In 1964, Ched Proctor had a serious case of the slows. He was 14 and competing in Turnabouts in Scituate, Massachusetts, just southeast of Boston. “I remember coming in to the dock and being very frustrated,” he says. There was Bill Mattern, high school teacher, part-time garage sailmaker and unofficial mentor for the junior racing crowd. Proctor asked him what he thought of his sail. Mattern studied it and quickly confirmed the young sailor’s suspicion.

Seventy-five dollars later, with a new sail in hand, Proctor headed for Quincy Bay Race Week. Though he hadn’t been that competitive in his local fleet, he mustered the courage to sign up for the championship division—and won it. With that victory came an epiphany—at least for a 14-year-old—that would determine the trajectory of his life: “I learned then that a sail with the right shape makes the boat go faster.”

Professionally, Proctor would go on to work almost 50 years with North Sails, taking him to lofts in Wisconsin, Australia, Germany and Connecticut. Competitively, he would roll up an unparalleled list of one-design North American and National titles, notching 17 major victories in the Lightning class alone, including that class’s 2018 and 2019 North American Championships. A lot of the one-design sails North Sails sells today were designed by Proctor.

Proctor is a waterman who grew up on a bay in Weymouth, just south of Boston. He remembers, around age 5, spending time in an old, derelict rowboat in the backyard. “I pretended to row it using a couple of brooms,” he says. “It got to the point where I wore out the ground under the brooms and wore the bristles right off them. About that same time, my father tried to teach me how to sail and steer a boat upwind. I just couldn’t do it.” There’s a subtle shrug and hint of disappointment in his voice as he tells that story, and then concedes, “It seems that 7 is more the right age to learn that sort of thing.”

A few years later, he bought a Turnabout, paying for it by mowing lawns. “I gravitated toward sailing because all I wanted to do was be on the water. I was fascinated by boats, and I was too uncoordinated to do anything else. I just had no interest in playing other sports. I like to say I couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time until I was 15.”

His family purchased an International 210, which had a strong New England fleet. Mattern made them a genoa, but Proctor kept going back to him to make changes in the sail. “Finally, he said: ‘Here’s the seam ripper; it’s all common sense. Do it yourself,’” says Proctor, who estimates he recut that genoa close to 100 times. That experience led him to a job at a boat dealer, Multihull Associates, after graduating from Hartwick College in New York. The dealer set him up with a small loft area and a sewing machine, and Proctor started making his own sails and doing canvas work, a job not particularly in line with the economics major he earned at Hartwick. “I told my father I really wasn’t that interested in economics, and he said, ‘Well, you better figure out something that you’re interested in to make a living—maybe this sailmaking thing can work.’” With work at Multihull Associates tilting more toward canvas than sails, he decided it was time to seriously pursue the sailmaking thing.

He interviewed with John Marshall, who ran North Sails East, and Phil Mariner, who ran the now-defunct Hard Sails loft on Long Island, but the connection was really made through the International 470, which he had begun racing just before his senior year at Hartwick. The class was in its heyday in North America, and at one of its regattas, he met Peter Barrett from the North Sails loft in Pewaukee, Wisconsin. Barrett urged him to sail in the fall 470 regatta on Pewaukee Lake. With his Multihull Associates-branded sails, Proctor won the breezy Pewaukee event and was promptly offered a job at Barrett’s North loft.

As the 1976 Olympics were on the horizon, Proctor continued to focus on the 470, not an easy task for someone 6′2″. “I was trying to stay light enough to skipper the boat, and I got down to around 140 pounds,” he says. “It wasn’t a healthy thing.”

Then he met Australia’s John Bertrand, who was campaigning in Finns and would go on to win a bronze medal as well the 1983 America’s Cup. The Australian was in Pewaukee to learn the sailmaking business in preparation for starting a North loft in Melbourne. “One day, in the offseason, I was at Bertrand’s house, and we both got on the scale, him a Finn sailor and me a 470 skipper. We weighed the same.” It was 10 months before the US Olympic Trials for the 1976 games. “I thought, Oh my God! I need to get back on my diet.”

So Proctor resumed his routine of cabbage, vegetables and a lot of running. “That lasted a couple of weeks before the light went on. I thought, Even if I were going to win a gold medal, this isn’t worth it.” He went from 140 to 185 pounds and shifted his focus to the Finn. Greg Fisher, one of Proctor’s close competitors in the Lightning, says: “We were amazed he could go that quickly from one weight to another. But that’s Ched. That’s the kind of stuff he would do.”

