MayTechRiceSt

Technology drives the America’s Cup, and here, more than anywhere in the sport of sailing, is where you can always count on innovation. We’ll see plenty of it in Valencia this summer, especially in the details of each syndicate’s boat, but as the boats themselves are more evenly matched in speed, individual races may well be decided on boat- and sail-handling alone. This is especially true considering the windward legs are now only 2 nautical miles long. Short legs make for close racing, and close racing demands supremely efficient crew work: the tool for this is the all-important utility winch, or rather the “bitch winch” as it’s affectionately known among the crews. Located in the pit, immediately behind the mast, this elaborately machined tool is the most important sail-handling piece of equipment found on any ACC boat today.

“It was Stars & Stripes in San Diego in 1992 that introduced the idea of an extra winch,” says Phil Atfield, sailing marketing manager for Lewmar, who has been working with Cup campaigns since 1980, and was involved with Dennis Conner’s Stars & Stripes campaigns. “It enabled us to start hoisting spinnakers really quickly compared with the usual bloke by the mast, arm-over-arming it [the spinnaker] to the top.”

Lewmar|

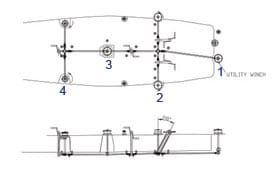

|Harnessing the Power****1. The utility winch sits on the forward part of the cockpit.****2. Two primary grinding pedestals and winches are immediately aft of the utility winch and are used to tack and trim headsails. As many as four grinders can be tasked for the big jobs like tacking and jibing. The small circles immediately aft of the primary pedestals are for shifting gears.****3. The mainsheet pedestal and winch powers one large winch for trimming the mainsail. In jibes, two grinders will be put to work.****4. Runner pedestal and winches are where the afterguard slaves away grinding the running backstays during each tack. Grinding a runner to 25,000 pounds of tension is hard work.|

To really understand the value of the utility winch, one simply asks any of today’s pitmen, such as

Jeremy Scantlebury, who is now with his seventh Cup campaign, this time as a systems consultant for Victory Challenge advising the Swedes on various aspects of the design and build of the boat, particularly on the winch and hydraulic systems that have gone into SWE-96. The Kiwi’s involvement in the event pre-dates the birth of the bitch winch, and through his five campaigns with New Zealand teams from 1987 to 2000, followed by his role as pitman for OneWorld in 2003.

“We started using a utility winch in the 1995 campaign,” says Scantlebury. “Initially we used it for gennaker jibing; we didn’t use it for hoisting in the early days. We had perfected bouncing the halyard so well that we felt we could do it quicker that way.” He estimates Team New Zealand got its spinnaker hoist down to 7 seconds using a two-man bounce, but he concedes the technology has improved since then.

As teams rely more on the utility winch it’s now the centerpiece of an increasing number of maneuvers. “Every Cup you see the utility winch being used more,” says Scantlebury. “Now everyone is using it as a hoisting and dropping tool, and a jibing tool when you’re using gennakers up the wind range.”

Lewmar| |Lewmar’s custom America’s Cup Class winches include the Model 111/4R, which is used as a utility winch, and is available in either three or four speeds. It has a working load of 5 tons, and coasts nearly $20,000.| As the America’s Cup and high-profile racing sales manager for Harken, Mark Wiss has privileged access to seeing how different teams use their winches; 11 of the 12 teams are using Harken winch packages. Team China has winches from Lewmar. “The bitch winch is very versatile,” says Wiss. “It used to be a back-up. Over the years it has become more purpose-designed, and more central to maneuvers.” The winch favored by Harken’s Cup customers is its model 1111, with a self-tailing top. Some teams favor three-speed gearing, but most use four-speed. The Lewmar equivalent used by China Team is its 111/4R winch, with a 280 mm drum. This particular winch has a working load of up to 5 tons and costs nearly $20,000.

The utility winch’s importance has grown, and so to has the number of grinders who can link into driving it. “Back in ’92, teams had four men linked into the primary,” says Wiss. “In ’95 it was two pedestals linked into the primary, then in 2000 it moved from four people up to six. Next thing, everyone is grinding and tacking six, until it moved to everyone grinding with eight guys linked into the winch. That has changed the way people sail these boats.”

Hoists and drops are now phenomenally quick, thanks to the introduction of overdrives during the last Cup. “This is the gear box which creates a 1-to-2 ratio,” says Wiss, “meaning you double the line speed but halve the power. As the load comes on to the halyard you shift down a gear.” The limiting factor has always been that the best grinders can only turn the handles to a maximum of around 200 RPM. “If you insert the overdrive,” says Wiss, “200 RPM becomes 400 RPM, and when you bring eight grinders into the system you can hoist and douse spinnakers quickly.”

