Once they have reached the Southern Ocean, the solo sailors have to deal with a series of low-pressure systems for a month or more. From the islands of Tristan da Cunha and Gough to Cape Horn, they have around 12,000 miles to sail along the wall of ice marking the limit of the ice drifting up from the Antarctic. This is the toughest part in the rough seas of the Indian Ocean and the long Pacific swell. Once out of the grip of the Southern Ocean, they still have 7,000 miles left to sail up the coast of South America and then in the North Atlantic before they see the South Nouch Buoy marking the finishing line of the Vendée Globe.

In the space of barely one month, the competitors go from the cold Vendée weather to the torrid heat of the equator, tropical downpours and then back into the icy conditions of the Antarctic. The Southern Ocean represents nearly 3/5th of the round the world voyage with a series of low-pressure systems rolling out of Brazil, Madagascar and New Zealand… It is this succession of downwind conditions that the sailors try to stick with, gliding from one system to another without getting swallowed up by the tentacles stretching out from the highs. From strong northwesterly winds, severe westerly squalls as the front passes over, then a shift to an icy southwesterly, these changes are very demanding for the solo sailors and their boats.

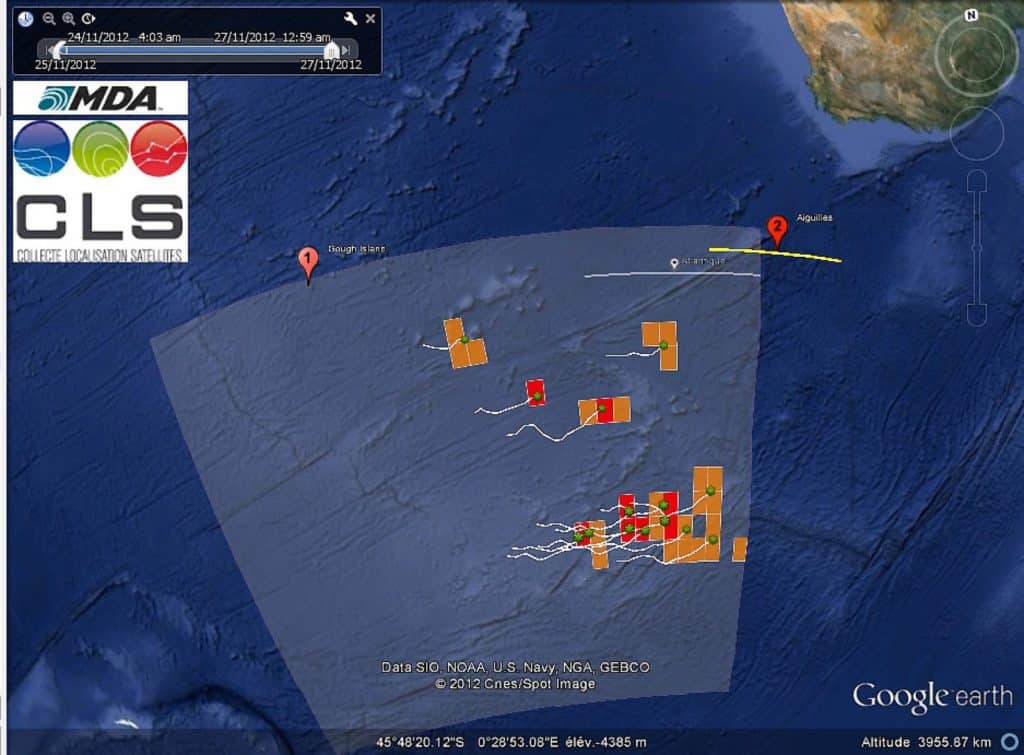

Today, icebergs are now avoided by the Race Directors, who have set up an ice exclusion zone around the Antarctic between 45°S near the Crozet islands and 68°S off Cape Horn. This zone implies a higher route flirting with the Mascarenes High (Indian Ocean) and Easter Island (Pacific Ocean). Whilst there have never been any winning comebacks in the Southern Ocean in the seven previous editions, that may well change in this year’s southern summer, as the leader(s) could get stuck in a ridge of high pressure, while those chasing them could be taking advantage of a low-pressure system.

The long way home

If rounding the Horn after more than fifty days at sea marks a huge drop in the levels of stress due to the lower risk of damage and the rise in temperature, the 7,000 miles that remain before returning to Les Sables d’Olonne are not that easy, particularly if other competitors manage to claw their way back into contention. Once they have Patagonia in their wake, they have once again to get around the St. Helena high and deal with the stormy areas of low pressure pouring out of Brazil, which is synonymous with strong and variable headwinds, huge wind shifts and fronts to deal with. In other words, this is no easy task.

Then, they have the Brazilian coast more or less within sight before the Doldrums appear over the horizon. Here, they pass to the west of Fernando de Noronha, before picking up the easterly winds associated with the Azores High. This area of high pressure can sometimes stretch out to the Caribbean, split into two areas, which move around, or shrink back to Europe. In any case, the sailors have to avoid getting stuck in the calms before they finally get to the Atlantic lows, which in January can be even more horrendous than what they witnessed in the Southern Ocean. At last, after between 75 and 80 days at sea, the winner of the 2016 Vendée Globe will finally be able to make out the South Nouch buoy marking the finishing line of the Vendée Globe off Les Sables d’Olonne.

The voyage should chiefly be sailed downwind, but for the first time in this eighth edition, there may be a rather different situation in the Southern Ocean, if the Indian and Pacific highs decide to block the solo sailors’ passage as they contend with the exclusion zone set up to avoid the ice from the Antarctic. To win, first you have to make it all the way around.