Conor Fogerty was feeling it. Aboard the husky, well-prepared Beneteau 44.7 Black Magic, with Fogerty on the wheel, we were closing in on the fifth day of the 700-plus-nautical-mile SSE Renewables Round Ireland Race. Having just passed Thor Rock, we were fast approaching Rathlin Island, the northeast corner of the Emerald Isle’s rugged, wild coastline. The lights of Scotland blinked on the far horizon. The next 24 hours would unfold like a fever dream. But first we had to negotiate dark, craggy Rathlin.

The island marks the crossroads between two converging ocean currents, where the North Atlantic jumps the Irish Sea. It was more than a bit messy. Before the race, I’d heard many a Rathlin horror story; boats had been known to park there, anchor deployed, for double-digit hours if they happened upon it when the tide was foul. Rathlin has converted many race leaders into race losers. It’s not something for which you can plan ahead: You get there when you get there.

Luckily, we nailed it perfectly.

I was grateful that Fogerty was at the helm. Just before the start, I’d been informed that I’d be sharing both watch and driving duties with him, which was daunting. A professional delivery skipper, he had 35 transatlantic voyages to his credit, including a victory in the grueling 2017 edition of the OSTAR singlehanded race aboard his Jeanneau Sunfast 3600, for which he was named Irish Sailor of the Year. For the most part, I’d hoped I’d held my own, but something had also been made crystal clear: I’m no Conor Fogerty.

As we passed the blinking lighthouse off Rathlin’s headland, the speedo registered a modest 4 or 5 knots, but the adjacent GPS numbers told the larger story of the favorable escalator on which we rode: 12.5 knots. At that moment, under Fogerty’s steady hand, Black Magic creamed into a cauldron of swirling current, the intersection of boat meeting sea putting us briefly into submarine mode. A drenching wall of water swept the decks and filled the cockpit. I remember thinking, This is June, and that effing wave is too damn cold.

A few hours later, at dawn, we were once again in open waters. With roughly 75 nautical miles to the finish line off the town of Wicklow, and 35-knot gusts right on the button, the northern shoreline was behind us. It was the home stretch. The good news? We were back in the Irish Sea. The bad news? We were back in the Irish Sea.

My unlikely tale of scoring a ride on Black Magic began almost a year earlier and in an unlikely place—at the annual Fleet 50 J/24 awards ceremony in my hometown of Newport, Rhode Island. Earlier that summer, with the same knuckleheads I’ve raced J/24s with for decades, we snagged for our fifth man a bright, savvy Irish kid named Jack Cummins, who was teaching sailing at the Sail Newport community sailing center for the summer. I mentioned to Cummins that, despite my Irish surname and ancestry, I’d never visited Ireland. If I ever made it, I wondered, might he show me around?

“You should come do the Round Ireland Race,” he replied. “My mom used to be the commodore of the Wicklow Sailing Club that runs the race. I can get you on the boat I’m sailing on.”

The rum was flowing and, I reckoned, likely doing the talking too. All of which led up to this past April, when I received this email from Black Magic’s owner, skipper and navigator, seasoned Irish yachtsman Barry O’Donovan: “Jack Cummins has mentioned that you are interested in doing the Round Ireland Race this June. We have a good, energetic crew lined up and would be delighted if you would join us. Let us know your thoughts?”

It was an offer too good to pass up. Now I just had to figure out exactly what the Round Ireland Race was all about.

The first edition was in 1980, with a fleet of 16 boats, and it has run biennially ever since (with the exception of the COVID cancellation in 2020). It generally draws a strong UK entry list, though George David’s Rambler 88 represented the US in 2016 and set a monohull course record of just over two days. These days, it’s sponsored by SSE Renewables, an operator of onshore and offshore wind farms.

Those are the hard numbers, but the heart of the event—and I’d soon learn that, as with everything Irish, soul and spirit are paramount—comes from the funky little grassroots club that runs it. There are far more prestigious yacht clubs in Ireland, such as the Royal Cork, that would love to host the country’s premier offshore race. But it’s the biggest undertaking by far for the unpretentious sailing club and the cool little town of Wicklow (St. Patrick himself is said to have landed on its shores). It seems that practically every member volunteers in some capacity, and once the race is underway, the clubhouse remains open 24/7. No matter when you finish, frothy Guinness awaits.

“Energetic” was an apt description of the Black Magic crew. Ciaran Finnegan was the de facto boat captain, who’d been sailing since he was a wee lad. His right-hand man was his fellow Round Ireland vet, Robert Kerley, who could impressively hand-roll cigarettes in a small gale. Joss Walsh was a 6’4” all-around waterman built like a linebacker (always good to have one of those dudes on hand). My J/24 mate Cummins fit right in with this tight band of Celtic brothers.

On the other hand, O’Donovan, Fogerty and I constituted the geriatric over-60 set. We were accorded respect from the young brothers as the elders we were.

