When you watch an IMOCA 60 sailing, in most cases, you can only see two sails being used at the same time, in general, the mainsail and headsail. In fact, they have nine sails available on board and they must combine these depending on the strength and direction of the wind and the sea conditions. The sails that are not in use are stowed for stacking. In other words, they are moved from one side of the boat to the other by the skipper to balance the boat (we are looking at several hundred kilos) and enhance performance.

For amateur sailors, nine may seem a lot, but for Vendée Globe racers, it is not that many, as Yann Eliès explains, “In previous editions, we have been able to take thirteen with us. But the way our sport has evolved means we take fewer and fewer. For two reasons. Firstly, because today we are able to manufacture sails which are better all round performers with a wider range of use… and secondly, we have to bear in mind the cost. Sails are very expensive and we are always on the lookout for ways to cut our budget, so this was the road to go down.”

Two must have sails: the mainsail and the J2

Yann Eliès explains, “If we take things to extremes, we only need two sails, the mainsail and the J2. These are sails we must have on board and ones we use very, very often.”

The mainsail

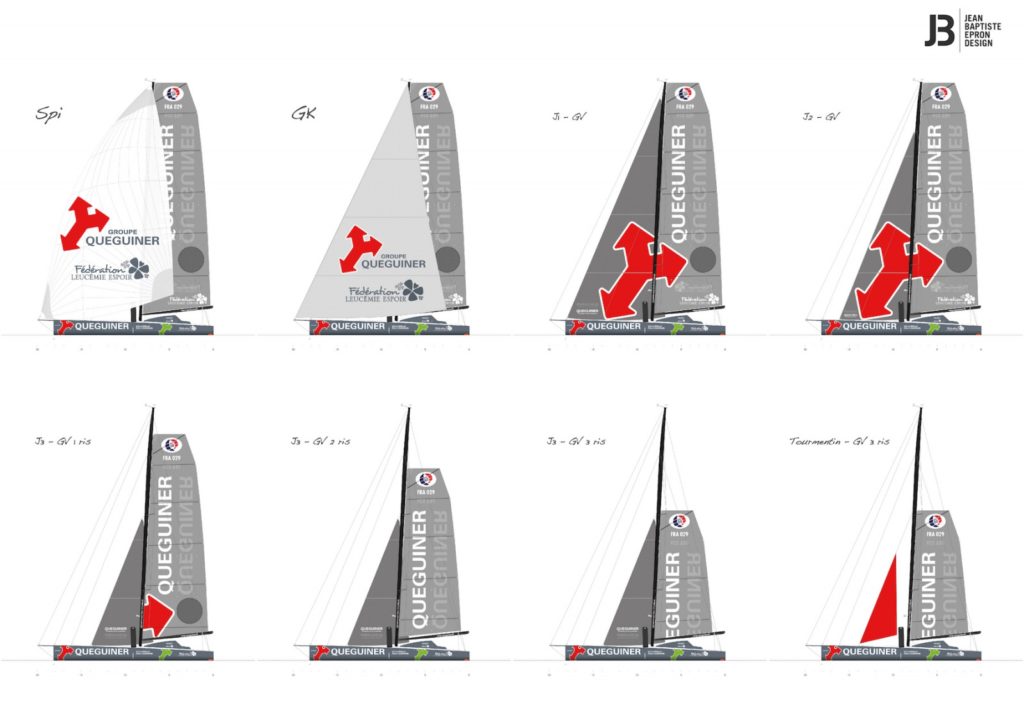

This is the best known sail, which is positioned furthest back, attached to the boom and the back of the mast and which towers almost 30 m up. Unless there is a major incident, it remains in place throughout the Vendée Globe and (to put it simply and leaving to one side checks or incidents) it is hoisted on leaving the harbour entrance channel and only brought down against the finish 80 days later. In use practically all of the time, the mainsail offers the essential property of being reduced depending on the strength of the wind, which involves taking in a reef or shaking one out, by lowering the sail on the mast, which automatically reduces the length of the edge along the boom. Its surface comes to 280 square metres when under full sail on Groupe Quéguiner. But contrary to what the name suggests, it is not the biggest sail on board, as the spinnaker and big gennaker have a larger surface. Yann Eliès: “There are four positions for the mainsail and so 4 different surface areas: full mainsail, 1 reef, 2 reefs and 3 reefs. Some racers even have a fourth reef, where only the top remains up.” Depending on the strength of the wind and the combination that is chosen with the headsail, they sail either with the whole surface or between one and three or four reefs.

