It didn’t take long for the sailors to begin referring to their big tri as “The Beast.” The media were calling it Dog-Zilla, a play on the acronym for Deed of Gift. Everything about it was big, heavy, beastly. Today’s computerized design tools will tell you everything you want to know about a boat’s performance in all conditions and configurations, so while the data that registered about loading revealed no surprises, the numbers were sobering when they represented larger-than-life-size realities sailors had to contend with hands-on. There was a 75-ton compression load on the mast step, 32 tons on the forestay with the mainsail sheeted on, 24 tons on the mainsheet. The wingsail would tame that to 4 tons.

Bowman Brad Webb, who previously sailed with TAG Heuer in 1995 and America True in 2000 before joining the original Oracle team for the 2003 Cup match, said the first day they sailed in Anacortes they had five jibs on the boat and a crew of 16. “Things were heavy and hard,” Webb says. “Sails weighed around 300 to 400 kilos each (660 to 880 pounds). It took five people to move them. We craned them on board at the dock, and used halyards to move them to and from chase boats.”

Joey Newton, who worked the mid-deck, had the job of getting sails aboard before leaving the dock. He says it was a huge logistical operation just getting off the dock. “It wasn’t like a normal boat where you can grab five guys and pick up the main,” Newton says. “We needed cranes and special booms to pick up the sails. Just to put the cable in the luff of a gennaker we had to get a 10-ton truck and two forklifts to get enough tension on it, then get the sail coiled and lashed up on the dock. Getting sails on board in the morning while other guys were busy at their jobs on the boat at the same time was dangerous. I had horrible thoughts of halyards or clips breaking.”

For several months, the whole crew sailed wearing hard hats and life jackets. “I was terrified on a daily basis,” Webb says. “The first day when we did load testing, we had stuff falling out of the sky and missing people. In San Diego, we had blocks tearing off the deck and strops breaking. There was always something breaking. As much engineering as there was in the boat, it was on the hairy edge. It’s the most extreme sailing craft ever put on the water. After a while, we got used to what might break, what looked right and what didn’t, where you could stand at any given time and be safe. So we finally got rid of the hats and jackets to reduce weight and windage. But we still couldn’t account for surprises.”

John Kostecki says “terrifying” is the right word. “Let me put it this way,” Kostecki says, “I was more scared on this boat than I was at any time during the Volvo Race. It wasn’t just a little scary; it was scary. We had great designers, great engineers, great sailors all coming up with a boat that was changed radically along the way, everything was as light as possible, it was incredibly loaded, there were unknowns here and there, we didn’t know how hard to push, and we had only a certain amount of time with the new design configurations. Yes, it was scary.”

The boat had four positions on the mast for headsails. Each position had two halyards: one for a designated forestay for the sail, the other for the sail. During the weeks of testing, a sail change could take an hour. “We’d start out by hoisting a genoa,” Webb says. “Then they would call for the next sail down we named the Solent. We’d drop the jib, take the headstay off the lock, and lower it. Then we’d use the halyard to put the sail on the chase boat, hoist the Solent aboard, hoist the Solent forestay into place and lock it, then hoist the Solent.”

They experimented with sails with old-fashioned hanks, and discarded that idea. “Hanks were a nightmare,” Webb says. “If we couldn’t keep the sails on the net—with 45 knots of wind across the deck—and they went overboard while we were going 25 knots, we’d never get them back.” They tried jack lines, and those didn’t work either.

The netting that spanned the water between main hull and floats would eventually disappear. In October 2008, longtime Cup sailor and ocean-racing veteran Matt Mason would conduct a one-man operation to lighten ship. He removed more than 900 kilograms of gear he deemed nonessential. The safety netting was one of the first things to go. Mason would later join the boat’s crew and have to watch his step like everyone else.

Jim Spithill, standing on his helm platform attached to the windward end of the aft beam, was often 10 to 15 meters (35 to 50 feet) above the water. His safety rail disappeared in Mason’s nonessentials purge. “It was like being in a hurricane up there,” Spithill says. “Sailing in 15 to 20 knots of [true] wind, and with 25 to 35 knots of boatspeed, I was standing in 40 to 50 knots of apparent wind all day. It drained my energy. It would weather you. And I couldn’t hear a thing. That’s why we all wore headsets.

“My biggest job was keeping track of the loads. I had a heads-up display in my sunglasses, like a fighter pilot has on his canopy. Wearing them was difficult to get used to. I walked into a couple of posts on the dock. But I got used to it. We were always on the edge, sailing at 100 percent all the time. We had a dozen alarms on the various sensors that were everywhere—forestay, backstays, daggerboards—and they were constantly tripping. The alarms drove everyone crazy. I was watching everything and passing the word—crank on that, ease this—all the time. We also constantly monitored weight to windward because we had a righting moment to live by. It all came down to how close to the edge you wanted to get, how much you wanted to eat into the safety factors.”

Larry Ellison agrees that the boat was terrifying, “at least initially, with the soft sails, when I first drove it. It had [bicycle] chains coming off the wheel, and there was no feel, no rim load. It didn’t feel like sailing to me at all. I had to learn how to sail again. I watched Jimmy drive. When he wanted to head up, he would throw the helm over hard and skid the boat sideways, then straighten it out, and repeat the process—helm over, skid, straighten out—until he had his new course. It was like drifting a car around a corner.

