Tony Lush was in trouble—the deep, dangerous sort that you can get yourself into only when you race sailboats alone across vast oceans. It was late November 1982. Two weeks earlier, Lush had set sail from Cape Town, South Africa, bound for Sydney, Australia, on Leg 2 of the inaugural BOC Challenge solo round-the-world race. The night before, his 54-foot Lady Pepperell had pitchpoled in the Indian Ocean—“a somersault with a twist” is how he later described it—which he confirmed by noting that the masthead instruments on his cat-ketch rig had vanished. Those spars were still standing. The larger problem was the twisted keel that appeared ready to fall off.

In a race full of characters, Lush stood apart. Several years earlier, he’d gotten into singlehanded sailing as a student at Michigan State. Though he’d never sailed offshore or even owned a boat, he decided to build one himself—a plywood 28-footer with a junk rig that he named One Hand Clapping—to compete in the 1976 OSTAR solo transatlantic race. His reason? “I wanted to see if I really liked sailing.”

He finished 75th (dead last) but competed again in 1980, and parlayed all that into a sponsored ride for the first BOC. Which was now, unfortunately, broken beyond repair.

I know all this because I wrote a book called Out There about that race, which included Lush’s happy ending: Another American, Francis Stokes, came alongside Lush’s compromised vessel and whisked him safely to Sydney. It was the first of what became many dramatic Southern Ocean rescue stories in the years and races to follow.

For me, this rather winding tale came full circle when I was tipped off about a very different young American solo sailor, of an entirely fresh era, by the name of Erica Lush. Sound familiar? Yep, Tony’s daughter.

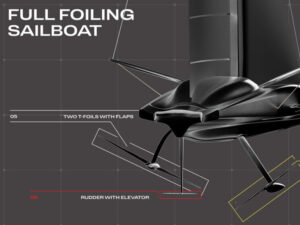

With the advance of foiling IMOCA 60s and scow-bowed Class 40s, shorthanded offshore racing is a whole new ballgame, and homemade woodies need not apply. And 33-year-old Erica is attacking it as the high-stakes hardcore contest that it has totally become.

Since January, Lush has been based in Brittany, France—the sport’s epicenter, with its decidedly French accent—with the goal to compete in this fall’s Solitaire du Figaro, a three-stage series of offshore races that has launched the careers of numerous Vendée Globe winners. She’s chartered a Beneteau Figaro 3 for the season, which began as one of 15 trainees at an all-encompassing on-the-water academy called the Lorient Grand Large, which she describes as “basically a university for offshore sailing.”

Lush’s first race is an elite 450-nautical-mile qualifier in March called the Solo Guy Cotton, followed by another qualifier in May. Assuming those go well, she still needs to find the dough for the actual Solitaire, which she describes as “the equivalent of three Bermuda Races.” She has received funding from the New York YC’s Performance Sailing Fund, as well as 30 individual donors, and is also seeking contributions via her website (lushsailing.com). The entire quest has a pioneering aura.

“I’m hoping to attract corporate sponsorship as a part of my goal to carve a pathway for more Americans and more young women to enter the higher levels of the sport,” she says. “The French have a different situation over here, but I believe that their business model can translate well to an American company with European interests.”

Lush’s personal journey has taken her over 75,000 nautical miles, including high-latitude racing through the Southern Ocean and around the three great southern capes. But all those miles had to start somewhere, which in her case were the relatively placid waters off the coast of Rhode Island. Tony ultimately retired from solo racing and settled down in the seaside town of Jamestown. His new bride and Erica’s mom, Nancy, brought a C&C 29 to the marriage, aboard which Erica got her first taste of sailing on family jaunts on Narragansett Bay.

That led to sailing classes at the local Conanicut YC. One day, Tony was waiting as Erica came screaming into the dock on her Opti, a moment he remembers clearly: “She pulled a U-turn, timed it perfectly, and came to a stop right at the foot of the instructor. OK, I thought, this kid’s got the hang of it.”

The racing bug didn’t bite hard until she joined her high school sailing team and also started competing in high-level summertime junior regattas in the 420. In choosing a college, she loved languages and knew that she wanted to study linguistics, but at a school where she could also race competitively. Boston University offered both, and she excelled in the classroom and on the water, earning her BA in linguistics with a minor in Arabic and speech pathology, and captaining the women’s sailing team.

As it turned out, her degree proved to be an ideal path to her ultimate occupation. When she couldn’t land even an entry-level position in her chosen field, she pivoted to something else she already knew: sailing. (It must be noted that Lush has found her language skills to be extremely useful, if not professionally, in nonprofit work in Jordan and India. “She’s a caring person,” her dad says.)

Across the water from Jamestown, Newport is a great place to launch a career in professional sailing. Lush started off as crew in the busy 12-Metre fleet, aboard the classics Gleam and Northern Light, but she eventually found her way aboard two-time America’s Cup winner Intrepid, which had an active program both racing and chartering. She eventually became the boat’s skipper and captain, became more and more familiar with systems and mechanics, and earned her US Coast Guard captain’s license along the way. When she wasn’t on the Twelve, she started doing deliveries, all of it one step at a time.

“Slowly, slowly, I was climbing the ladder, sometimes up and sometimes sideways,” she says. “Just trying to find jobs that were challenging and interesting—and offshore.”

A stint on an IMOCA 60 with the Canada Ocean Racing team, and aboard the Class 40, L’Occitane en Provence, brought new insights and experiences in the realm of shorthanded ocean racers. She found strong female mentors on all-women programs in Kiwi Sharon Ferris-Choat, when she signed on to a stint with the Magenta Project, and Liz Wardley of the well-known Maiden campaign. Aboard the latter, Lush did the two rugged Southern Ocean legs in the recent Ocean Globe Race—the 50th-anniversary tribute of the original Whitbread Round-the World Race—with the 58-footer taking top IRC honors.

Afterward, with well-known American solo sailor Tim Kent, she represented the US at the 2024 Offshore Double-Handed World Championships, and then set out with Kent in the Double-Handed division of the most recent edition of the Newport Bermuda Race. Midway through the race, things were looking great. “We were passing boats and doing well, then I heard a bit of flapping,” she says. Long story short, the heavy-weather jib was toast; the race over. “It was a hard call to turn back, but probably the right one.”

When asked about her long-term goals—a Vendée Globe, anyone?—she pauses. A year ago, delivering a scow-bowed Class 40 called Curium Volvo from France to Charleston with a three-person crew, they slammed into a whale off Newfoundland, causing extensive damage. They were able to limp home, but it left a lasting impression. “If that happens in the Southern Ocean, that’s a serious risk. I was pretty anxious the next deliveries I did. But I got steadier and back in the saddle.”

For now, she has plenty on her plate with the Solitaire du Figaro, though she doesn’t rule out grander goals: “The Globe 40, which is going around the world doublehanded, would’ve been a pretty cool learning opportunity. I’m really focused on the development side. Results are good, of course, but I just really want to become a stronger sailor.”

All that said, given her father’s long-ago crash landing, one has to wonder: Is her chosen pursuit ever discussed around the dinner table?

“It was a long time ago,” Lush says. “We sort of heard this story about this crazy thing that happened. But I’ve never had that discussion with him.”

Tony, for his part, doesn’t seem the least bit fazed about the unusual course his daughter has chosen. “She’s willing to learn and has done it with a lot of other people,” he says. “That’s a huge advantage. She’s far better prepared for this stuff than I was.”

He always was a straight shooter, so he deserves the last word: “Oh, and she’s just a much better sailor than me.”