Niklas Zennström’s new jet-black carbon-fiber race boat is likened to Darth Vader’s mask. Thanks to its color and angular looks, “Batboat” is another of the many compliments the craft has earned while turning heads in the waters off England’s south coast this summer. Indeed, Rán VII, the latest grand-prix machine for the Swedish technology giant, is showered with accolades; even Zennström praises his own craft effusively. “Honestly,” he says, “this is the most fun boat I have raced. Downwind I think it’s possibly faster than a TP52 or Maxi72. It just lights up.”

He’s right, and while Rán VII‘s results stand as proof of its quickness, anyone who’s chased it around a racecourse will wholeheartedly agree, you’d be hard-pressed to find a faster 40-footer today.

Grand-prix inshore yacht racing on the Solent, England’s sailing epicenter, is experiencing a renaissance that started with the advent of Fast40+ class racing, which initially provided an outlet for 40-footers retired from the Audi MedCup. The class has since spawned its own purpose-built breed, of which only two yacht designers are currently engaged — Jason Ker and Shaun Carkeek, both of whom have numerous Fast40s in their portfolios. Ker was responsible for Sir Keith Mills’ 2017 Fast40+ championship winner Invictus. Carkeek, the more prolific designer from South Africa, drafted Peter Morton’s previous two Girls on Films — the benchmark designs of 2016 and 2017. Rán has dominated the 2018 season, as has Carkeek, whose boats held the top four positions.

Five years ago, Zennström had Maxi72 and TP52 programs with personnel numbers approaching the scale of an America’s Cup campaign. He has since scaled back and dispensed with both, allowing him to focus strictly on the Fast40+. The shift is primarily due to time and convenience for Zennström, who is based in London, where he runs international technology investment firm Atomico.

“What really appealed to me with the Fast40+ circuit was sailing locally in the Solent, which is a fantastic sailing venue and next to where I live in Hamble,” he says. “Not having people fly around is better for the environment.”

Zennström also prefers that the Fast40+ is an owner-driver class, with pro sailors limited to five. Having sailed for years in the TP52 fleet, where the average crew is age 40 or older, Zennström also recognizes the difficulty for young sailors in gaining grand-prix experience. Consequently, five younger sailors make up half of Rán’s 11-man crew, alongside old hands Tim Powell, Steve Hayles and Adrian Stead.

While many of the other owners and teams in the Fast40+ circuit have graduated up to the class from less than grand-prix backgrounds, Zennström is one of the few to have graduated downward. While previous Fast40s were built to a cost, relative to a TP52, for example, Rán is a significant step forward in its development. It’s certainly the most advanced Fast40+ built to date, but Carkeek maintains there’s plenty more potential to explore. “There are things we could’ve done to make it more expensive,” he says, “but Niklas didn’t just throw unlimited budget at it.”

With Carkeek, the team keyed into the considerable development work, design and affirmation loops done over previous iterations of his 40s, dating back to the HPR40 Spookie for American Steve Benjamin, and before that to the GP42s he designed alongside Marcelino Botin. To build a quick Fast40+, the primary challenge is similar to a TP52: reducing and lowering weight in the boat while maximizing its righting moment. The rules and resulting solutions differ greatly between the two classes, however. The TP52 is a highly defined box rule, whereas the Fast40+ is an open box, relying heavily on IRC. Take weight, for example: The TP52 rule specifies a minimum limit (plus vertical center of gravity limitations on the mast, etc.), whereas the Fast40+ has no defined minimum. Instead, Fast40s must have an IRC displacement-to-length ratio of less than 110 (less than 90 for new boats) and an IRC TCC of 1.21 to 1.27. The TP52 rule includes a maximum bulb weight, whereas designers have found IRC’s sweet spot for Fast40+ bulbs at around 2,000 kilograms. Where there is much greater variation among Fast40s is in fin weight and vertical center of gravity.

With Rán, the team carved weight everywhere it could. Compared to its predecessor, Girls on Film, Rán is substantially wider on deck and slightly beamier at the waterline, yet is 162 kilograms lighter. The objective, says Carkeek, was to enable planing downwind in lower windspeeds, when they can be several knots faster than boats still in displacement mode. Overall weight is far from the whole story, however. Rán carries a substantially heavier fin, as well as 108 kilograms of internal ballast to comply with the Fast40+ rule. It is the first Fast40+ to have a solid milled steel foil rather than a typical steel strut with fairings, yet the boat still conforms to the IRC rating band and displacement-to-length ratio like other top Fast40s.

