The advent of Code Zero sails more than 20 years ago set off a revolution in offshore raceboat performance. Paul Cayard’s team on EF Language in the 1997-98 Whitbread Round the World Race, with North Sails, is often credited with the first high-profile development and use of these sails, helping them take the overall victory in the race.

Meanwhile there were parallel and more-modest efforts being made elsewhere in the racing world, including Denmark, at the hands of Elvstrøm Sails CEO Jesper Bank.

“We were having a good time sailing locally in a 34-foot boat of mine that we kept trying to supercharge with more and more sail area to get through the typical light air of these races,” says Bank, an Olympic gold medalist and America’s Cup skipper. “We had this idea of building a Code Zero, which was just the talk of the very elite of sailing in those days. Not many knew what such a sail would even look like, and for sure no real sailcloth existed for it.”

He and colleague Ken Madsen happened upon a few rolls of a bright-yellow, light laminate. From this, he says, they built what they believe was the first Code Zero in Denmark and used it in a 137‑mile distance race around the island of Fyn.

“We were lucky we could fly that sail for 40 percent of the race, and that gave us a first in class, and if I recall right, third to finish after some of the much bigger boats in Denmark,” Bank says. “It was fun to be at the leading edge.”

From the start, it became clear that when the conditions matched the range where these sails could be used, the boat became turbocharged and disappeared over the horizon.

The reason for their effectiveness is simple: These masthead-reaching sails fit perfectly into an important niche in the sail-selection matrix—where fractional, nonoverlapping jibs can’t provide enough power and asymmetric spinnakers are too powerful.

As these sails have evolved in design and use, it’s become surprising how large an area they can occupy in the selection chart: from a relatively narrow range of tight-reaching angles in light air to expand rapidly as the breeze strengthens.

An important aspect in their development was how to design them so that they fit within existing class or handicap-rule frameworks. Because they have a free-flying luff, Code Zeros do not fit the definition of a headsail whose luff is attached to the headstay, so they therefore had to somehow fit within the definition of a spinnaker.

In the Whitbread 60 Class, the definition required the sails to have a midgirth dimension of no smaller than 70 percent of the foot length, in Denmark; in the DH rule, it is 65 percent; so these became the lower limits in size and flying shape available to sail designers.

Many rating-rule authorities set their minimum girth definitions at 75 percent to impose some limits on the new sail’s development path and range of effectiveness. At this relatively large size, only boats with stout rigs to handle the loads and a robust righting moment could push the sail toward tight headsail angles, and when used at broader angles; then the A3 as the conventional reaching spinnaker would be considered.

However, such limitations did not stop development at the grand-prix level, where an increase of speed at any cost is fair game for exploitation. In classes such as the Maxi 72s that race in venues where there is plenty of non-VMG sailing around islands and the like, a properly developed masthead Code Zero could easily become a race winner.

The challenge, however, has been to meet the minimum-girth requirements and still have an effective flying shape and stability in the angles between the headsail and the A3. With a tight luff, the shaping geometry becomes difficult without having extra sail on the leech.

In the past year or so, sail designers have reoriented their thinking to explore flying shapes that allow the luff to sag more than a sail whose luff is supported by a tight cable.

At tight sailing angles, this extra sail area could not be flattened enough because of the minimum amount of girth needed to meet the rule.

Various tricks were devised to try to reduce the annoying flapping leech that was stealing laminar flow off the back of the sail. Some teams resorted to building fractional Code Zeros (“Fr0s”) to fill this niche at tight angles where the masthead sails were too deep and too powerful.

So, two Code Zero sails were becoming part of what was already a highly complex choice of reaching sails available to the offshore racing yacht: a masthead Zero or A3 spinnaker for broad angles; a Fr0 for tighter angles; a jib top; a blast reacher; or a genoa staysail for even tighter angles. Some teams are even experimenting with a high-clewed flying headsail flown off a tack pennant on the bowsprit to make it three sails forward of the mast: the reaching headsail, the upwind headsail and a small reaching staysail.

