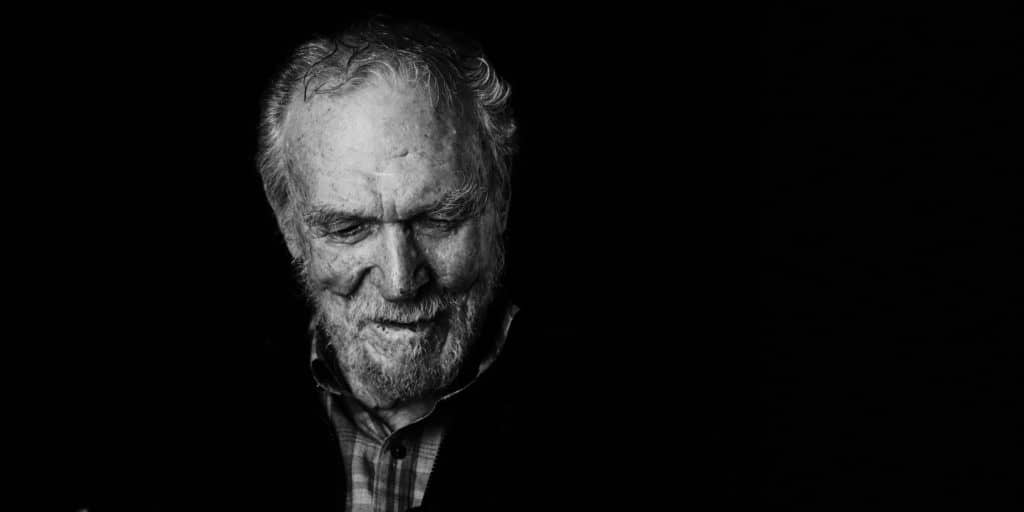

Editor’s Note: Upon finishing the recent Chicago YC’s Race to Mackinac, I opened my email to learn that the great Bruce Kirby had passed on July 18 at the age of 92. An amazing man he was, not only for his yacht designs and innovation, but for his incredible hand on the editorial helm of Sailing World in its early days. His columns were so sharp, eloquent and loaded with information that they remain a pleasure to read today. A true newspaperman, he was. “Young Dave,” is how he’d always address me on the phone, “you’re doing great work, but where the hell is my copy of the latest issue?” For some reason, he kept getting bounced off the comp list and I know it annoyed him to no end. Rightfully so.

We enjoyed many phone calls over the years during the torturous lawsuit over his Laser royalties, a battle that I’m sure brought great undue stress and robbed him of a few hard-earned golden years. “Happy to report Federal Court in Connecticut today awarded Bruce Kirby, Inc. $6.8 million settlement in our suit against Laser builders.—BK,” he wrote on February 14, 2020. That, I’m sure, was a happy day for the Kirby family.

Contributing editor Dave Powlison, who literally wrote the book on Laser sailing with Ed Baird awhile back, visited Bruce a few years ago to file the profile below. Once published, he did approve of the story and wrote: “Dave–Reports in from both sides of the border indicate you are the man. I’ve received nothing but very good chatter. Noroton YC is running the complete yarn, with pix on their website. We’ll have to do another on my 100th.”

He didn’t get to the century mark, but he will certainly be remembered as one of this century’s most important contributors to the sport. Sail on, Bruce, you will forever remain an inspiration and mentor.

— Dave Reed

Whether he likes it or not, Bruce Kirby’s legacy will be defined by one achievement — designing the world’s most-popular sailing dinghy. This one little boat is, of course, the Laser, and its story is the stuff of legend, having flourished from a rudimentary sketch in 1969 to an Olympic one-design class with hull numbers well into six figures. Every success story eventually has its final chapter, however, and for Kirby and the Laser, the conclusion is uncertain. Lawsuits over the little craft with which he’s most identified have consumed his golden years.

