The one overriding theme is to increase race participation, and in order to do that we need to allow a program to enter the race relatively late without a competitive disadvantage. We also need to allow teams to come in with a lower skill level or smaller physical stature, e.g., women and smaller individuals, and still have them feel competitive.

Safety has been another area of major focus. Organizers promote the adventure aspect of the race, but they don’t want anyone hurt, or the boats to break, so one of the areas we focused on was water protection on deck. The cabin, for example, is shaped so that it sheds water, and the freeboard of the boat is very high for its length. By comparison, the Volvo Ocean 65 has the same freeboard at the stem as a VO70, and significantly more freeboard amidships. In my opinion, we need the boat to be wet because that’s the sort of imagery the race thrives on, but what we don’t need is forceful green water washing out the sailors’ legs.

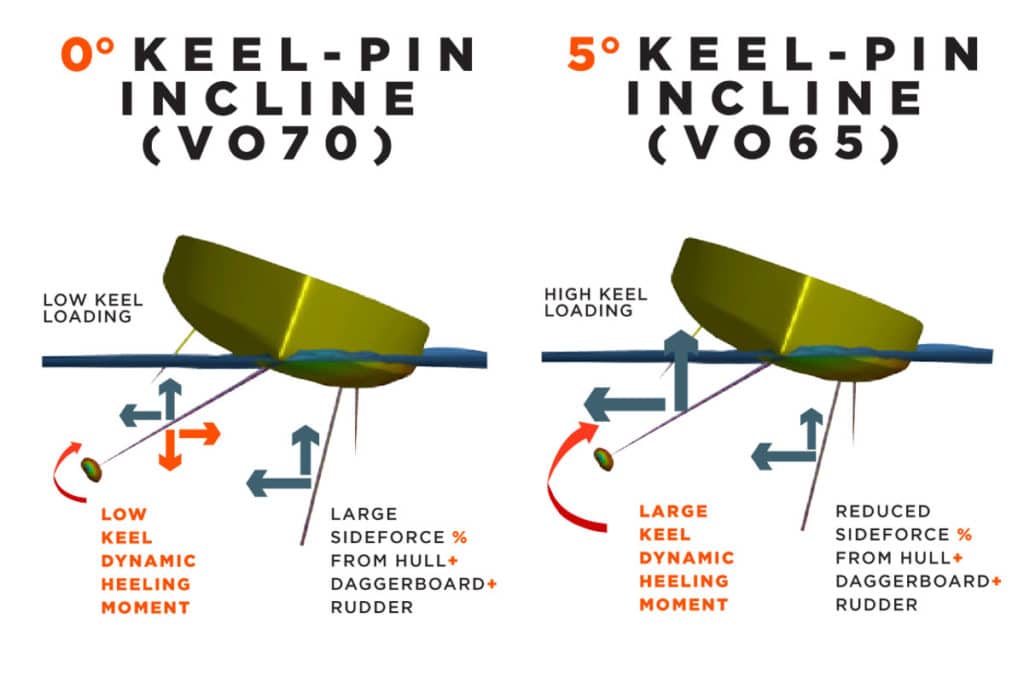

While reduced cost and increased safety was critical, so too was performance for its size, and the ability to break the occasional established speed record. We had to look for relatively inexpensive ways to increase performance with a smaller platform. One way to do this was to increase the keel draft. Another fertile area has to do with the canting keel-pin axis. This is an area of substantial increased performance relative to the VO70. With the 70, the keel pin axis was constrained to lie on the water plane and the center plane. What we have now on the VO65 is an inclined keel pin, angles at 5 degrees (see diagram on p. 60), so when the keel fin is canted it’s actually providing lift for the boat. We have a little bit of a balancing act here because the keel fin is lifting the whole boat out of the water, which reduces drag, but it also reduces the boat’s stability. The teams will have to re-learn their daggerboard settings and their keel use to find the best balance now that this area works so differently.