Lewmar|

|Eleven of the twelve America’s Cup teams competing in this year’s event are using winch packages designed and built by Harken. Shown above is their version of the utility winch, the Model 1111.|

David ‘Freddie’ Carr is the youngest member of the Victory Challenge sailing team, and the 24-year-old Briton operates as a floating grinder for the Swedes, a human version of the utility winch. “The bitch winch is the hardest working winch on the boat,” he says. “It’s the only powered winch in the pit, and it does so much work that we

service it twice as much. We pull the bevel box apart twice a week, just to be sure.”

Carr started his Cup career crewing for GBR Challenge in Auckland in 2002, and in his relatively short career he has seen significant developments in boathandling, largely thanks to the winch and overdrive systems. “When you link four pedestals (eight grinders) into the utility winch you can hoist the spinnaker in less than six seconds,” he says.

The other big development of recent years has been the “string drop” at the leeward mark. In this maneuver, rather than manhandling the spinnaker through the hatch in the foredeck, teams are now using a retrieval line system. Linked into the utility winch, the string drop system can suck a spinnaker down from the masthead smoothly and into the bowels of the boat in a matter of seconds. On the short courses of today’s Cup race, this is an integral part of a team’s boathandling repertoire, so much so that the interiors of the hulls are configured specifically for string drops.

Perfecting a good string-drop routine gives a team all kinds of tactical advantages, says Carr. “When you’re nip-and-tuck with another boat downwind, whoever gets to the three-boatlengths zone around the leeward mark has all sorts of advantages. So the string drop is vital for tactical reasons, and when a crew has the technique well practiced, it gives the helmsman confidence when he’s heading for the leeward gate. In the old days it would have been five guys up on deck hauling in the spinnaker, so you’d be dropping six or eight boatlengths before the rounding. Now, as the bow draws level with the mark it will be, ‘Go, drop line!’ and we should have the spinnaker down and away before the stern has passed the mark. A well-executed string drop means you can get the spinnaker down within a boatlength.”

Technically, and physically, the toughest maneuver-on sailor and winch-is the asymmetric spinnaker jibe in moderate to strong winds. There’s a common misconception among America’s Cup observers that asymmetric spinnakers are faster in light to moderate winds, up to 12 knots for example, whereas symmetric spinnakers are faster in stronger winds. Carr says this is not necessarily the case. The asymmetric is nearly always faster, but is increasingly harder to handle up the wind range. “Ten years ago teams might have been flying their asymmetric sails in 14 knots. Now we’re trying to hold it in 18 knots.”

The problem with the asymmetric spinnaker is the difficulty in jibing it Not only is it slower than jibing an asymmetric sail, which floats beautifully all the way through the jibe-it’s a move that can go severely wrong. It requires eight grinders to sheet in 30 feet of foreguy quickly. However, the utility winch allows crews to grind the jibed pole aft toward the shroud, which is exactly what teams have been practicing. Carr says jibing the asymmetric in strong winds is the benchmark test of any team. “It’s probably the hardest maneuver to get right,” he says, “but the better you get at handling the asymmetric into the upper wind range, the more tactical options you have. Running the line off the utility winch opens up the potential for double-jibing and fake jibing.”

The other significant use for the utility winch is hoisting the wind-spotter up the rig. “Before the utility winch,” says Carr, “it would have been two guys bouncing a man up the rig. So once he was up there he tended to stay up there. Now it’s easy to whiz someone up and down the rig, so it’s a snap decision for the tactician. For example, you might not want an extra 175 pounds up the rig going upwind in a choppy sea, but you could hoist a man up before the windward mark, to look for puffs on the downwind leg.”

As teams have gained confidence and experience using the utility winch for more and more tasks, they’ve reduced the number of other winches in the pit. On earlier-generation boats there might’ve been three or four additional winches; now there are one or two. This is all with the aim of reducing weight on deck and putting it into the lead bulb 15 feet below the surface. Fundamental to the elimination of winches is the development of line-holding jammers. “Back in the days of IOR boats or even the 1992 Cup,” says Wiss, “it was one winch per halyard. Now the jammers are so strong that you can lock off even the most high-load lines on a jammer, freeing up your winches for other jobs.”

Wiss is surprised at both the similarities and differences between the teams, but he and his colleagues at Harken operate a strict ‘Chinese walls’ policy. He’s aware of customization, but he’s unable to disclose details. “There are many ways to set up a boat and specialize the system,” he says. “It could be anything from varying gear ratios to gear boxes, there are lots of different areas to work on. But once the Cup cycle is over, more or less all bets are off.”

Of course once the Cup is over sailors may see a trickle-down effect. Already the utility winch has become a must-have item in the high-tech TP52 class. Phil Atfield says it has been adopted by many of the new breed of Supermaxis, and even the big classics. To date, the Volvo Open 70s haven’t used utility winches, as the extra weight meant less weight going into the keel bulb. However, with a change of rule for the next race, the arrival of the bitch winch wouldn’t be a surprise, particularly if the event’s in-port races account for a larger percentage of the available points.

No one involved in the America’s Cup has any doubt of the central role of the bitch winch. “Every team takes the utmost care it,” says Carr. “Your boathandling is utterly reliant on it. If it’s not working, it will probably lose you the race.”