The topic of the protracted legal battle involving the Laser’s custodian, LaserPerformance Europe, is a toxic one in the Kirby household in Rowayton, Connecticut. Kirby, who turned 90 in January, and his wife Margo prefer not to speak of it, nor of the protagonists, for fear of more litigation. Instead, when I visit him in mid-December 2018, he reflects on the November 1969 phone call from Ian Bruce, of Canada, asking him to design a boat for a camping-gear company that could be car-topped, the now-famous sketch made during that phone call and the explosion of Laser sales that eventually followed. All led to what is arguably the pinnacle of the sport — selection as an Olympic class for the 1996 Games.

The Laser’s genesis, however, was no fluke. The seeds of Kirby’s design skills were planted long before. Born in 1929, Kirby grew up on the Ottawa River, which runs between Ontario and Quebec, where he first sailed on his father’s 24-foot Great Lakes Skiff class sailboats. Later, as a news editor at the Montreal Star, he says, “When there were lulls, I would draw boats on these pads that you put headlines on.”

After leaving the Star in 1965 to work for the magazine One-Design Yachtsman, colleagues at the Star kiddingly sent him a bunch of papers with doodles of boats they had made on them. “They were pretty bad,” Kirby admits.

“Even today, he still does sketches,” says Margo, his wife of 63 years and sole partner in their business, Bruce Kirby Inc. “He’s always drawing sailboats and hulls.” In their business, he designs the boats, and she does the all the rest. “I consider myself an enabler. I enable him to do his job.”

He carved boats early on as well. Pine was his material of choice and he melted down lead sinkers for his keels. At his Rowayton home, Kirby proudly carries one of his models up from the basement for me to see. He crafted it when he was 14. It’s a sleek sloop with white topsides, black bottom and a varnished deck.

“My aunt, who lived across the street in the summertime, had a beautiful piece of pine at the back of one of her kitchen cupboards to raise the smaller tins up so she could see them,” Kirby says. “I had been eye-balling it for a long time and finally asked her if I could have it.” He carved the outside first and then chiseled out the inside, being careful to leave the wood thicker around the keel than anywhere else.

“He won trophies every year,” Margo says. “He would go underwater and watch the boat move through it — as a kid. It’s spooky. Even today, he’ll look at a picture of somebody with a boat in the background, and it’s the boat he sees.”

The model in his hands shows an attention to detail well beyond his youth. There’s an adjustable mast step, handmade sails with broad seams to create proper shapes, and simple tensioning devices on the standing rigging. “It’s had different rigs,” Kirby says, “and this is about the third keel.”

He pauses and tilts his head to examine its underside as if observing water molecules flowing around the hull. “It’s one of the better hull shapes I’ve ever done,” he says. The rigging is loose, and he attempts to tighten the port shroud, fumbling in the process. Macular degeneration has robbed his left eye of most of its vision, so this is not an easy task.

“Now, don’t break it!” Margo cautions.

I lend a hand, and the rig returns to plumb.

If model-making and sketching were the practical elements of Kirby’s education, the academics were self-taught; he has no formal training as a naval architect.

“We got Yachting, Rudder and Yachting World,” Kirby says. “When I was supposed to be doing my homework, I’d grab a stack of these and pore over them.” At age 17, there was a pivotal moment. “My father borrowed a book, Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design, from the local doctor. I slipped it into my bedroom, and the doctor never got it back. I got most of my education from that book. I probably only understood about half of it, but I was just good enough in math to understand the rest.”

He still has the pilfered text, with the front cover inscription, “Medical Arts Building, Ottawa.”

As we walk through a short hallway to the dining room, he stops to point out a framed black-and-white photo leaning against the wall along the floor. “That’s a Beken of Cowes photo,” he says. Taken by the late Keith Beken, an icon of sailing photography, the subject is Kirby and his crew at the 1958 International 14 Team Race Championship in England. The lighting is spectacular; the moment captured is quintessential Beken. But it’s all about the boat. Kirby critically notes, “We didn’t have enough vang on there.”