Surfer Peter Connolly and Dominic O’Keefe, who kept everyone well-fed, rounded out the male majority. The lone woman on the team was O’Donovan’s daughter, Labhaoise (pronounced LEE-Shuh), an excellent sailor who also served as the no-nonsense crew chief. I was told at the outset to stay on her good side, and I tried my best.

It was a tight, good-natured and often hilarious bunch; I often felt like I’d been beamed onto the set of an Irish boating sitcom. And, as I was soon to learn, they were some badass sailors too.

The sailing instructions for the 704-nautical-mile contest are deceptively simple: “Leave Ireland and all its islands excluding Rockall to starboard.” The mileage suggests a distance race, but the weird fact of the matter is, you’re never all that far from shore. That’s not the only confounding issue.

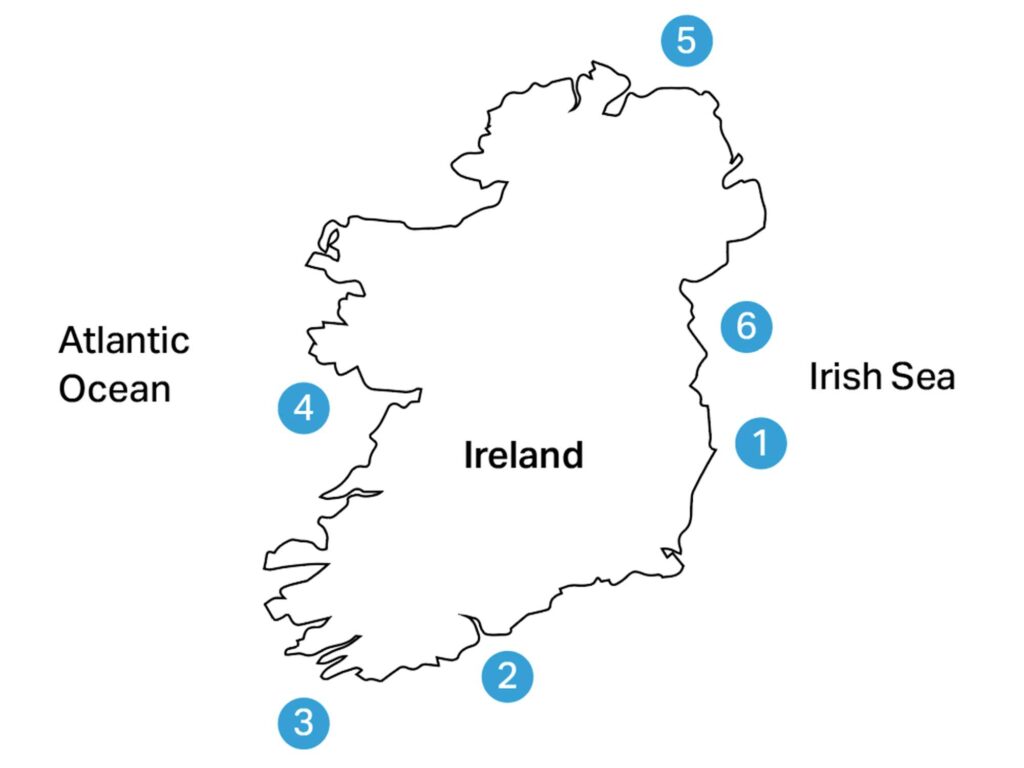

At the club before the start, I asked three-time race veteran Tim Welden for his take on the racecourse. “In fact,” he said, “it’s 13 different races, from headland to headland. There’s different breeze and currents at each one, and you restart every time. You get a taste of everything, all points of sail. Light winds, heavy weather. Night and day. Dozens of watch changes. Don’t let anyone tell you it’s a pretty race. It’s really hard. Then there’s the elation of finishing. You know you’ve done something.”

A 45-knot gale in the open Atlantic was the miserable lowlight of the 2022 race; Kerley sailed it on Black Magic and recalled it vividly. “It was humbling,” he said, with a faraway gaze. “That’s what offshore sailing does. It humbles you. What you thought you were good at…” His voice trailed away, leaving me with my own humbled thoughts: What the hell had I gotten myself into?

With that, on June 22, we were outbound from Wicklow Harbor. It was a gorgeous day, with bright sunshine and 14 knots of southerly breeze, and the Irish naval patrol ship George Bernard Shaw on station at the starting line. Over half of the 48-boat fleet flew foreign flags, a point of pride to the Irish, who are keen on hosting an international event. Spectators were perched on the rolling, emerald hills above Wicklow, the sort of scenery that inspired Johnny Cash to croon about the “40 Shades of Green.”

I was glad that I took it all in because the world around us would soon close down.

The first 150 miles or so were largely a light-air beat, much of it in heavy mist that made steering a challenge; with zero visibility, the horizon vanished, with no clean demarcation between the sea and the sky.

There’s one word to describe the Irish Sea: ghastly. The edgy seas are short and angry. There’s no carving through it; you just pound into it.