Another area where we were able to reduce costs was with the sail plan, specifically by reducing the number of sails. One key sail of the VO70, which is no longer part of the VO65 inventory, is the overlapping genoa. The genoa was one of the biggest and hardest sails to stack and move. Removing it from the inventory acts as an equalizer for teams of smaller physical stature. Without that sail however, the total sail plan comes under pressure because of the exposed crossover gap in light air. The VO70s would sail upwind with a VMG up to 14 knots with an overlapping genoa (G1), then change to a non-overlapping jib (J1), and on up through the inventory. Without a G1 we’ve created a potential gap in the upwind inventory, so we’ve responded by increasing the total rig height. The resulting fore-triangle height is the same as the 70, and we now have a J1 that is essentially the same size as the one on the 70. By doing that we’ve added horsepower in the base upwind sail inventory, but we’ve also created a more tender boat that will have to be reefed earlier.

Efficiency on deck With an in-line winch pedestal system and twin companionway hatches, there’s now a clear path for any equipment as it comes out of the boat and moves to the back of the boat before being pulled forward. There’s a lot happening in the central pit area between the hatches. About 50 percent of the control lines come directly from the mast to the central pit, with the other remaining control lines coming from outboard, such as the daggerboards and the adjustable jib leads heading to the outboard pit areas. We grouped the control systems based on where they originate, and then made sure they could be cross-sheeted to anywhere on the boat.

Another important element in the pit area, especially from a promotion point of view, is the camera bump. The camera, and media integration, has been an important part of the design. The area with the camera mounted under the overhang provides enough shelter to conduct live interviews with some spray in the shot while providing protection for the microphone. It also gives an excellent eye level perspective of the crew working through maneuvers.

The cabin on the VO65 extends all the way outboard to the sail stack, which eliminates a gap for water ingress into the cockpit. The cabin’s wedge shape has a peeling effect, which drives that water off the boat. We spent a significant amount of time modeling green-water flow over the boat to provide several levels of safety. If water does enter the cockpit, we’ve created a noticeable return in the cockpit sidewall in front of the runner winch, which will redirect the water flow to protect the helmsman’s feet from being washed out.

The deck layout is fairly conventional for a boat of this type. With the reduced crew numbers, this could have easily been a two-pedestal boat, but the three-pedestal arrangement gives the women’s team an advantage because they have enough crewmembers to fill all of the handles all of the time. We tried to make sure that there were scenarios where they could use everything in a maneuver, whereas the men, with fewer hands, wouldn’t necessarily be able to put hands on every tool. We scripted all of the maneuvers on the deck mock-up as a team to prove this out.

Creating an identity The bow has a noticeably reversed stem shape. A lot of styling attention was concentrated on the bow area because it is the most photographed part of the boat by a huge margin. We were under a lot of pressure to produce a boat that was relevant in its image and instantly recognizable. This is one area where a statement has to be made. The fastest boats in the world are multihulls, and they all have wave-piercing bows. The VO65 obviously can’t be a real wave-piercing boat because of the hull volume it possesses for its length and beam, but we can create the image of that type of boat. We feel the bow profile and cabin do create a very specific identity for the boat. From first glance, it’s easy to see how substantial the boat is with the high freeboard and reverse stem. If you look at the boat, it has the basic form of similar boats, although it’s certainly quite a beamy boat. With these proportions, it gives a very substantial feel for its length. On the foredeck, there are noticeable foot stops. We’ve packaged line runs under these, which will help reduce ankle injuries from the sailors rolling their feet on lines. The stops are structural members. We’ve essentially taken the structure from the inside, put it on the outside, and made it multi-purpose.

Overall the boat has a lot more structure than a VO70. The VO70 rule had a minimum number of bulkheads, combined with panel limitations, which allowed us to produce very light and open boats inside. This was good for freely moving gear but, as we saw in the last race, also produced boats that were prone to structural failures. With the VO65, every part of the boat has been designed much more conservatively. We have more structure, for example, with added longitudinal beams in the bow area and an additional bulkhead in the front of the boat.

The rig is deck-stepped, which improves waterproofing and maintenance procedures, and allows the spar to be transported in more than one type of aircraft. There should also be less potential damage in the case of a dismasting. The fore and aft rigging is similar to what we’ve used in the past, with a backstay and a checkstay, each of which is deflectable. The standing rigging is composite (EC6), which the sailors felt was a conservative choice based on their experience from the last race.