While 185 pounds today is pretty light for a Finn, in the 1970s, singlehanders regularly wore water jackets, which quickly evolved from sweatshirts sewn together in the basement to commercially made vests that carried bottles of water high up on the body. “You could wear a maximum of 45 pounds of total gear,” Proctor says. “I would wear a thin wetsuit, some boots and four water bottles that totaled around 35 pounds. With that, I was competitive upwind.”

But like many others who shouldered the weight, it took a toll on his body. At the 1979 Finn Gold Cup in Weymouth, England, he carried four bottles. “I remember pulling the boat out of the water and lying on the beach for 10 minutes before I could get up and walk away from it.”

Today you can easily pick out Proctor ashore or on a boat by the pronounced stoop in his posture. He says it dates back before sailing. “My parents were always concerned that my posture was terrible. I remember being taken to different specialists early on to try to correct it. Sailing probably didn’t help. It’s so easy to hunch over while sailing. Even today, I’m always trying to make an effort to straighten out when hiking. I’m always complaining about crews who don’t hike out enough so that I have to hunch and tilt my head in to see.”

But getting the crew to hike way out isn’t just about his line of sight. Jay Meuller recalls sailing with him on a Thistle. “He would say, ‘Jay, if you can droop-hike all the way up this beat, we’ll be first at the weather mark by 100 yards.’ We’d get a good start, I’d be drooped over the rail the entire way, and sure enough, we’d have a big lead at the weather mark.”

These sails were from his private stock. He handled them like they were religious relics, which in his book, they probably are and have been since the first new sail he bought at age 14.

Meuller, who started crewing for Proctor in his early 20s, says: “He knows how to keep the boat constantly moving through the water, making it most efficient. He’s always paying attention to the balance, constantly looking at the draft of the sails and making a lot of minuscule adjustments that you wouldn’t think mattered, but every single time, they did.”

But it’s not all done through memory. “He writes down all these things on the deck—the setup, how fast we were going, how many seconds it took to get to full speed from a dead stop,” Meuller says. “By the time we were done, there was writing everywhere.”

Ched has been married to his wife, Judy, since 1984. She sailed with him before they started having kids, the two of them finishing second in the Thistle Nationals. Now they sail together mostly in Pequot YC’s Ideal 18s. “She steers. I give instructions and get frustrated,” he says. “She seems to enjoy that.”

They’ve had two children, Tom, who sailed in high school, but a Ph.D. in theoretical physics and his marriage sent him in other directions, and Charlie, who never stopped sailing. On the bulletin board in Proctor’s office is a photo of Charlie frostbiting with him in Interclubs at the Larchmont YC. The boat, No. 27, is sailing toward the photographer. Proctor is poised to windward in his customary pose, slightly hunched over, steering and trimming the main. To the leeward side is Charlie, wearing a yellow slicker and blue stocking cap. He’s focused on making sure his gloves are on securely. “He must have been 7 or 8,” Ched says, looking at it fondly. The two of them raced for three or four winters before they sold the Interclub, bought Lasers and raced in the frostbite series at the Cedar Point YC in Connecticut. Charlie had a successful run in Blue Jays on Long Island Sound, competing in a boat he rehabbed with his father’s help. In high school, he continued to sail but added cross-country running to his interests.

After high school, he was accepted at Tufts. Although athletics was not his primary reason for going there, he had talked to the cross-country coach as well as the sailing-team coach, Ken Legler.

“In June, the cross-country coach sent out a training schedule. It read: ‘Don’t worry if you don’t do 60 miles every week,’” Proctor says. “Ken’s letter read, ‘Have a nice summer!’ Charlie said, ‘I think I’ll go for sailing.’”

The young Proctor was a standout sailor over his four years with the Jumbos. “I think I always tried to impress upon him the importance of enjoying the effort,” Proctor says, “and the result would be whatever it is and not to worry a whole lot about the end result.”

But the end results have been exceptional. In 2016, Ched finished second at the Lightning NAs; in 2017, he was fourth at the Lightning Worlds; and in 2018, he won the Lightning NAs. Charlie, along with Meredith Killion, crewed for him. “Sailing with Charlie definitely increased the fun level,” Proctor says. “He was very organized and always dealt with things in a calm way. At one of the NAs, the vang broke just before the start. He calmly got out a spare piece of Spectra line, lashed it back together, and we were set. Something else failed at that regatta, and I remember him saying, ‘Dad, if you learn anything at this regatta, it should be that lines wear out.’”

In May 2020, Charlie was killed when hit by a car while riding his bicycle in Massachusetts, three weeks shy of his 28th birthday.

“That’s been one of the toughest things I’ve ever had to deal with,” Proctor says. “No one should have to face the loss of a child.”