J2

J is quite simply used to refer to the jib or the genoa sails. The numbers correspond to the attachment points on the stays, which are positioned closer or further away from the stern of the boat. These cables joining the mast to the deck, some of which can be moved, enable the headsails to be set. Number 1 is on the bow of the boat (but not on the bow sprit, to which only the big downwind sails are attached: spinnaker and gennaker). Number 2 is slightly further back on the deck and number 3 quite some way back close to the mast, when smaller sails are required.

Let’s begin with the J2, as this is the second required sail on an IMOCA. Yann Eliès: “We must have a fixed mainstay and this must remain in place. The J2 is the sail that is attached to the main cable and is fitted to a furler. This is the only headsail with battens. It is in place at all times. This is a rather flat sail with a wide range of uses from 45 to 110/120 degrees to the wind, and sometimes even downwind in strong conditions. The J2 measures around 100 square metres.” This is a vital sail that we really have to look after, and for example we sometimes use a reacher in its place (see below – the ninth sail).

The spinnaker

The spinnaker is the big balloon sail for use with the wind from astern. This huge sail is the biggest on board measuring 400 square metres. The equivalent of the surface of a basketball court. This is an asymmetrical spinnaker, so has no pole. Yann Eliès: “We still all take a spinnaker aboard, even if we have tried to get rid of it, as the use of this huge sail is tricky when you are sailing alone, particularly as it is the only sail that doesn’t get rolled up. Maybe the foilers will be able to do without it one day. We’ve been trying to do without it now for eight years, but for the moment, we still need it. We use it with the wind from astern from 5 to 25 knots when sailing double-handed. When sailing solo, we tend to bring it down sooner, before the wind reaches 25 knots. The spinnaker is attached to the bowsprit.”

The big gennaker

The big gennaker is indeed big too: 300 square metres. “Attached to a furler, this big sail is used in similar conditions to the spinnaker. I use it between 15 and 30 knots, at between 120 and 160 degrees to the wind. Below 15 knots, the spinnaker is a little bit more efficient. But let’s say that the big gennaker can sometimes replace the spinnaker, if the latter is ripped or lost. This is a big downwind sail that we can use while the wind is below 30 knots.” 30 knots is more than 55 km/h for landlubbers…

The small gennaker

The small gennaker – 200 square metres – is used when sailing downwind when the wind is stronger still. But this sail has a dual function, as Yann explains: “The mall gennaker is also attached to the bow sprit, but on top it is attached to a halyard just a few metres from the mast head, just above the J2. This is a sail for strong downwind sailing, when there is between 25 and 35 knots of wind. But this sail also has another function: it can be used as a code zero when luffing up (sailing close to the wind) in lighter airs. In the past we had the code zero for that. The advantage of limiting the number of sails is that we are starting to see dual use sails.”

The J1 or Solent

The J1 is attached to the biggest stay, which goes from the bow to the mast head. It’s a flat sail that we might imagine was uniquely suited to sailing close to the wind. But in reality, because of its relatively large size – 140 square metres – it can do much more. Yann Eliès: “To put it simply, the J1 is good close to the wind, when the wind is between 10 and 15 knots or so, but we tend to use it too by making it less flat when we are further away from the wind. As the J1 is a big sail, it has a wide range of use: it can go up to 120 or even 130 degrees to the wind.” The J3 , or staysail or ORC jib