This championship, he says, was one of the most emotional moments of his life, one that would propel him into the ranks of professional designers. He tells the story in vivid detail: In the regatta’s final and decisive race, he and his Canadian teammates face a New Zealand squad whose boats are better in strong winds. The Canadians struggle on the windward legs, barely hanging on against the faster Kiwi boats. By the final downwind leg to the finish, the race committee is recording puffs up to 30 knots, and through attrition, each team is down to two boats. Kirby and crew, Harry Jemmett, lower their mainsail so only about 12 feet remain aloft. Jemmett sits to leeward, desperately trying to steady the leech while Kirby, on the other side, wings the jib. Because of a heavy mist, he’s unsure where the other Canadian boat is. Kirby finishes first, followed by one of the Kiwis, while the second New Zealand boat, sailing with a cracked mast, is working its way downwind with only a spinnaker.

“I lost sight of our third boat, when it suddenly appeared out of the mist, going like a bat out of hell,” Kirby says. “He had rounded the weather mark, didn’t hoist his chute, reached off and then jibed and reached back. He beat the second Kiwi boat by 50 yards, and we won the event.

“I wasn’t in one of my own 14s in that regatta,” Kirby says, “but it was because of that race that I went home and immediately started designing what became the Kirby Mark I. That was in late 1958. The idea was to create a boat that could beat the Kiwis, but we never came up against them again.”

The Canadian team did win the next team-race championship, two years later, and had good upwind speed in stronger breeze. Over the next 12 years, the Mark I would be followed by four other Kirby 14 designs.

“I recently learned from a 14 buff that for the two or three years the Mark V was being built, no one was buying any other designer’s 14,” Kirby says.

Bruce Kirby the designer had arrived.

One of the things that thrills Kirby most is the number of times he’s had strangers tell him how the Laser changed their lives.

The International 14 era also marked the beginning of his partnership with Ian Bruce, who owned a small company in Pointe Clair, Quebec, about 20 miles south of Montreal. Bruce built Kirby’s 14s in fiberglass, beginning with the Mark III.

After their November 1969 phone call, Kirby took his sketch home and drew a full set of lines on mylar drafting film, then followed with deck, daggerboard, rudder and sail plan for the yet-to-be named boat. He sent a copy to Bruce and kept one copy for himself. But then the camping company changed its mind — they didn’t want a sailboat. “I still have a letter to Ian, saying, ‘Hang on to the design. That little boat might make us a buck someday,’” Kirby says.

In Kirby’s basement, I watch as he rummages through drawers in a metal draftsman’s cabinet. “I know it’s here somewhere,” he tells me. We go through five or 10 drawers before he finally says, quietly, “Here it is.” Lying in the drawer, on top of some of old photos, as if randomly tossed there, is a large manila folder with neat draftsman’s lettering, “Laser, Original Lines, 1969 and Sketch.” He hands me the folder, and there they are. It’s almost like being in the presence of some sacred relics, which, in a way, I suppose they are to the more than tens of thousands who sail or have sailed the boat. I keep waiting for a beam of sunlight to come streaming through the basement window to illuminate the moment.

The design sat on the shelf until 1971, when Kirby’s magazine, One-Design and Offshore Yachtsman, decided to hold a regatta for boats costing less than $1,000. The regatta was held at the Playboy Club on Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. “I called Ian and asked if he could get a prototype of that boat made in time for the event,” Kirby says. “He said, ‘I’ll build two of them, and we’ll tune them up together.’ But he barely completed one.”

With the boat atop his car, Bruce drove from Montreal to Toronto, where he picked up sailmaker Hans Fogh, who had an untried sail for the new boat tucked under his arm. Off they went, driving through the night to Wisconsin to what was called the America’s Tea Cup, while Kirby flew in from the East Coast.

“The next morning, the three of us put the boat together on the beach. It was the first time the mast had been in the boat,” Kirby says. Fogh built the sail relying only on his experience with Finn rigs. He had not even seen the spars before they arrived in Wisconsin. There was one race the first day, and that evening, Fogh went to Buddy Melges’s loft, recut the sail, and the next day the boat handily won the first race. Then, with a significant lead in the next race, the regatta was called for lack of wind.