“I learned to drive it by heel angle. I watched the middle hull. If it was lifting a little too fast, I’d head up; if it was falling too fast, I’d head off. Heel angle and the speedo are the two things I watched when steering, and you could get into the rhythm of it.”

Spithill likes the edge. He rides motorcycles, kitesurfs and boardsails for fun. The day the wingsail was given the go-ahead, Spithill began taking flying lessons. It seemed appropriate. When he learned about the edge factor in multihulls, his interest was piqued. Glenn Ashby, who returned to BMW Oracle Racing full time in February 2009, after winning his Olympic silver medal, drove that point home. “I liken multihull sailing to Formula 1,” Ashby says. “The guys who do the best are the ones who can keep the pedal down the hardest and longest. If you don’t push hard, the penalty in boatspeed loss is great. You don’t lose a tenth of a knot like you do in a monohull. You lose 2 to 4 knots. You have to sail accurately, on the edge, achieve maximum performance at all times. All the design and technology are of no use if you are sailing at only 80 percent.”

Spithill says that early on in training camp he had a conversation with another multihull champion who had stopped by to sail with the team: Roman Hagara from Austria. Hagara has won gold medals in the Tornado in both the Sydney (2000) and Athens (2004) Olympics, and two Tornado world championships. “We were talking one day before racing,” Spithill says, “and it was pretty windy. I remarked that sailing on days like this must feel dangerous. And Romy said: ‘Yeah, any time you want to be fast on a day like this, you’ve got to be dangerous. You’ve got to be on the edge.’ I’ll never forget that because he and Glenn were going on about it.”

Webb wasn’t on board the day the bowsprit broke for the first time, late in 2008. “It spooked the guys,” Webb says. “We broke it several times and realized we had an inherent problem. I stayed well away from it. I never went out on it when we were under load. If I had to make an adjustment, we’d bear away, unload, and I’d go out. We were good about that in all areas. We never put anyone in danger. We unloaded first, got the job done, and loaded back up.”

Everyone on board realized this user-friendly system of unloading could not be applied during an actual race.

Another question about race readiness had to do with the physical challenge the boat presented to the grinders, historically those National Football League linebacker types who man the large-diameter pedestal-driven winches. USA 17′s eight grinders were impressive physical specimens in addition to being good sailors. They lived in the gym, and all of them could bench-press small cars. But at his peak, a top-ranked grinder can generate one-quarter horsepower for about 60 seconds. Four grinders are sufficient on most “normal” big boats. But on the Beast, with all eight men putting out full effort on four interconnected pedestals, producing a total of 2 horsepower, it was taking three minutes before the mainsail was fully trimmed after a tack. The long delay getting the main in was causing Spithill to drive very creatively to keep speed up until he could once again reach the upwind targets. That was just another problem that would have to be solved before race day. ν

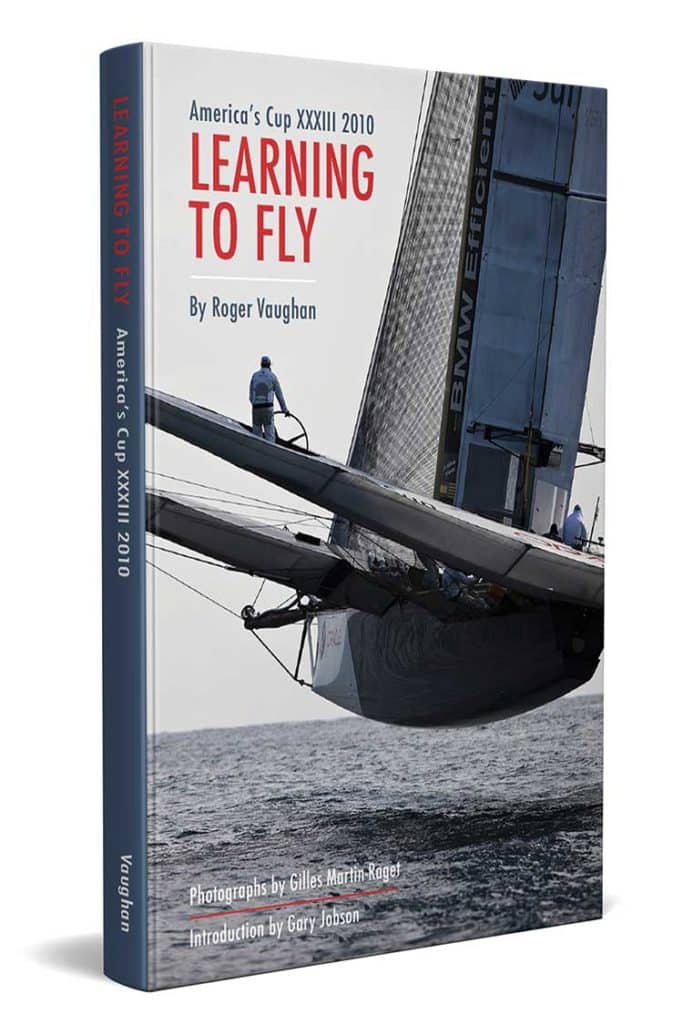

Roger Vaughan’s Learning to Fly—America’s Cup XXXIII 2010 provides a missing piece of America’s Cup history that bridges the gap between 156 years of monohulls sailing for the Cup, and the high-tech craft now foiling for the Cup. Available in Kindle and paperback at amazon.com.