You won’t get better or win races if you tell yourself you suck at sailing. Or life. Or work. Or while advancing the sport to a better place.

This is the wisdom of professional snowboarder Kevin Pearce, the morning’s keynote speaker on the fourth and final day of the 2023 Sailing Leadership Forum. The topic at this particular moment in his talk is about negativity and how it’s a barrier to one’s personal fulfillment.

Pearce speaks with authority because he has battled his own demons of negativity—from the moment his head slammed into the icy transition of a halfpipe built to launch him to the Vancouver Olympics. The horrific accident, and the traumatic brain injury that resulted, halted his gold-medal quest and detoured him on a long but inspirational journey of recovery. “Focus on the positive” is the point he’s hammering home to the forum audience. There are real chemicals in your brain at work when you do. Trust him. He knows the science.

Earlier, Pearce had posed a simple question after he stepped onto the stage: Why would a snowboarder be at a sailing conference? To inspire, of course. That’s what good keynoters do, but the real answer would eventually come when he closes with a few important takeaways: Use your brain for good, personally and professionally. Love what you do. Focus on the positive. Pass along the stoke.

And that’s exactly what’s happening across the sprawling conference center—on the beach, in the breakout rooms, at the cocktail parties, the award ceremonies and the afterhours. For anyone in the business of shaping sailing’s future, the biennial gathering is the place to be. This year, in early February, nearly 600 attendees hunker down and get elbow to elbow doing the good work for every level of the sport. Growing it. Promoting it. And living it. In the next seat are officers of yacht clubs big and small, sailing schools new and old, and community sailing centers growing faster than they can manage or afford. There are young and senior race officials, coaches and instructors shop-talking, recruiting, and doing recon for the next great solution. It’s four days of learning from each other—immersive enough to make your brain hurt, but that’s what the cocktail hours are for.

From the thick fog of a forum week, however, clarity does eventually come once you sit back and take stock of it all. At this forum in particular, there was a real sense of urgency and excitement. Sailing is on fire, and while each of us are immersed in our own little corner of the sport, it’s easy to miss all the hustle that’s happening across our waterfronts.

The sport is not dying. It’s diversifying—rapidly. That’s a positive for the future of wind-powered sports. It’s a great time to be a sailing kid. I admit I used to gripe about modern-day junior sailing. It was jealousy, really, of all the coddled kids with parents toting them and their coaches around the country and abroad. Skiffs, kites, windsurfers, wings and foils—come on, now. That’s not fair. Youth sailors not only have all the fun boats today, but they also have what you and I did not: professionally organized pathways to anywhere a kid wants to go in sailing and beyond.

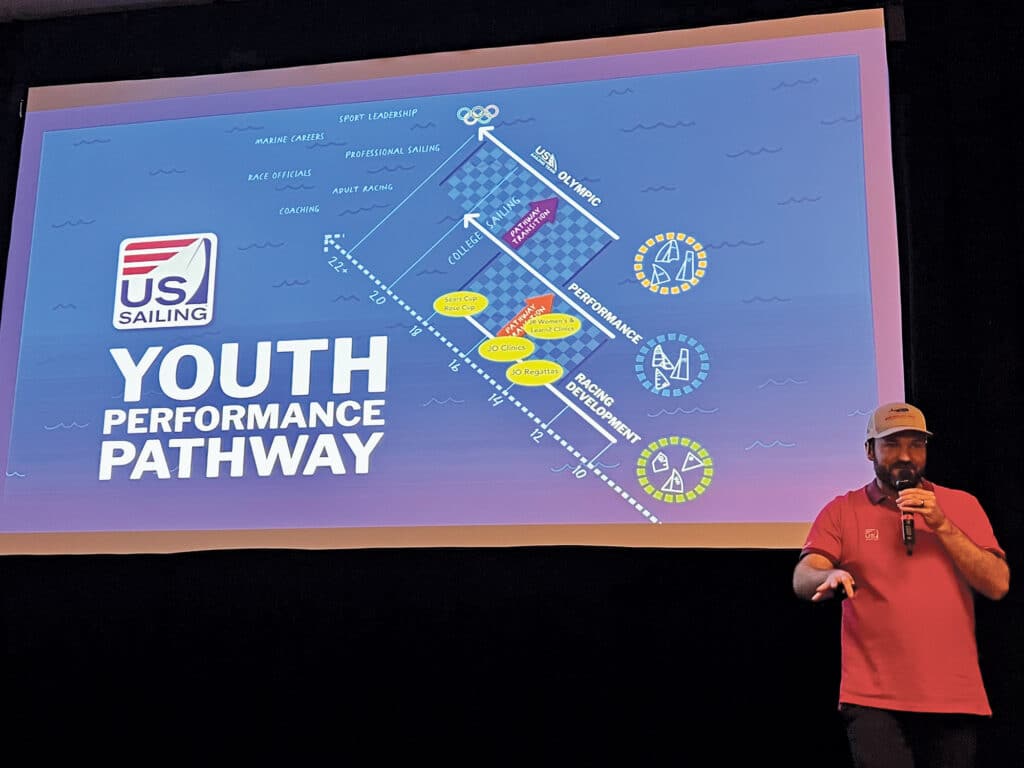

Making lifelong sailors is the goal, says John Pearce, US Sailing’s youth competition manager, who leads a session at the forum entitled “Youth Racing Pathways.” He makes a darn good case for the modern-day performance-racing paths. His flow chart maps out the many ways to progress: Start the kids in Optis or whatever boat you have until they’re 14 or so. Then for the next four years, take them up a notch to the ILCA 6, Nacra 15 or 29er. Those who don’t take to the dinghy pathway can advance to small keelboats and aim for the Sears Cup—the granddaddy of all youth trophies. From age 16 to 20, it’s college sailing or a committed tack to the Olympic on-ramp. And if all goes to the Pathway plan, the end of the road is pro sailing, marine careers, coaching, adult racing, race officials and tomorrow’s leaders.