Several features have contributed to its light displacement. Most apparent is the giant chamfer around its foredeck. This isn’t a new concept, but a step forward from Girls on Film, one that offers several benefits. “Global stiffness, reduced windage and panel area, less volume, weight saving in the boat, less pitching, etc.,” says Carkeek. The chamfer is not carried to the transom because maximum beam at deck level aft helps optimize hiking crew weight.

A Fast40’s crew-weight limit of 950 kilograms on a boat displacing around 4 tons is a significantly higher proportion than that of a TP52 (1,130 kilograms on 6,975 kilograms displacement). Powell, Rán’s long-serving project manager and mainsheet trimmer, says the Fast40s are akin to dinghies. “The more active the crew is, the more you get out of the boat,” he says. “Every time someone moves across the boat you feel it.”

The most significant areas of Rán’s weight savings come from its structural optimization and build materials. It’s the first boat launched from Jason Carrington’s new Lawrie Smith-backed company Carrington Yachts (formerly Green Marine) outside Southampton. Despite Carrington’s excellent new facility, female tooling was made by the experts at Persico in Italy, out of milled carbon fiber. Carkeek says working with such a top-level builder benefited the engineering and design. “Usually you have to add margins in your weight estimate,” he says. “With Jason it was zero.”

Fast40+ rules attempt to limit cost by prohibiting honeycomb core on new builds. The rule doesn’t limit high-tech fibers, however, so Rán’s construction uses prepreg unidirectional intermediate-modulus carbon to optimize the structure over varying thicknesses and densities of Core-Cell foam. Due to its foredeck shape, the hull was built in two halves, joined down the middle seam. The use of intermediate-modulus carbon allowed them to reduce the number of interior frames required. Compared to Girls on Film, Rán has less transverse structure and more longitudinal.