The media desk on a VO70 was a low-level consideration, which usually made for a pretty terrible work environment for the media crewmember. With the VO65 there’s more emphasis on providing a true workable area—the navigator and reporter can share and coordinate use of the shared communication systems. The bench-style seats they use can easily be tacked. The VO65 has 800 kilograms more carbon than the VO70, so to save weight we’ve eliminated the separate generator, which means the teams will charge directly off the main engine. The propulsion system has also been changed to a saildrive unit instead of the more complex and expensive retractable drive system on the VO70. This entire area of the boat has therefore been reduced tremendously in terms of weight and complexity. There is a challenge with the folding propeller however, in that most folding props can be a problem above 25 knots of boatspeed, but we’ve settled on a specific folding three-bladed prop that’s designed to stay closed at very high speeds.

VO70 daggerboards were heavily rule constrained and theoretically could have been a very fertile development area. That said, we’ve made several very conservative decisions on the 65 that culminate in a surprisingly simple result.

Our boards are lifted directly from the mast, which eliminates lifting struts. Mast lifting effectively limits board incline because the boards must point at the mast in order to be lifted efficiently. This results in daggerboards that are nearly perpendicular to the waterplane, which is arguably less than ideal from a performance point of view. The daggerboards are also reversible and fully usable at maximum depth when inverted on the new side in a damage situation. The boards are completely identical so that they can work on both sides, which also means that we only have to stock one type of spare board for the entire fleet.

Team SCA’s Volvo Ocean 65

Volvo Ocean 65 Helm

Volvo Ocean 65 Forecave

Volvo Ocean 65

Volvo Ocean 65 Galley

Volvo Ocean 65 Pedestals

Volvo Ocean 65 Pit

Volvo Ocean 65 Transom

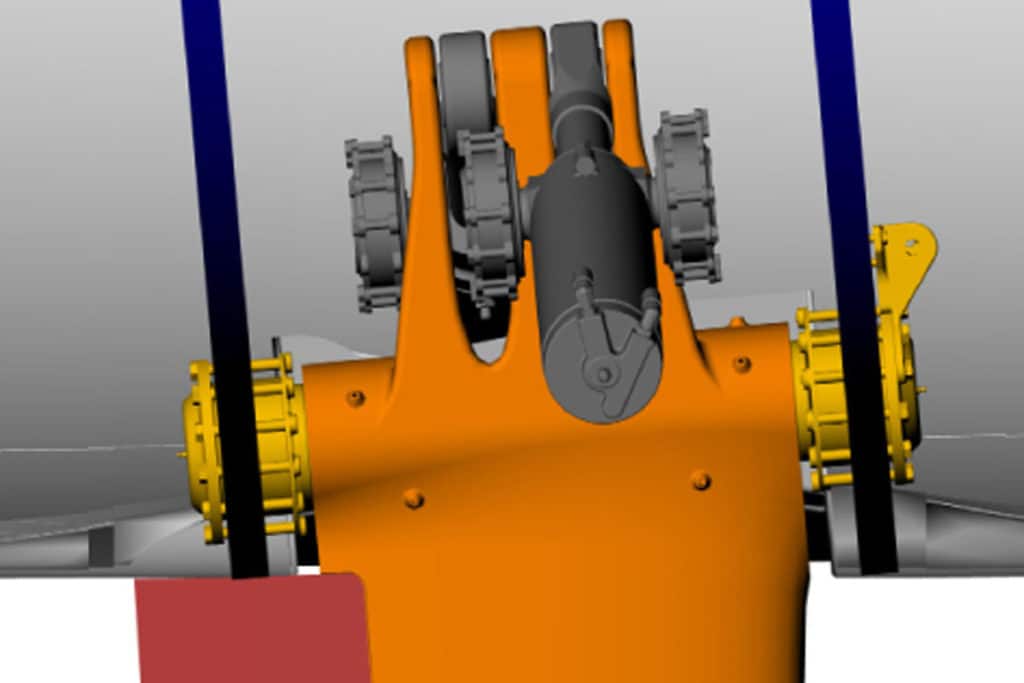

Volvo Ocean 65 Keel-Pin Incline