The J3 is on the shortest stay, the one furthest back on the bow section. So logically it is the smallest (50 square metres). Yann Eliès: “Initially, this was a sail for storms and sailing upwind, the final sail to be used in heavy weather. But more importantly, it is an al round sail, as it can be used in combination with another headsail (meaning the boat may have three sails up at one time, the mainsail and two headsails). With the J2, it is the sail that is most often in place on the deck or up in the air. We hoist the J3 when the wind gets above ten knots, from 90 degrees to 160 degrees to the wind, as well as being used downwind. It can be combined with all of the sails. We often use the combination J1 + J3, or the small or big Gennaker + J3, for example. It stabilises the boat and helps direct the flow of air towards the mainsail. It is also very useful in masking another sail that we are trying to furl and acts as a screen. A few years ago, the staysail, was only used when sailing close hauled in strong winds. It is now not as flat and has more uses with its range increasing all the time. In the Volvo Ocean Race, it was used very often. It’s a sail that doesn’t harm the others in any case, so we tend to leave it in place.”

The storm sail

Let’s move onto the eighth sail, which is fluorescent orange, as it is very small and you’ll probably never see it hoisted. Yann Eliès tells us why: “It’s the compulsory sail for use in storms to comply with international law. We hoist it every four years to check it in the Fastnet Race, then it goes back in its bag and stays there. Even in a huge storm, aboard these boats, we prefer to sail with reefs in the mainsail or without a mainsail and just the J3. The storm sail is something we just carry around with us in its bag.”

The ninth sail: the secret weapon?

A lot has been said about this ninth sail. It was Michel Desjoyeaux’s magic staysail and then the lethal weapon or winning reacher for François Gabart. Sailors, who are not limited in terms of the materials or size of sails have choice to make with the ninth sail, which can be a major asset. Its surface is close to 115 square metres. “It’s always our secret sail,” smiled Yann Eliès, “the one that raises questions: would it be better to take a Code zero or a sail for use in stronger winds, for example? This sail has become somewhat redundant with the indispensable J2, but it is better suited to downwind breezes, so in the Southern Ocean. It is attached to the bow and hoisted to the hounds rather than the top of the mast. Very resistant, we’ll be using it practically all the time in the Indian and Pacific. On top of that, it has another very important function. It means you can save the J2… which is required for sailing back up the Atlantic, once you have rounded the Horn.”

Extra info

The secret weapon? “We’re not necessarily looking for the magic sail,” said Yann Eliès, “but the goal is to get sails that are useful in as many situations as possible, so that we don’t have to carry out as many manoeuvres. In the Southern Ocean, if conditions are difficult, it is better to avoid manoeuvres out on the foredeck as much as we can and we can sail with three or even four sails up.”

Sail changes require a lot of energy from the sailor and can be costly in terms of the ground lost, when you are sometimes forced to sail for several miles in the wrong direction to make the change, added Yann. That’s “why it is important to get it right” and see whether it is worth it. In a Vendée Globe race, a change in sail configuration means you stick with that for at least 4 or 6 hours to profit from the change. If you just have to furl or unfurl the sail, you can carry out that change in a two hour period.”

The latest materials developed in particular by North and Incidences Sails, which are very popular with Vendée Globe skippers, mean that it is possible to have relatively light sails, which are solid and keep their shape. They can easily be spotted, even at sea.

A sail change on a 60-foot IMOCA is not as simple as that on a dinghy or family cruiser. Each of the headsails weighs between 50 and 70 kg, and sometimes around 100 kilos with all the extras. “A sail is also a halyard, sheets, furler, hook, etc” Yann Eliès explained. They often have to taken outside and down below to balance the weight, which sailors refer to as stacking, which is very, very physical.

Even fewer sails in the future? “That is the trend and it is possible. I think we can go further, for example by limiting the number of sails to six, as in the Figaro races.”

The future? “There have already been attempts to make a wing that can be reefed in. It’s too early to see that happen in the Vendée Globe, but with the foils and higher speeds with the creation of an apparent wind (*), the natural direction we are going in with equal or better performance levels is to have sails that are smaller and smaller, flat and twisted that are closer together with mainsail tracks that are narrower and narrower.”