The flow is not always fixed or perfectly linear, however, and we know only a select few will sail to the tip of the spear. And that’s OK. Pearce’s co-presenter at the breakout session, Maxwell Plarr, director of sailing at Virginia’s Hampton YC, says he has no interest in fueling directly into the Olympic pipeline. He’s happy to let those eager birds fly from his nest early, but his focus is keeping it fun. Over the past few years, he’s led a few junior-boat experiments with the support of the club’s board of directors, and the results were surprising.

International 420s? Nah. The kids didn’t go for it. 29ers? Now, that they are into, but it takes a more careful approach to skill development. How about adding a couple of wingfoil setups to the quiver? Oh yes, they did.

“If you don’t have a wing in your program,” Plarr tells forum attendees, “get one.”

Hampton’s youth sailing program is healthy, he says, and it’s producing top-level keelboat kids too, but he’s not doing it alone. He’s constantly leaning on the resources at US Sailing, which he says makes his life a lot easier. He’s got Pearce on speed dial. And that’s cool, says Pearce, because that’s what he’s there for. It’s his, and US Sailing’s, responsibility to support every organization.

How US Sailing attempts to serve so many masters is a complicated story for another day and place. The organization is not perfect, but it’s trying. And it wants all of us to be part of the progress. Membership revenues are a significant source of income that trickles out to the sailing community. Benefactors and corporate partners are essential too. There are many mouths to feed, but if there’s one thing US Sailing want us all to know, it’s that it’s bent on serving everyone, which is, of course, easier said than done.

Of the estimated millions of sailors in America, only a tiny fraction are dues-paying members, and I suspect you and I know many in our own circles who are not members either. Reasons run the gamut, but the most common is: “There’s nothing in it for me.”

Be that as it may, those among us who sit on their hands and complain about a lack of available crew, bad race management, unfair ratings, high entry fees and the like have no skin in the game. Kevin Pearce would say: Don’t complain if you don’t belong, and take your negativity elsewhere. It’s not helping.

Belonging goes beyond “what we get” for the $79 individual membership fee. Sure, we get the digital rulebook and partner discounts that will save us the same amount. But it’s not the money that’s important; it’s each of us doing our part to advance the sport to a better place for those who follow. It allows US Sailing to invest in retaining those who walk through the doors of community sailing centers, yacht clubs and sailing schools—organizations that need certified instructors and educational programming. Think of it as a down payment on your future crew pool.

US Sailing is committed to improving the capabilities of the important offshore office too, which was understaffed and underfunded for far too long. Here, Jim Teeters, head of the Offshore Ratings Office, is getting the house back in order. At Teeters’ forum breakout session with Stan Honey—the smartest guy in sailing—they reveal they’re working on a tweak to handicap scoring methodology that Honey is certain will create better races, as well as happier owners and tacticians. Applying modern weather forecasting technology, he says, will make handicap racing “more fair and less complex.”

Like Pearce and his Youth Racing Pathway, Teeters and Honey also have a flow chart to explain this novel concept of a “forecast time correction factor.” With the FTCF, Honey explains, sailors will more accurately know their time allowance before the race starts, so they can make better tactical decisions during the race. The forecast part of the FTCF is done by predicting the wind before the race starts using the highest-possible-resolution weather file. In essence, a race committee would estimate the course, enter the polar file for each entered boat, route each boat around the course using Expedition software or a web-based application (to be developed), and deliver “time correction factors” to competitors shortly before the race starts.

This is the sort of stuff we learn at the forum, from two of the most intelligent guys in the handicapping space. They’re committed to achieving a better race outcome for you and me, and I argue that this alone is worth a slice of the membership. We can’t complain about our rating or the quality of the outcome if we don’t invest in the game, and that applies to both skippers and crews. Yes, if you’re on the rail and calling the shots, it’s to your benefit as well.

One might say that four days neck-deep in US Sailing has me gulping the organization’s Kool-Aid, but that’s not the case. All we have to do is sit and listen—with a positive mindset—to the many people out there advancing the sport on our behalf. Sailing is on fire because of them, and it’s on all of us to help fan the flames.

Take, for example, Jessica Koenig, the outgoing executive director of Charleston Community Sailing (South Carolina), who collects the Martin A. Luray Award at the forum’s Community Sailing Awards Luncheon on the final day. Koenig closes the gathering by sharing that she introduced more than 16,000 people to the sport in her time at the sailing center, and “that feels pretty special.”

Charleston Community Sailing is but one of many organizations across the country that rely on US Sailing for support in some way, and I have no doubt Kevin Pearce would agree that they’re all winning because of it. When it comes to shaping the future of our sport, they’re making a positive impact, and they certainly don’t suck.