At over 5,000 feet deep, Lake Baikal is the deepest lake in the world and the largest by volume, holding approximately 20 percent of Earth’s unfrozen fresh water, more than all the Great Lakes combined. The lake formed from a rift valley in the heart of Siberia 25 million years ago. Because of its isolation, life in Lake Baikal has evolved in amazing ways. Nearly 80 percent of the lake’s species are not found anywhere else on the planet, and perhaps that includes the hard-water sailors who travel great distances to race on the magical surface for Baikal Sailing Week.

Proper ice sailing is best performed on smooth ice with consistent winds, conditions most often found along the so-called Ice Belt, between 40 and 50 degrees N. With its dry climate and extremely long winters, Baikal is basically ice-sailing nirvana. The vast landscape is raw, remote and unspoiled. It’s far off the grid. My first impression of ice sailing was that it was technical, similar to foiling. The addictions to the two disciplines are nearly identical, with the objective being to go fast. With cruising speeds around a mile per minute, winning strategies are less about tactics and more about pushing one’s threshold. Skating around buoys at automobile speeds is no big deal; it’s the norm.

Because of such high speeds, conducting safe races is of the utmost importance. If a boat capsizes, hits a hole in the ice, or smashes into something, the skipper gets ejected and slides across the ice like a curling stone. Of the three crashes I witnessed at Baikal, two were caused by invisible gusts of wind that blew boats over and sent their skippers soaring. An Austrian sailor ran over a hole created by the famous Baikal seal, the only freshwater seal species on Earth. Only his leeward runner submerged, tearing the DN’s crossbeam apart and saving him from a Siberian swim.

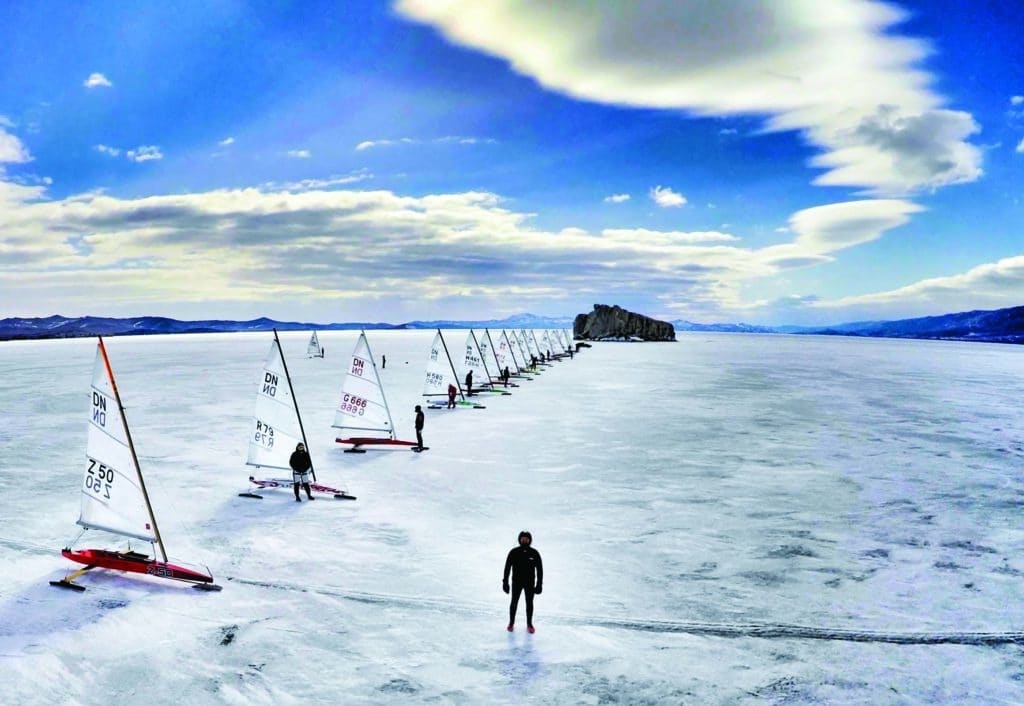

To prevent midrace collisions, racers line up side by side, with half the fleet required to go left and the other half right. Courses are typically windward/leeward, with exclusion zones around the buoys to prevent kamikaze layline approaches. The process for finding the best VMG is similar to that of foiling. As the boat accelerates, it produces stronger apparent wind, propelling it even faster. With minimal drag, ice boats seem to defy physics, finding power in even the faintest breeze. The sensation of a rig loading in less than 3 knots of wind is like black magic.

I journeyed to Baikal to shoot a Waterlust film about how ice sailors are uniquely sensitive to Earth’s climate. As a scientist, I’m fascinated by their perspectives; many have been competing for three decades. The dramatic reduction in sailable ice throughout Europe during this time has greatly affected the sport, and the creep of global warming means that many sailors must travel farther north and east to find good ice. Baikal, therefore, may become one of ice sailing’s epicenters, not because of its stunning views and strong winds, but because it is one of the only places left to find good hard water.