There is ice on the foredeck as the blue-wrapped J/7 with the No 1. on its mainsail glides to a smooth stop alongside the dock at Sail Newport (Rhode Island). Once secured to the cleats, the crew flakes the boat’s crisp Dacron main, snugs the sail ties and tidies lines that are piled on the cabin top. And as they move about on the boat’s wide side decks, removing toolboxes and personal gear, the boat barely rocks. Even at the dock, the new 23-foot daysailer from J Boats is remarkably stiff.

There’s a substantial white L-shaped keel and bulb hanging 3-feet-and-change below the hull, and to further illustrate the boat’s stability—an important selling point, says J Boats’ Jeff Johnstone—he grabs hold of the port shroud and steps onto the boat’s 3-inch wide molded toe rail. The boat leans a few degrees, but then stops.

“You wouldn’t see that on most 22-footers,” he says, perhaps comparing the company’s newest offering to the ‘ol tippecanoe one-design that has stood the test of time as J Boat’s smallest model. On this 2,300-pound J/7 there’s 1,050 pounds of lead in the bulb, which nets a 46-percent ballast ratio. The J/22 is down around 40 percent. All of which is to say the J/7 is plenty stable, so check that box if you’re looking for a ride that doesn’t tip over with every gust and scare the dickens out of your guests.

The simple and utilitarian J/22 is used extensively and for sailing lessons, rentals and world-class racing, and that’s always been the appeal for Rod Johnstone’s design from the early 1980s. That same ease and versatility is the pitch for the J/7 as well. “It’s all pretty simple,” Johnstone says, as he gives me a brief and frigid dockside tour in mid-December. The concept is jib-and-main sailing with the jib set on a furler and the main bent onto a deck-stepped single-spreader white powder-coated aluminum rig (the club edition rigs will likely be clear anodized, Johnstone says). All halyard cleats are mounted on the mast, including a swiveling cam cleat for the spinnaker halyard.

With regard to downwind sails, there is an option for a bolt-on short-sprit attachment for an asymmetric spinnaker package, and there’s a mast ring for a symmetric setup. Johnstone says a foreguy will do the work of twings, and while the demo boat did not have amidships folding padeyes for spinnaker-sheet turning blocks, that too will be a future option.

The racing sailor in us might immediately be looking for fine-tunes and inhaulers, but there’s nothing of the sort on the J/7. Jib sheets run through friction rings lashed at the clew to jib tracks and then straight aft to low-profile ratcheting Harken SnubberAir cabin-top winches. Cross or weather sheeting takes the line over the top of the stainless handrail without issue. The mainsheet is led through becket blocks on a Dyneema traveler bridle that is snap-shackled to padeyes, and then forward to a mid-boom block and down to a swiveling cam cleat base on a tall post. The adjustable backstay is split, led to cam cleats mounted near the aft edge of the cockpit seats.

With all the halyards and control lines confined to the cabin-top area and cascading down the companionway (there were no tail bags on the demo boat) the full length of the cockpit is clutter free. The cockpit’s long bench seating, with no lazarette hinges or associated hardware to sit on, easily fits four adults comfortably hip-to-hip on one side. Come nap time, on the hook or mooring, there’s more than enough length to stretch out. The “walk-through swim platform” looks to make it easy to get back aboard with a ladder and is a good space for wet lounging or lashing a cooler. The demo boat had an outboard bracket mounted to starboard, but without lazarettes the outboard will need to be stowed below, if removed for sailing.