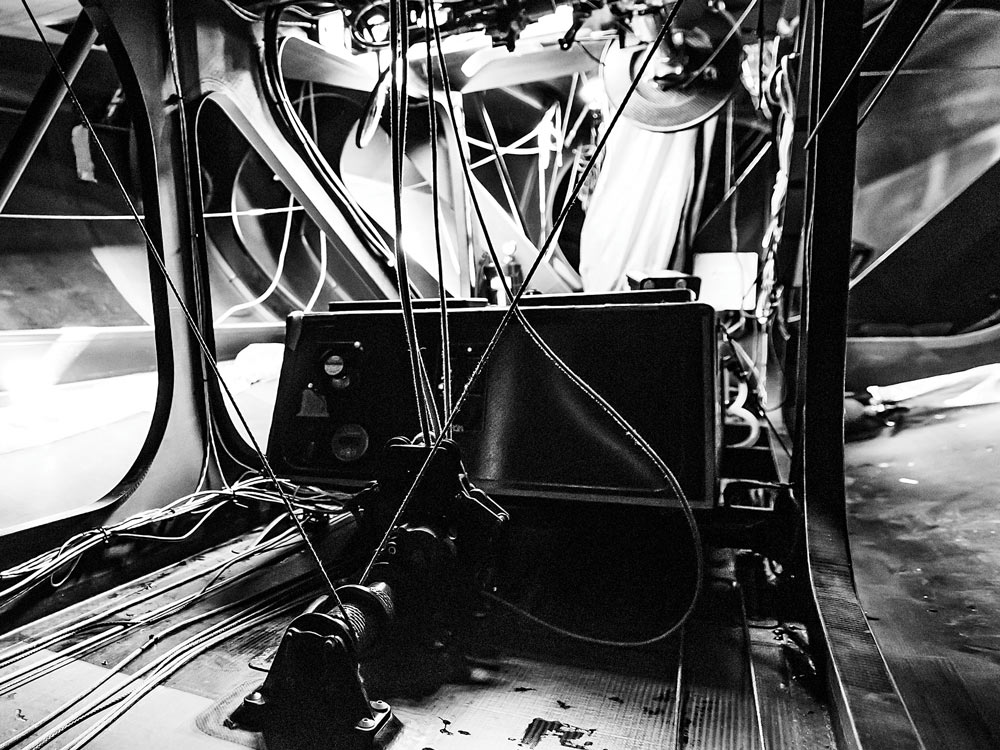

Another groundbreaking step is the boat’s electric propulsion. Currently being developed as a Zennström-Carkeek joint venture called EEL Propulsion, the aim is for these units to be standard fit on inshore race boats. Rán’s system comprises a tiny brushless 8.5 kW motor the size of a grapefruit, powering a compact saildrive built in carbon fiber and 3D-printed titanium. Two 150 kW lithium-ion batteries power the motor, each weighing 60 kilograms. While it experienced teething problems in its first season, the system is specified to drive Rán at up to 7 knots for six hours in certain conditions.

The engine prompted an amendment to the Fast40+ rule, which now includes a minimum engine and saildrive weight of 153 kilograms (including batteries in Rán’s case) and a minimum speed under power. In addition to its environmental credentials, the electric system offers extra benefits, such as battery positioning to optimize trim and allowing other systems to be run beneath the battery bank.

The boat’s shallow cockpit and low freeboard ensure Rán is unquestionably an inshore boat. “It feels very much like you are sitting on the boat, rather than in it,” says Powell. “In light air, you need to stay low to reduce aero drag.” One surprise, however, is the crew positioning. A helmsman usually sits aft of the mainsheet with the pedestal(s) forward near the trimmers. Rán’s configuration is reversed: The mainsheet trimmer sits farthest forward, with the helmsman behind him (necessitated by the rudder being so far forward) and the rest of the crew aft.

“I’ve had to buy a decent dry top because I am now the farthest forward,” Powell quips. This setup, along with a low-profile tiller that sweeps the cockpit sole, allows the crew to scamper across rapidly during maneuvers. In practice, they typically cross-sheet to keep the headsail trimmer to weather, a task made easier with the crew located aft. Otherwise, much of Rán’s configuration trickled down from the TP52s, including below-deck jib cars and furler for the spinnaker staysail. The Southern Spars rig has halyard locks, EC6 lateral standing rigging and a Carbo-Link forestay. It’s fitted with deflectors cranked up by a Cariboni hydraulic rotary pump, which is driven by the single Harken pedestal. Additional hydraulics adjust forestay and mast butt, but cannot be used during racing.

The boat is configured for spinnaker string drops, enabling the kite to be sucked through the foredeck hatch in the blink of an eye. The drop line does a lap of the interior before terminating on a take-up drum below, mounted on the port side. Having experience of this across their Maxi72s and TP52s, the Rán shore team, led by boat captain Jan Klingmüller, developed its own systems for this and the automatic below-deck reels used to stow spinnaker sheet tails.

Rán’s launch coincided with Harken’s latest carbon-fiber 600.3 winches, which offer a larger-diameter drum and higher line speed. These are used everywhere on the boat, except the forward trimming winches. Access to the interior, where there is barely sitting headroom, is via a hatch in the cockpit sole to port of the pit. The foredeck hatch is larger, with a pneumatic seal to prevent water ingress.

For sails, the team worked with North Sails designer Mickey Ickert. The racing inventory includes a single mainsail, two or three of their four jibs and three of their four kites, and code zero (for the coastal races), plus spinnaker and genoa staysails. The code zero and genoa staysail use Doyle’s cableless technology. Load cells are located throughout the boat (forestay, mast butt, deflectors, etc.) to help them reach their performance numbers quickly and repeatedly. This is accomplished by having a structurally stiff boat, says Carkeek. “If you tack and can reach full headstay tension quickly,” he says, “it means you get to target speed quicker.”

On the racecourse, Rán VII set the new benchmark out the gate. With an exceptional boat, a helmsman and owner who at one point was sailing as much per year as most professionals, and its world-class crew, the team won the first four events of the 2018 Fast40+ season. Although its price tag is confidential, it seems Rán VII might be the first 1 million euro Fast40+.

The rule has been left open, presumably to allow a boat such as Rán to raise the bar, and while history has demonstrated that boats making significant forward progress can kill classes overnight, Rán’s principals are intent on preventing history repeating itself. To this extent, Zennström has made Rán’s molds available to anyone who wants to use them. Imitation, it is said, is the best form of flattery.