Imagine the groans over the cost and complication, not to mention the bulk and weight of all these sails. Not many racing programs can handle this load.

Then came a flash of inspiration: Why assume a tight luff is needed for an efficient Code Zero flying shape?

In the past year or so, sail designers have shifted their thinking to explore flying shapes that allow the luff to sag more than a sail whose luff is supported by a tight cable.

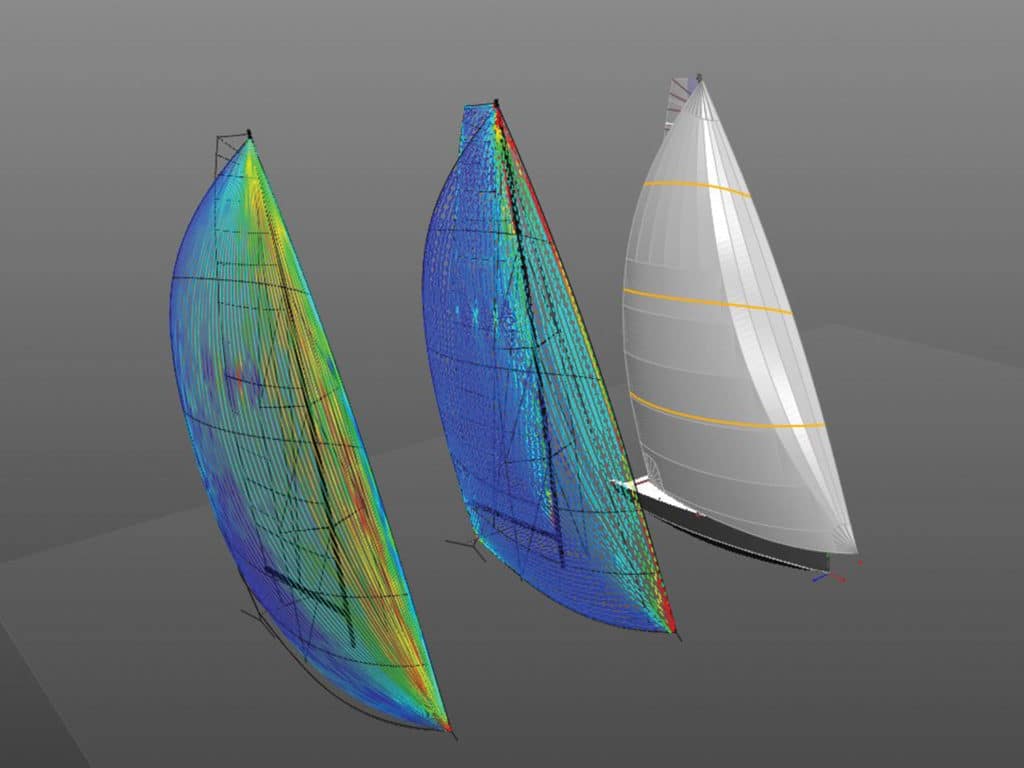

This change in geometry is accompanied by reconsidering the structural elements of the sail to better accommodate the loads within the sail itself. With fiber-reinforced cloth, this becomes a matter of laying in enough carbon and aramid to match the loads calculated through an analysis of the stress vectors in the sail.

The loads are determined by the size of the boat and its stability, as well as the size of the sail itself, and the max loads it sees varies with wind speed and angle.

“By placing high-strength fibers along the catenary load lines,” says Glenn Cook, of Doyle Sailmakers, “we can achieve great strength and stability for the desired mold shapes. This has also allowed us to better flatten the exit shapes for more efficiency” and reduce that annoying flapping of the first‑generation sails.

JB Braun of North Sails points out that custom-designed sails built with tapes or fibers are not necessary for building good Code Zeros, thereby offering a solution for those more budget-conscious owners interested in this performance upgrade.

By using conventional laminate materials cut and assembled in panels, the cost is lower without significant compromise in weight, strength, longevity or mold-shape performance.