I got a chance to sail with Proctor while he was preparing for the 2019 Etchells US Nationals. He and his crew, Chris and Monica Morgan, needed a fourth for some pre-event two-boat tuning, and I jumped at the chance. The boat was still on the trailer, with Ched studying the bow. Something was not right. His eyes settled on the two deck chocks.

“I don’t like things like that in my line of vision,” he said, pointing at them. So, Monica crawled under the deck with a wrench while Chris climbed out on the bow with a Phillips head screwdriver, and the chocks disappeared. Peace was restored.

Once on the dock, one of the biggest challenges was making sure the main and jib were removed from their bags and correctly unrolled to his satisfaction. He took care of unrolling and rigging the jib himself while we stood on the dock and watched. The main, however, required two people, so he enlisted me, and with a fair amount of instruction—”Don’t unroll it too fast; slower, slower; keep some tension on the leech”—we got it on the boom and hoisted. It was a far cry from the “drop, unroll and hoist” method I’m accustomed to, but, these sails were from his private stock. He handled them like they were religious relics, which in his book, they probably are and have been since the first new sail he bought at age 14.

Even though this was just an informal tuning session against one other boat, which wasn’t even in the water yet, we were in race mode the instant we left the dock. It was blowing around 15 knots, and with Monica on the foredeck, me just behind her, Chris on the main and Ched steering, we were all hiking hard. As the puffs came and went, it was clear that Proctor sensed them first, and he coached us through them: “OK, hike hard, now!” and then, “OK, relax!” With just a little advice, Chris had the main looking better than any Etchells main I’ve ever seen, and he had Monica squeezing the jib in slightly as we tacked and then easing it slightly out on the new tack, trimming as he got back on the wind. He was in his typical hunched mode and occasionally had to remind me to hike out farther so that he could see. But it was all done in a low-key manner.

“I think, over the years, I’ve come more to just enjoy the opportunity to compete and the people I sail with and not worry about the results too much—not take it too personally if I don’t do well,” Proctor said. “When I was sailing the Turnabout, where you needed a crew, I would have trouble finding people to sail with me. I remember my mother taking me aside and saying something to the effect of: ‘You need to treat people properly if you expect them to come back and sail with you.’ I think I took that to heart.”

Monica also crews for Proctor in his Lightning, and sailed with him in their 2019 Lightning North American win.

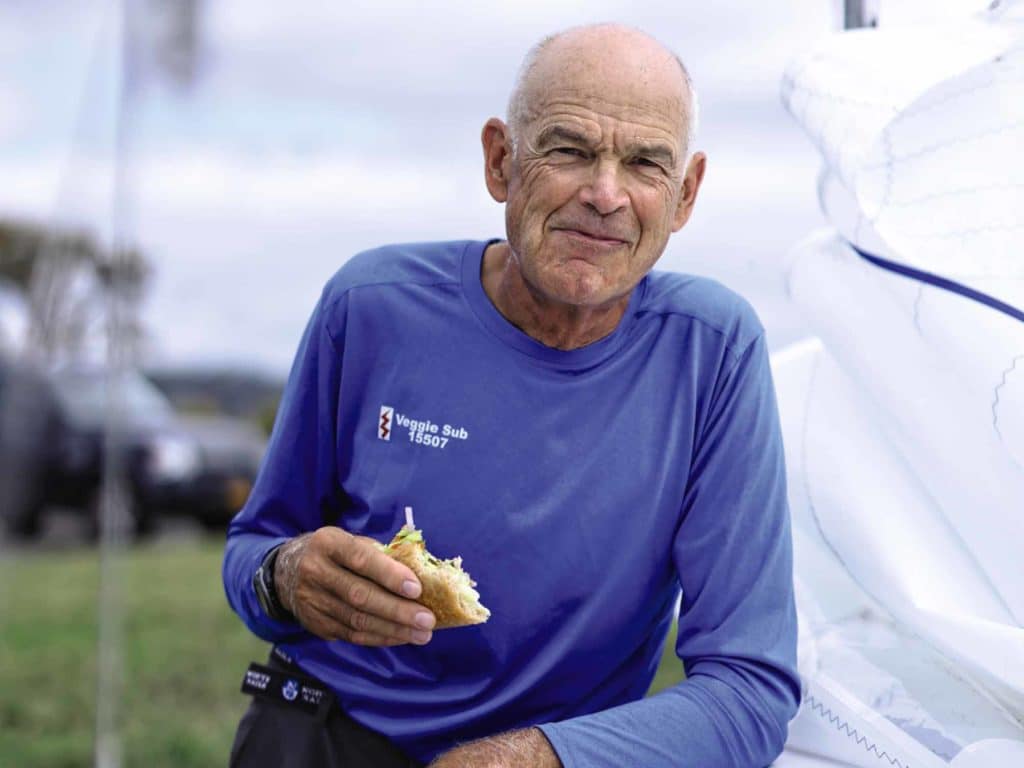

“Ched changed everything for me,” she says. “He made sailing fun for me again. He proved to me that you can sail and compete at a high level without losing sight of having fun. If we have a crappy race, we have a sandwich, an apple, water, then check the wind and focus on the next start. At the NAs, we had one or two bad races, but each time we just focused on moving forward.”

