It may never happen again.

What we’re talking about is The Ocean Race’s monster of a stage through the southern Indian and Pacific. What was originally a solution to the impossible challenge of trying to organize a round-the-world race with stops through Asia in the time of COVID-19 may have manifested itself as a new classic course—the new Everest peak for fully crewed ocean-racing teams, starting in Africa and ending in South America.

It was always going to be one hell of a challenge, this great distorting marathon sitting among six other standard-size Atlantic-based stages in the 50th anniversary edition of The Ocean Race, formerly the Volvo Ocean Race and the Whitbread. And it looked to have disaster written all over it because there were so many unknowns: Would the foil-assisted IMOCA 60s, with their delicate appendages and lightweight hulls, be able to cope with the violence of being pushed full-pelt for 35 days through the most inhospitable seas on the planet? How would their four-strong sailing crews survive in their spaceship-size capsules, on a platform with a ride quality ranging from uncomfortable to unbearable? And how would the race’s credibility survive this challenge, with only five boats on the starting line under Cape Town’s Table Mountain? What if three—or worse, none of them—failed to complete the course? This later concern weighed heavily on race organizers and fans alike.

In the end, we were treated to an epic sporting story too deep and expansive for this space. And it was one that proved that even if there were only four boats on the racecourse (Guyot Environnement-Team Europe dropped out with structural issues), if they are good boats, then it can be a compelling watch. And these were good boats sailed by some of the world’s best solo and fully crewed yachtsmen and -women.

Leg 3 had everything: big downwind racing in towering seas and storm-force winds, and long periods of atypical calm for the Southern Ocean, even in summer, and remarkably close racing. How close? While passing the most remote spot in the world’s oceans at Point Nemo, all four boats were within hailing range of each other. And there was some serious record-breaking pace at times, with the IMOCA 24-hour distance record smashed, jumping from 539 miles to 595 miles, courtesy of Kevin Escoffier and his crew on the Swiss-flagged Holcim-PRB.

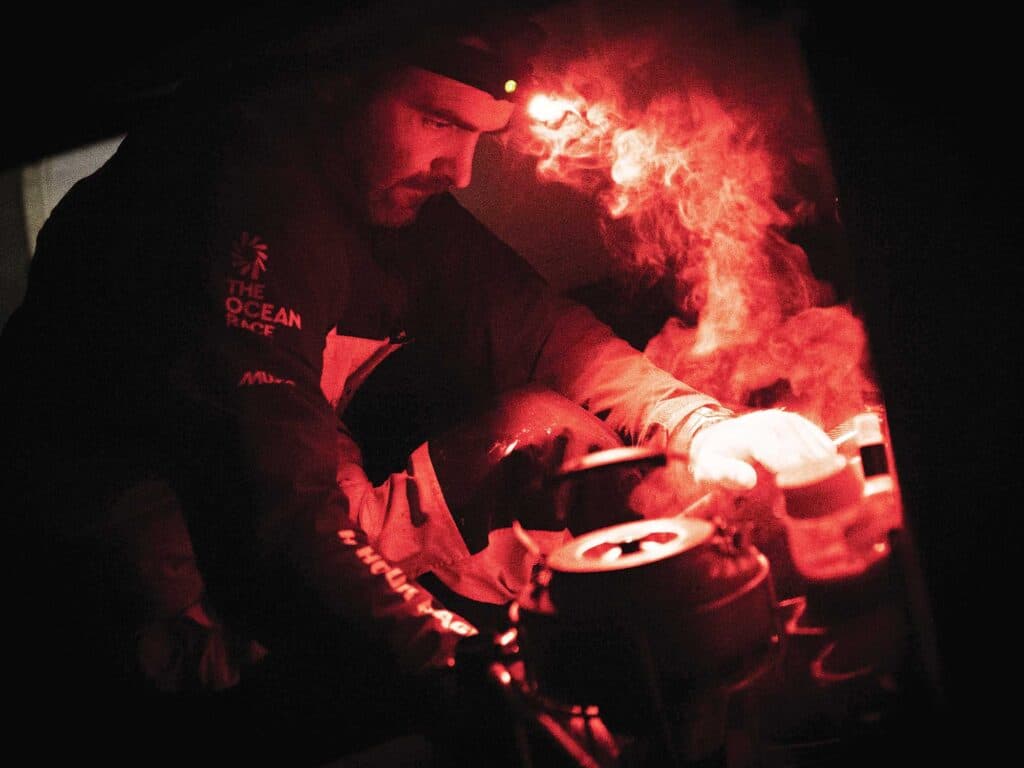

The leg captivated a hungry social media audience with compelling stories of resilience, determination and resourcefulness by each and every crew as they battled rig and sail damage, hull and appendage structural failure, and personal injury in one case to keep their race on course. And all of it was vividly recorded and shared by the onboard reporters (OBRs) forbidden from taking part in crew work. What the OBRs gave us was a fascinating Big Brother’s-eye view of everything that went on for over more than a month at sea, plus compiling some of the most spectacular drone footage of foiling yachts in the Big South, the likes of which had never been captured in such high definition.