I had but one bucket-list wish for the entire race: to get a close look at iconic, legendary Fastnet Rock. O’Donovan had whetted my appetite further by saying that the stretch from Fastnet around the coast of Kerry—past Mizen Head; the Bull and Calf Rocks; the Great Skellig Rock, where monks built beehive huts centuries ago; and the Blasket Islands—was his country’s most scenic coastline. Alas, we passed within a mile of Fastnet, socked in by heavy fog (I may as well have stayed in Newport), and never saw a bloody thing, nor any of the other landmarks.

“Just the sound of the sea breaking on them,” O’Donovan said.

“Don’t worry,” Cummins said. “It’s just a rock. The important one to see is back off Wicklow. That’s where we’re going.”

For a while, it seemed as though we’d never get there; soon the breeze disappeared entirely. We watched in dismay as several boats, just a mile or so away, did end runs around us. “We are in the hole from hell,” Fogerty said.

Eventually we escaped into the Atlantic. Historically, this is the juncture where the ocean swells begin to appear, accompanied by a fresh southerly, promoting a spinnaker run northward up the west coast. For a while, we had just that, with 25 knots of favorable breeze as we downshifted kites from the A1 to the A2, and for a spell registered speeds of 10s and 11s. We still couldn’t see a damn thing, steering by instruments. But at least we were finally moving.

At long last, sliding past the coast to Galway, the sun made an appearance, and we enjoyed some of the prettiest sailing of the entire trip. Happily, I could now see what we’d been missing. Even at midnight, it never really got dark, with a glowing red sky juxtaposed against the green, green coast. Unfortunately, the breeze had swung north, and we were back charging upwind into it. Getting dressed to come on deck was a stumbling dance, and once on the wheel, it was hard to get into a groove.

“It’s like having sex for the first time,” Walsh said, when I asked if he had any steering tips. “You have to feel around in the dark for a bit. But at least now you know why so many Irishmen move to the States.”

And, it occurred to me, why they love golf.

Once along the northern shore, it was one sail change after another, and we got to see the whole inventory: kites, jib, genoa, code zero. Though none of them were up very long. Also, we were lucky; we’d missed a nasty low-pressure system that had formed behind us, a full-fledged gale. Nearly a dozen boats retired, bailing into the many little sheltered harbors dotted along the Atlantic coast. At least Black Magic was still a going concern.

Then, fortuitously, we slashed past Rathlin Island, and the end was nigh. Which is when O’Donovan had one final, sobering announcement. Another potent low had cropped up, packing a punch. Dead ahead. In the Irish Sea.

With Rathlin astern, Cummins had an observation: “Chutes and ladders, that’s what this race is about.” Indeed, we’d been shot with dispatch into the Irish Sea. One more day to go. It turned into a long one.

We were hard on a building southwest breeze, which would fill all day long. It occurred to me that we were five days into it and had enjoyed downwind sailing for perhaps 10 hours. On a day like this, there’s but one word to describe the Irish Sea: ghastly. The edgy seas are short and angry. There’s no carving through it; you just pound into it. Especially as the breeze mounts into the 20s and 30s. The first reef went in. Then the second. The bright spot was that we were on a starboard-tack fetch to the finish.

Of course, there was one more bit of drama. Black Magic was apparently as tired as we were. The mainsail battens started to pop, the leech line gave up the ghost, and it felt as if the whole sail might fail. Which is when the A-team—Finnegan, Fogerty, Kerley and Walsh, which could be the name of an Irish law firm—went into action, cracking off and basically nursing the whole shooting match onward. Later, O’Donovan would say: “We had a following tide for most of it, which could have carried us past Wicklow if we’d lost the main. It was the best crew work I have experienced in my long time at sea.”

I spent the last few hours on the rail alongside Cummins, who offered a geography lesson as we slipped down the coast: Howth, Dublin Bay. Finally, up ahead: Wicklow. Then, just before midnight, after 5 days, 10 hours and change, the finish line. Our results were middling: fifth in IRC Two, 21st overall. No matter—I remember what I’d been told I’d feel: elation. It was true. It all felt like victory to me.

Four boats had finished within the hour, and the Wicklow clubhouse was rocking. The first Guinness was heaven. Next came a piping-hot full Irish breakfast: fried eggs, bacon, sausages, baked beans, black pudding, thick toast and delicious Irish butter. Easily one of my top all-time repasts.

There was just one final mission: Before the race, the Cummins family had basically adopted me, and with its conclusion, Jack’s parents granted my wish to take a quick road trip back down along the southern coast, to see from land where we’d passed by sea. We paid a quick stop in Kinsale, a sister city to Newport, and scarfed down fish and chips at the Fifth Ward Bar, so named for an iconic local neighborhood. It felt like closing a circle.

But the best part was driving up to the proud Kinsale Heads outside the city. Just a few days before, I’d been at the wheel on one of the sunniest days of the race as we engaged in an inshore tacking duel with Nieulargo, a Grand Soleil 40. From high above, I replayed every tack, every cross of one of the most memorable sailing days of my life. With that, my Round Ireland Race adventure was officially in the books. What more can I say? It was all grand craic.