“He never gets frustrated,” Mueller says. “He just asks questions. He’ll even ask, ‘What are they doing that we’re not?’ and I’d say something like, ‘Their forward crew is hiking out a bit to leeward,’ and he’d say, ‘OK, let’s try that.’ He’s never negative. If we’re getting passed, he wants to find out why because his theory is that there really shouldn’t be a reason why we’re getting passed. And he knows that if you start talking negatively to your well-trained crew, you start losing focus on what’s going on outside the boat.”

He has always stayed true to dinghies, and there, the Lightning is at the top of his list… easy to transport, easy to rig, quick to put in the water and go sailing—and it’s lively, sensitive and somewhat intellectually challenging.

A couple of weeks before the Lightning 2019 NAs, at the Canadian Open, his boat flipped and turtled during a jibe. “I came out of that with my ego a little bruised,” says Monica, who was crewing for him. “I had never flipped a Lightning. But Ched’s biggest worry about flipping—other than, of course, maybe destroying our mast—was our peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. They were drenched. But he just said: ‘It’s OK. Get back in the boat.’ For his age, his energy was more than anyone I know. He was the first one back in the boat, ready to go, and said, ‘Let’s get the water out of the boat and see if we can pass some boats.’”

The appeal of one-designs runs deep for Proctor. Vince Brun, who worked for many years with him at North Sails, says, “Through my whole career there, Ched was always the Lightning guy, the Thistle guy, and all those types of one-design classes.”

Proctor, however, did some work for the 12 Meter Courageous in 1983. It wasn’t his thing. “I remember sailing upwind and thinking, this doesn’t seem like much fun. It’s about as lively as standing on a sidewalk.”

Newer boats? “I sailed a J/80 at Key West Race Week once. On that boat, people sit with their legs over the side, under the lifelines, and it always took a while to get organized to tack. That’s very frustrating to me. When I want to tack, I want to tack.”

Which is probably why he has always stayed true to dinghies, and there, the Lightning is at the top of his list. “The simplicity of the boat in terms of logistics—easy to transport, easy to rig, quick to put in the water and go sailing—and it’s lively, sensitive and somewhat intellectually challenging.”

Plus, he adds, “I think I’ve figured out how to make it go faster than most people, and that makes it fun.”

However, Proctor doesn’t keep secrets. In 1993, he came up with an innovative way to quantify tuning a Lightning. “Up until that time, people always looked at how much you blocked the mast partners. I realized that varies considerably based on the location of the chainplates, which there’s quite a wide tolerance on, so the mast doesn’t always sit in exactly the same place. I figured that it really had to do with thinking about the mast, the boat and the headstay as three sides of a triangle, with where the mast goes through the deck as one side of the triangle.”

The Proctor Measurement System is still widely used in the class.

More recently, at the 2019 Lightning Midwinter Championship, his team was out practicing in Miami with a team from Chile, which had a chartered boat that was not going well. They switched boats, made a few changes, and the team from Chile went on to win the regatta. “It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, I just sacrificed my own regatta and helped them win.’ Instead, he was happy he had helped them succeed,” Monica says. “A lot of people don’t do that. They just want to win. The selfless stuff he does, like this, often gets overlooked.”

“It wasn’t unusual for Ched and me to sit down together, even when we were rival sailmakers, and have a beer and talk about pretty much everything,” Fisher says. “On the racecourse, it was full-on, but it was always fair. When we would approach each other in a port-starboard situation, it was rare that either one of us would slam the other. It just wasn’t the way we wanted to play the game. When people get to the level of expertise Ched has, some people, you could say, earn the right to have a little bit of an attitude. But Ched is humble. He is one of the first guys to say, ‘Hmm…. Why do you do that?’ He’s always hungry to learn, to try new things.”

Proctor has long been teased about his ability to put food away, Fisher says. “I remember my wife and I, along with my father and Brian Hayes, going to dinner with Ched. As we all finished, one by one, we would all, without saying a word, hand our plates to him, and he’d finish up whatever was left. It just went around the table like that. We didn’t say a word.”

Now, at age 70 and recently retired from North Sails, Proctor is plenty active—usually biking 20 miles a day and running 3, maintaining a careful diet, reflecting on life, and, of course, spending a lot of time on the water looking at sails. It’s the Proctor way.