Of all the subplots that played out over 36 days, the most compelling was that of the eventual leg winner—and a surprise winner at that: Team Malizia, skippered by the charismatic German Boris Herrmann. Alongside him was the young British sailor Will Harris, the experienced French navigator Nico Lunven and the Dutch sailor Rosalin Kuiper. The team’s 2020-vintage VPLP-designed boat was tipped by many to come last in this race because it is big, heavy, and slow to get up on its foils in marginal conditions. Indeed, in Leg 2, from the Cape Verde islands to Cape Town, Malizia lost 200 miles to the fleet in just three days.

On Leg 3’s long eastbound highway, however, the hope for Herrmann and his crew was that their beast of an IMOCA would show its true pedigree in the South, and so it proved. But long before it could do that, their race almost came to an end after three days when the Code Zero halyard lock failed and the halyard carved a 30-centimeter trench in the front of the mast, 90 feet above deck.

At this point, the temptation to return to Cape Town was almost overwhelming, but the crew decided to try to repair it. “We thought about going back to Cape Town. That would be an easy reaction. But now we have all agreed to try and continue—it takes even more mental strength to do this than such an endeavor takes anyhow. The day we stand on the dockside in Itajai, I will be super proud,” Herrmann said at the time.

Little did he know.

With Harris and Kuiper taking turns at the top of the rig, they managed to complete a decent patch-up of the spar during a light spot in the weather and got their race back on track, albeit more than 300 miles behind the early leader, Holcim-PRB. The Swiss boat would extend its advantage to more than 600 miles before being reined back in—such is the nature of ocean racing, where being too far ahead can be a curse.

Alongside the US entry and pre-race favorite, 11th Hour Racing Team Mãlama skippered by Charlie Enright, and the French-flagged Biotherm skippered by Paul Meilhat, the game was now all about hunting Holcim down by diving south toward the ice exclusion zone, looking for stronger winds.

If times were tough on Malizia, they were arguably even worse on Mãlama, where Enright and his team, which included veteran British navigator Simon Fisher, British-Australian sailor Jack Bouttell and Swiss soloist Justine Mettraux, were contending with cracks in both their rudders. They repaired one and swapped the other for the spare and crossed their fingers.

The first goal for everyone was the midleg scoring gate under southeastern Australia, where Holcim added to its wins in Legs 1 and 2 by taking maximum points. But it was behind them that Malizia first started to show its qualities in this part of the world. On the way to the imaginary gate—situated at longitude 143 degrees east—Malizia simply sailed past Mãlama in sight of her, as Amory Ross, the OBR on the American yacht, memorably described.

“They seem to be able to carry more sail and keep their bow up, and while we struggled in the waves to keep from nosediving, they were able to sail at the same speed but lower,” he wrote.

In an interview after the finish, Enright was a bit less diplomatic. “It was kind of at that point in the race that everybody realized that Malizia was this Southern Ocean downwind machine—right before the scoring gate—and we were like, ‘Oh f—,’ you know…”

While the first half of this Southern Ocean drama was dominated by Escoffier’s boat, the second act in the Pacific saw a restart at Point Nemo and then a dogfight at the front between Holcim and Malizia in the run down to Cape Horn in big weather. It was a battle that continued up the South American coast, when three depressions produced the roughest weather, with the breeze topping 50 knots on three successive days.

And it was on the run to the Horn in big breaking seas that Malizia crewmember Kuiper was thrown out of her bunk when the boat spun off a breaking wave. She landed on her head, inflicting a concussion and a nasty wound, an incident that only underlined just how dangerous these platforms are in heavy weather. But the tough 27-year-old Dutchwoman, who was one of the brightest stars of the OBR show on this leg, just laughed it off, comparing herself to a pirate with an eye patch.

The weather pattern after the Horn was a gift for Malizia and just what this band needed to hold Holcim off all the way to the finish. Herrmann and his jovial squad crossed the line in the early hours of the morning after 35 days at sea, having sailed 14,714 miles and with Holcim still 80 miles out.