“It was quite decidedly the fastest boat there,” Kirby says. Still, the boat also had too much weather helm, so he and Fogh adjusted the sail plan to move the center of effort forward a few inches, shortened the boom 4 or 5 inches and raised the mast to keep the sail area the same.

The next stop for the boat, now officially called Laser, was the New York Boat Show in January 1971. “The success at the Boat Show gave us a hint of what was to come,” Margo says, “although it didn’t really sink in then. We thought, ‘How could this be?’ Those things don’t really happen.” She quickly organized a class, forming the first Laser association in the states, and hosted one of the first Laser regattas in Connecticut, where the magazine was located. Competitors from Ottawa camped in the Kirbys’ backyard.

RELATED: Bringing the Laser to Life

Several years after introducing the Laser, Kirby got a call from Dennis Clark, of the Clark Boat Company in Seattle. They had built some of Kirby’s Mark IV 14s and wanted to know if he would design a quarter-tonner for them.

“I had never designed a keelboat, so the first thing I did was call [C&C designer] George Cuthbertson,” Kirby says. “I didn’t want help designing the boat, but I did want help creating the measurement certificate. He sent me certificates for two or three boats in that range, which helped me figure out the righting moment and how that influenced other things.”

The result was the San Juan 24, of which 1,200 were built. “The IOR people put out a book every year that lists all the boats that have been measured for a certificate,” Kirby says. “A while back, I discovered that the San Juan 24 was the most measured boat in the world for a few years in the 1970s. It was a big thing in those days.”

In the past year, Kirby has been communicating with a Dutch sailor who reports that San Juan 24s are raced in Europe. But the strangest San Juan 24 story was from many years ago when, according to Kirby, “some madman from California sailed one from Los Angeles to Honolulu by simply following the paths of aircraft flying the route. With scores of planes going to and from Hawaii, day and night, and with no other place for the planes to go, navigation was not a problem.”

With three reputable designs to his name, Kirby left the magazine business in 1975 to pursue yacht design full-time. And, of course, continue sailing. He raced Lasers intensely for a few years, finishing sixth at the 1972 North Americans on Lake Geneva and fifth at the U.S. Nationals at Brant Beach, New Jersey, the same year. A plastic cube trophy from the North Americans sits on one of his office shelves. “They still owe me a cube for the U.S. Nationals,” Kirby says.

His other trophies are relegated to the basement, laid out across two 7-foot tables that once served as drafting surfaces for many other noteworthy designs, including the Sonar and Ideal 18. “The two tables were beside each other, and especially in the 1970s and 1980s, when I was most busy, I would often have a boat on each board,” Kirby says. “If I got bored working on one, I’d go to the other. The 12 Meters, in particular, were so full of very, very fine calculations that it was a nice break to go to the other board and do a 14.”

Kirby designed the 12 Meters Canada I and Canada II for the America’s Cup, the latter of which is represented by a large half-model hanging in his dining room — a white hull with a bold, red horizontal stripe just below the sheer line, interrupted only toward the aft end with the Canadian maple leaf.

“We never really had enough money,” he says. “We were going to build a new Canada II, but we couldn’t afford it, so we took Canada I and put a winged keel on it. There was no science behind it. It was just from having seen the Aussie boat.”

Kirby’s Canadian heritage runs deep, having represented the country in three Olympics — twice in the Finn (1956 and 1964) and once in the Star (1968). Recently, he was awarded the Order of Canada, the country’s second-highest honor, for his contributions to sailing. He’s met Prince Charles and Queen Elizabeth, again, for what he has done in sailing. There are few boxes left for him to check.

One of the things that thrills Kirby most is the number of times he’s had strangers tell him how the Laser changed their lives.

“The first time that happened to me was maybe 20 years ago,” he says. “A fairly young kid came up to me and said, ‘Thank you for saving my life.’ I asked, ‘What?’ He said, ‘I was headed down the wrong path. I was on drugs, and I knew where that was headed. But a friend of mine grabbed me by the back of my neck and said come here, I want to show you something. And he took me to the local lake and said, you need to learn how to sail one of these.’”

