a gold medal at the Olympic Games in Rome.

Colie, still sharp today, enjoys sharing stories about his time as a blossoming young junior, including the one about the day when he capsized off Mantoloking YC, in his hometown, when he was very young. The Coast Guard came to the rescue in a small powerboat, with his mother chasing the Coast Guard in a rowboat.

There’s also the one about how he received regular assistance from an unlikely source as a junior sailor. “There was a fellow named Abe, who was the tennis man at the Mantoloking YC,” he says. “He would tell me what the wind would do on race days, and he always seemed to be right. Abe never steered me wrong.”

One of Colie’s most memorable moments was at an E Scow regatta that he was winning after the first day. On the second day he was unusually slow, and instead of being among the leaders, he was behind the fleet all day. When he got to the dock Colie discovered that his bilge boards had been reversed when they were reinstalled after polishing the night before. After that blunder Colie painted one bilge board green and the other red so his crew would install them properly.

While leading by a wide margin in another regatta, Colie realized he was sailing for the wrong mark. If he suddenly changed course, the trailing boats would cut the corner and sail directly to the mark and pass him. To deflect attention away from his intentions, he lowered the boat’s jib to make his competitors think he had a breakdown. Once the fleet sailed past, he hoisted his jib, sailed for the correct mark, and held on to the lead. It was a clever trick, but that was Colie—always smarter than the rest of us.