“It’s taking a few days, to be honest, to really realize what we’ve achieved because the last few days were really intense, trying to make sure we stayed ahead of Holcim and just really guaranteeing that we were really going to win this one,” Harris said after the finish. The 29-year-old Englishman couldn’t help but look back to the mast damage early on and marvel at how they turned things around.

“It was such a big comeback,” he says. “If we think back to week two of the leg, it didn’t seem like winning was even possible, so I am very happy that we’ve managed to get there, and we’re all slowly realizing it.”

Harris was candid about Malizia’s performance woes in light air, but he reckoned the crew had mastered its weakest link: marginal foiling conditions in winds of 10 to 16 knots, when the boat is sluggish and won’t get up and fly. The secret, he explained, is to sail with as much heel as possible and load the leeward quarter with all the movable weight to take advantage of a flat spot in the hull. “For the first minute or two, the boat will feel very slow, and then suddenly, it builds apparent and it starts taking off,” he says. “We call it semi-foiling.”

Malizia’s performance in this leg moved them one point ahead of Mãlama into second place overall, five points behind runway leader Holcim. It was a bitter pill to swallow for Enright and his crew, who held off Biotherm all the way from before the Horn to the finish to secure the final podium position. They managed to do so despite trashing their mainsail when the autopilot dropped out, causing a violent crash jibe off the Argentinian coast. Biotherm was also wounded, having hit a submerged object and damaging a foil, and the Americans kept their mainsail damage secret while they effected a Herculean repair.

“We knew it was going to be tight with Biotherm at the finish by virtue of them being in the same weather system as us, so anything we could do to gain an advantage and get a jump on them we had to do,” Enright said in Itajai. “We knew that they were facing adversity too, and if there was a chance that by them not knowing the news of our mainsail damage, they would be complacent, even for just a few hours, they were hours that we desperately needed.”

Fisher, on his sixth circumnavigation, has experienced his share of challenges, but the bleary-eyed and unshaven faces of him and his teammates were all one needed to see to understand the toll this leg had taken on them, as well as their spares and tools.

“We always said it was going to be tough, but I don’t think we ever imagined it was going to be as challenging as it was,” Fisher said in a team statement after finishing. “As much as we would have liked to finish in first place, the fact that we’ve managed to get through this in spite of all the issues we have been dealing with over nearly 38 days is a great achievement.

“Jack has done a fantastic job as boat captain keeping the boat together, but there came a point in the leg that it wasn’t about winning, it was about getting to the finish line. We knew it would be difficult and long, but we all agreed that we should make the most of it. It was about setting the mindset and enjoying it; you can’t control what happens to you, but you can control how you react to it.”

Arriving in Brazil, Enright knew the pressure was on, but he was feeling confident the scales would turn back in his team’s favor now that the race had returned to the (supposedly) calmer waters of the Atlantic. For his sake, one would hope Harris’ new-found confidence about Malizia’s performance in medium conditions would prove misplaced.

“We definitely have a boat that is more comfortable, shall we say, in the Atlantic, and we are happy to have turned the corner,” Enright said. “If you could pick a boat for [Leg 3], you probably wouldn’t have picked our boat, but I’m happy with where we are at for the rest of the race.”

Enright placed a lot of emphasis on competitiveness at the end of an Ocean Race, not its early or middle stages, and he certainly wasn’t ruling out winning this edition with four legs still to go, including a transatlantic from Newport, Rhode Island, to Aarhus, Denmark, in late May.

“We’ve always maintained that we want to be the team that is sailing best at the end of the race and improve the most from day one until the finish, and we still have that opportunity,” he said. “No one here is worried; we’re just going to keep chipping away, and when you chip, you get chunks.”

Enright, 38, has been around the block in fully crewed ocean racing—this being his third Ocean Race—but he says he has not experienced anything like Leg 3 before.

“It’s by and away the most difficult thing I’ve done,” he says. “That’s not even from a conditions standpoint; it’s from a duration standpoint, but also the platform. There are people that have sailed in the South and people that have sailed IMOCAs in the South, and we are now in that category, and it’s no mystery to me why this class moves in four-year cycles.

“I tell you what,” he adds. “If I was doing the Vendée Globe, man, I’d want to do The Ocean Race. I’d want to get down there two years in advance and know exactly what we are dealing with, with the newest kind of design innovations in the boats and what have you.”

Harris, meanwhile, was hoping to get himself fit and healthy for the next stage from Itajai to Newport in late April. And the young Englishman was daring to dream that Malizia’s performance in Leg 3 could yet herald something even more magical for him and his team. “We’ve proved that we are a really strong team in terms of development, and that’s what this race is about,” he says. “If we can keep developing and learning faster than the others, we can certainly start winning toward the end.”