Recently, at Connecticut’s Cedar Point YC, a Swedish sailor approached him to share a similar story. “These fellows who sail the boat today do it at a much higher, more intense level than I ever did,” Kirby says. “These guys start at 17, and it becomes a major part of their existence, winter as well as summer. It’s really upper crust for people to come up to me and tell me that.”

These are the highs, but there have also been plenty of personal low points associated with the Laser. In the late 1970s, Kirby and Bruce had a falling out, largely over financial matters. “He should have made a lot of money on the boat, but he was hardly ever out of debt,” Kirby says. “I thought he should have charged more for the boat that first couple of years — maybe $720 — and people would have still bought it. Instead, he insisted on the low price of $695. Plus, marketing was basically Ian’s show, and he was not a businessman. I was always beating on his accounting department. I knew that was better than letting it slip and go altogether.”

Bruce died in 2016, and Kirby admits he didn’t know he was ill. “Maybe,” he says with a tinge of regret, “it would have been better if I had been able to at least call him.”

Then, there is 2010, when he discovered he had macular degeneration. As the fear of going blind weighed heavily on him, he says, his royalty checks for the Laser stopped coming. Soon, he found himself embroiled in a protracted, eight-year legal battle involving LaserPerformance Europe, its principal, Farzaad Rastegar, the International Laser Class, and the International Sailing Federation (now World Sailing).

The intricacies of the case are Grisham-worthy, and suits and countersuits followed until the judge ultimately ruled in favor of LaserPerformance in 2018. Litigation continues, so Kirby is reluctant to talk about it, but he and Margo wear their feelings on their sleeves.

“We would have had a different life if this hadn’t happened,” says Margo. “But we have survived the anger, the disappointment. I couldn’t believe they would do this to him after what he’s provided for them, for decades. But I guess when money’s involved, everything else falls away.”

Kirby says, “It’s funny because I don’t remember anger — I remember disappointment.” What will happen next? “Nobody really knows. We don’t speak to anyone anymore and haven’t for some years. It’s so complicated that I don’t really have it clear in my own mind right now. The whole thing breaks my heart, to see something that was so great go completely bad. I’m probably owed about a million bucks from this, but I don’t think I’ll ever see it.”

It’s a sunny day in Rowayton, just a few weeks before year’s end, but it feels more like the middle of October. I’ve just finished lunch with Kirby at Brendan’s 101, one of his favorite lunchtime haunts. As I hold the door for him to pass through ahead of me, he says quietly and with a subtle smile, “You know, people usually go in front of me — so they can catch me if I fall.”

But it’s no joke. His pace is slow and deliberate. After years of hiking on International 14s, Lasers, Finns and Stars, his knees are shot, he has a broken back and he wears hearing aids.“It’s kind of strange,” he says in a somewhat baffled tone, “because no Kirby male has lived anywhere near this age.” His brother died at 42, his father at 58.

Yet, he remains sharp as a tack. He’s been working on his memoir, and says he still has two more chapters to write.

“Whether I’ll ever finish those or not, I don’t know,” he confesses. “I do find myself searching for words, and they’re not always there.”

The last boat to come off Kirby’s drafting board was a 38-foot yawl for author and magazine alum Nat Philbrick, in 2010.

“Part of it is my eyes,” Kirby says when asked if his design days are over. “If somebody came along with something I’d really like to do, and it’s a person who would be nice to work with, I might give it a try.”

As for sailing, it’s all memories at this point. On the Kirby fireplace mantel is a framed photo taken in Vancouver of a Laser on a mad reach, the skipper hidden by spray, but the sail’s nationality letters are clear: CAN. I ask his thoughts when looking at it, and without missing a beat, almost as if he knew what I was going to ask, he says, “I’m right in that boat. I can feel it immediately.” Then he adds with a wry smile, “Only I’d probably be rolling over to windward.”He studies the photo a bit longer.

“I’d just like to be out there. And, of course, to be as far up in the fleet as possible.”