Ohio might not be the first state that comes to mind when people think about competitive small-sailboat racing, but perhaps a second look is in order, especially when you consider that the Buckeye State is blessed with hundreds of small lakes. There is a popular myth that, other than Lake Erie, there are no other natural lakes in Ohio, and be that as it may, there is an abundance of man-made lakes that date back almost 200 years.

Buckeye Lake, just east of Columbus, was built in the 1820s as a feeder lake for the expanding canal system, and much later boasted great Lightning, Highlander, Interlake and Raven racing fleets. More recently, many lakes were built by the state for recreational purposes, including Acton Lake, near my hometown of Oxford, which has become a hotbed of small-craft racing.

In 1956, the state built an earthen dam on the tiny Four-Mile Creek and formed Acton Lake in what is now Hueston Woods State Park. At 625 acres, it is just shy of 1 square mile—a puddle by any definition. In its wisdom, the state initially placed a low-horsepower restriction on powerboats, and this no-wake environment was perfect for canoeing, fishing and small-boat sailing.

At first, there was no organized sailboat racing, but eventually the Hueston Sailing Association was formed to encourage sailing and racing almost as soon as the lake filled. Because the lake is situated in a state park, the HSA had no property other than a small pontoon race-committee boat, and an even smaller crash boat. However, the park did give the HSA use of a bulletin board and let them set up a tent near the docks on race days for postrace scoring and protest hearings. Boats were kept in sturdy wood slips or on trailers and sailed out of dry sailing lots. Like most Midwest lakes, the water was silty, and unless you had a hoist or dry-sailed, hulls needed to be cleaned weekly to maintain a fast bottom.

I was 13 years old when Acton Lake opened to the public. I knew nothing about sailing, so I naturally lobbied my parents to buy a powerboat. Instead, my father got a friend to take me sailing on his 16-foot fiberglass Rebel-class one-design sloop, a Ray Greene design reputed to be the first fiberglass production sailboat class. The Rebel wasn’t exactly a speedster, but I caught the sailing bug, and the following summer, another friend loaned us a 14-foot sloop-rigged no-name scow that had been built out of plywood from plans in Popular Mechanics. It was heavy and slow but amazingly stable, and it fell apart at about the same rate that I learned how to repair it. I read a few how-to-sail books, learned the basics by trial and error, joined the HSA, and started racing it in their Sunday races.

By the late 1950s, the HSA had established fleets of Thistles, Rebels, s, Y-Flyers, Snipes, Rhodes Bantams, and a large handicap fleet of all manner of small sailboats, including Penguins, Sailfish, Windmills, and off-brand boats like my no-name scow. Sunday-afternoon racing was simple: a single start with all the boats starting at once and one long race, several times around a short course. These starts often had 25-plus boats of different sizes and speeds starting at the same time—great training for learning how to start in big fleets.

Courses could be a problem. The lake was longest on its north/south axis, but the wind was more often out of the west, and with a west wind, it was almost impossible to get long enough windward legs. The answer was a figure-eight-shaped course with two windward marks set far apart on the west shore—one taken to port and the other to starboard—and two corresponding leeward marks. The reaches had all the boats crossing at the center of the course in demolition-derby fashion, and we all had to learn right-of-way rules quickly to avoid collisions, like the time a Y-Flyer on a full plane T-boned a Thistle amidships.

The reaches had all the boats crossing at the center of the course in demolition-derby fashion, and we all had to learn right-of-way rules quickly to avoid collisions, like the time a Y-Flyer on a full plane T-boned a Thistle amidships.

To add to the challenge, the wind was often light and almost always shifty. Sailors had to concentrate on the shifts and learn how to maintain boatspeed and optimal track in the variable wind conditions. Because of the size of the lake, you never sailed very long on one leg, so crews got a lot of practice in tacking and jibing in close proximity with the other boats on the course. Every race was a learning opportunity, and if you paid attention, you could learn more in an afternoon on Acton Lake than a month of sailing on a larger lake with steadier winds.

After a few seasons of racing my no-name scow, I wanted to race a one-design and went halfsies with my family to buy Rhodes Bantam No. 836, a wood boat from the Gibbs Boat Company in Michigan. There were a couple of talented racers in the small fleet. I paid close attention to what they were doing, and in time, I started winning my share of races. In my first away Bantam regatta on Lake Erie, I marveled at how easy it was to sail in steady wind on a large body of water, but the skills I had learned on Acton Lake gave me a real edge when lake conditions turned light and shifty.