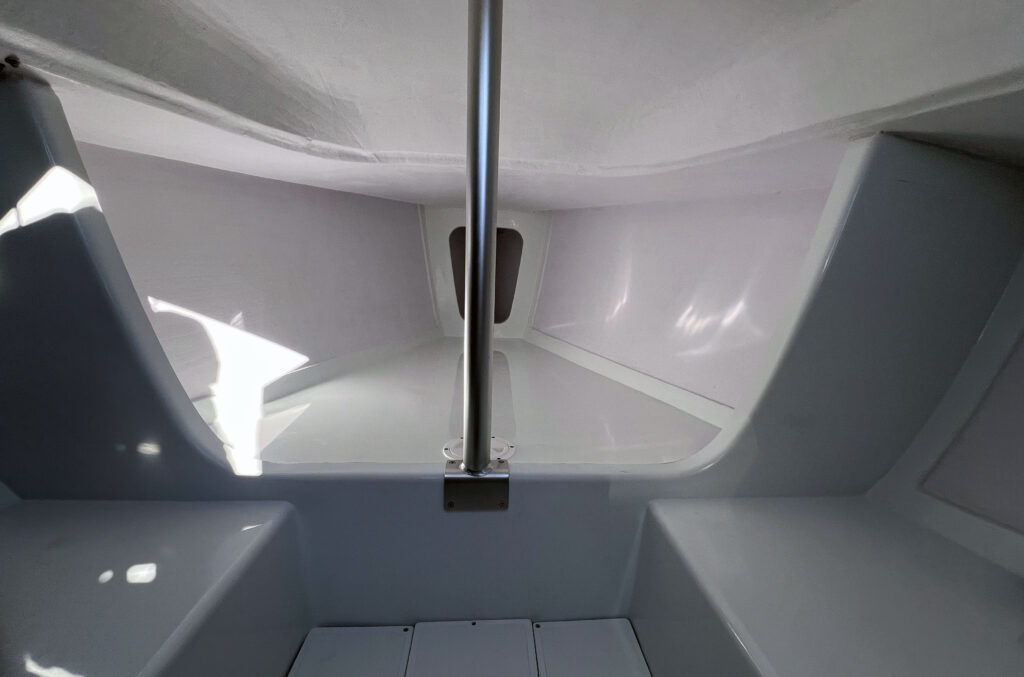

And speaking of belowdecks, while my demo mates hoist sails for our session, I slide down past the companionway slider and into a gleaming white cavity of minimalism. There’s a stainless-steel compression post mounted on the bulkhead, and forward of that is a proper V-berth for snoozing. The seating is low enough to sit comfortably (but not upright for me at 5’9”). There is certainly more interior volume than a J/22 or a J/70, and if weekend glamping is your jam, a boom tent, a porta-potty and a dry forecast will do you right.

Later, while sailing upwind in 10 to 15 knots of breeze on a bumpy Narragansett Bay, I slither below again for a listen and a sense of what the interior experience is like while underway. Aside from the normal sounds of water sloshing past the hull, the movement is a smooth and quiet rock-me-to-sleep kind experience. Sitting there below admiring the view makes me think about my longtime J/24 sailing mate and fellow yachting journalist Herb McCormick who is always the first to hit the rack on the long sail out to the typical Rhode Island Sound racecourse south of “R2.” I have no doubt he would approve of the 7’s nap-ability.

Back on deck, with our combined crew weight of roughly 600 pounds between the three of us, and everyone’s legs and bodies inboard, the boat seems to happily lock in and balance at about 10 degrees of heel angle. With its long and narrow transom-hung rudder, the boat turns quickly through tacks, and in a straight line, it tracks as if on rails. Perhaps, almost too straight. With the boat heeled, nothing happens when I push and tug on the tiller. Only when I pushed the tiller hard over to the end of its throw does the boat finally turn into the wind. It’s the same with bearing away. Adjustments to the mainsheet, however, do have immediate effect; a little ease into the puff levels the boat a few degrees and puts the bite right back into the helm. On a reach, the sensation is dreamy; the boat feels as though its sailing itself. Our top speed, according to my Garmin watch, is 7.1 knots upwind, and that’s without even trying.

The Johnstones have always been fastidious with hardware placement and ergonomics, and during my hour-long sail, I find the J/7 to be comfortable everywhere I sit: Driving from inside the cockpit, or outboard with my buttocks draped over the angled coaming; in front of the tiller extension or behind it, the sight lines are great because of the low cabin top and my feet come naturally to rest on the opposite seat. It’s all groovy, especially upwind.

I feel as if I could happily sail hard on the breeze for hours, but with a biting 32-degree northerly blowing across the deck, it feels wonderful and warm to finally turn downwind and into the low winter sun. Once on a deep angle, with the Windex pointing straight aft, the jib naturally wants to float to windward, and in the flat water of the harbor there is no fuss to maintaining the wing-on-wing. Playing the mainsheet straight from the boom, with a slight weather heel, the boat slides gracefully and straight downwind with barely a gurgle from the transom.

As a longtime J/24 and J/22 sailor I can attest that the true beauty of these two designs is the ability to casually harbor cruise in white-cap conditions with only the mainsail. The J/7 continues the tradition with the right balance and maneuverability no matter the sail combination. I try a mooring approach with the jib furled and there is just the right amount of momentum to glide six or so boatlengths before coming to a gentle stop. Backing the main by hand is very effective for a hard stop. And approaching the dock? Same. It’s highly responsive at slow speed and—bringing it full circle to Johnstone’s earlier display of its stability—when stepping from the boat to the dock (or to a launch), the boat stands mostly upright.

As for the price, the figures bandied about on our demo sail have the boat at $55,000 FOB in Bristol. Add in sails (including a downwind package because you know you’ll want it) and a trailer (it has a single-point lift) you’re at $65,000. Take a step further with a bottom job, an outboard, a proper cushion kit-out, canvas cover and other odds and ends, you’re at just shy of $70,000 for a complete package.

One-design class rules for main-and-jib racing, Johnstone says, are in the works, with the intent of having them fit on a single sheet of paper, but class racing is not the primary purpose. It will no doubt come, as will a PHRF number, but in the meantime, it can be enjoyed for a what it is: a simple way to get on—and stay on—the water.