“We’re actually developing a new program to help with creating more-efficient panel layouts of these sails,” Braun says, “because they are neither spinnakers nor headsails, and therefore have unique loading characteristics. We use a specific range of what we call Code sail material that is engineered with the right denier and film appropriate for various boat types and load requirements in the sail. We’re very excited about this because it will make Code sails more accessible to a broad range of users, racers and cruisers, who will benefit from the added performance these sails provide.”

Whether built with panels or strings or tapes along load paths, going without anti-torsion cables also vastly reduces the attachment loads on the luff of the sail, making expensive and complex reinforcement of the bowsprit or pole less necessary, as well as reinforcement at the top of the spar at the masthead halyard exit. Large furling J0 sails on the new generation of luxury performance multihulls shows this, particularly on catamarans, where a great amount of headstay tension would require lots of structure in the forward crossbeam to handle this load.

“On a TP52, we calculated the difference to be almost 400 percent on a masthead genoa,” says Quantum sail designer Chris Williams. “Without a cable, the load is calculated to be about 1.1 tons, and in a cabled sail, this load is about 5 tons.”

He also says luff tension then becomes a shaping tool for achieving the right flying shape in varying conditions.

“At tight angles in light air, the luff can be loosened 30 to 50 millimeters [Ed’s note: an error in the print version of this story has been corrected with a change from centimeters to millimeters] to allow the luff to rotate, flatten and present a fine entry angle at the luff,” he says. “Then, as the breeze comes on, the luff can be straightened to allow more twist off the leech for depowering. At broad angles, when the wind is strong—and you’re still not ready for the A3—the sheet and luff can be eased to rotate the sail to windward for the best projected area.”

On the practical side, flying a zero without a cable is not complicated: Hoisting the sail is easy when rolled up on a furler system, and the tack will be attached somewhere strong forward of the forestay.

The sheet block will locate on the shear at a position determined by the clew height or through the spinnaker fairlead with a tweaker. A pad-eye or looped attachment at the tack can have a shackle and block for a 2-to-1 tensioner system for the luff with the line led aft to a winch and clutch to adjust the luff tension under load without having to move the halyard from its full-hoist position. With a bottom-up furler and the sail unloaded while furling, it should rotate as quickly as a staysail or headsail furler, then either doused into a bag like a flaked spinnaker or kept up if sailing shorthanded or conditions are variable and it might need to be redeployed quickly.

It’s worth noting that measurement-based rating rules such as ORC and ORR now allow these sails to have between 55 and 75 percent midgirths, and therefore have a more efficient shape. They’re known as “Headsails Set Flying” in ORC parlance and “Tweeners” in ORR lingo. They are appearing more and more among the high-performance offshore boats, often as a masthead genoa to be used in light air that approaches VMG upwind angles.

All sailmakers seem to agree that these sails are an enormous step forward in near-reaching performance; in light air for some boats, the sails are already being considered suitable for upwind performance. Williams raced with Bob Hughes’ Heartbreaker in both the Bayview Mac and Chicago-Mac races, and reckoned they used this sail for two-thirds of the Chicago YC’s and one-third of Bayview race’s because of the light air.

Cook makes an even bolder prediction: The future is headsails without cables at all. “The headstay will be needed only to support the mast,” he says. “These sails on furlers can efficiently deliver power, performance and ease of use not seen before.”

Jonathan Bartlett, of North Sails, points out that the trickle-down effect of these sails from the grand-prix to the local fleets is already happening.

“There are a lot of Code Zeros being used in the Wednesday Night races [in Annapolis],” he says, with these races getting the strongest turnouts.

“We are also transitioning back to point-to-point racing on the weekends and away from windward-leewards in the handicap classes,” Bartlett adds. “Some have been shy about committing to them due to the six-second hit in PHRF, but if you have the conditions, this is worth it. And our use of ORC in these races has allowed a fair treatment of these sails in rating.”

In all, he says, the new generation of Code Zero sails have opened up a whole new range of fun for any boat—not just pure raceboats—which is energizing those owners who want to race but don’t have the ideal sails to make it a worthwhile pursuit.