There was also another good Rhodes Bantam fleet on nearby Cowan Lake, a somewhat larger puddle near Wilmington, Ohio, and by the 1960s, we were having great home-and-home regattas—the Feather Duster and Arby Darby (get it? “R-B” Darby). The quality of the racing was impressive, and soon these regattas began to draw Bantams from all over the Midwest. The R-B Class even held its International Championship regatta on Acton Lake in 1971. I was in the US Air Force in nearby Dayton at the time, but the Air Force sent me to Texas for a four-month temporary-duty assignment and I missed the regatta. Years later, my son and I went on to win the Rhodes Bantam Internationals, and I credit years of puddle racing for helping me learn how to race in a variety of conditions.

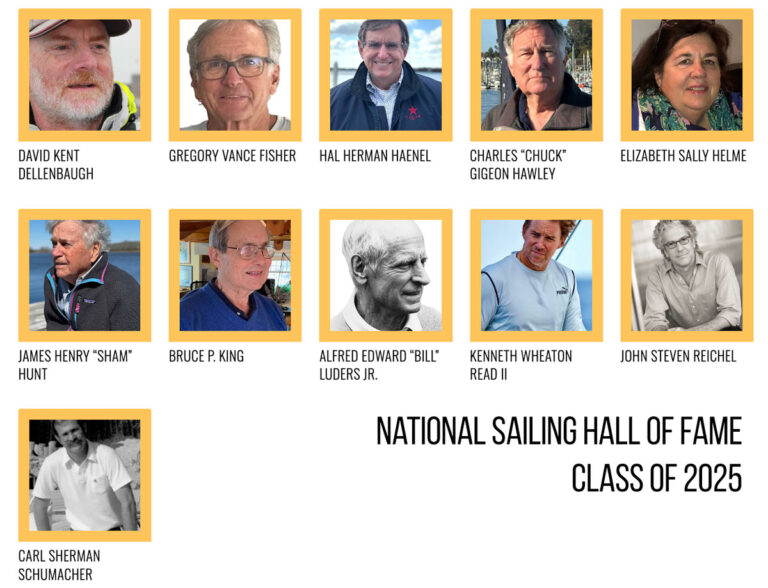

I wasn’t the only Acton Lake puddle racer who enjoyed some success. By my recollection, at least two other HSA one-design skippers went on to win national championships in the Y-Flyer and Rebel classes. Other Ohio puddles (Cowan Lake, Buckeye Lake and Hoover Reservoir, to name a few) also produced their share of small-boat champions. Buckeye had a world-class Lightning fleet in the 1960s and ’70s, and I crewed there often when I was in college. The Fisher family (George and sons Matt and Greg) were always hard to beat, and all of the Fishers went on to win an impressive number of regional and national championships.

To illustrate the level of passion that this tiny lake generated, one of the HSA racers, Dr. Jim Wagner, a Y-Flyer skipper, took the specs of the popular Y-Flyer scow and scaled it down to a three-quarter version that he dubbed the W-Scow. It could be sailed singlehanded or doublehanded, and several were built by HSA members just for fun and to help younger racers make the transition to the full-size one-designs. Another member built a beautiful wooden International 505 but added a full 4 feet to the length of the mast, with a dramatic increase in sail area. She was a handful in a breeze but almost unbeatable in light air.

Puddle racing is similar to frostbiting. The courses tend to be short, with lots of mark roundings and tactical situations. Beats are a challenge in the crowded and shifty conditions, and short reaches and runs place an emphasis on developing boatspeed quickly, quick spinnaker sets and douses, and good offwind tactics. Boats seldom get too spread out, and a good knowledge of the rules is crucial when sailing in the resulting traffic. Concentration and paying attention to windshifts and the competition are usually more important than flat-out boatspeed.

In my mind, “puddle” was never a pejorative descriptor. It just meant that you were yacht racing on a small patch of water with good friends, all of whom were hell bent on getting a good start and beating you to the first mark. Sometimes good things do come in small packages.

Editor’s Note: We all have our favorite hometown regatta, whether it’s the annual big-fleet jamboree or the locals-only intergalactic championship. Maybe it’s the season opener or the midsummer rally with a start and a finish at the grill. It could be our seasonal offshore passage, the club charity race, a sprint around some quirky geographical fixture, or simply the best harbor, pond or puddle regatta that no one else has ever heard of. We know that these local favorites are happening everywhere and every day around the sailing world, and we’d like to share them through this column series. If you have a favorite to share, drop me a tip at dave.reed@sailingworld.com.