Leg 7 from Auckland to Itajai, day 03 on board Sun Hung Kai/Scallywag. Libby Greenhalgh at the nav station planning the next move. 20 March, 2018.

Late in the afternoon on January 6, 2018, the Volvo Ocean Race fleet was charging northward at more than 15 knots across the Coral Sea, sailing a leg of the race from Melbourne, Australia, to Hong Kong. The Volvo Ocean 65s were many miles from the nearest port. SHK Scallywag, in last place on the position reports, was crossing over the vast Lansdowne Bank. On the north end of the bank, there is an area called Nereus Reef, where the water depth is only 12 feet deep in some places. Scallywag drew just over 15 feet. Every boat in the fleet was being tracked electronically, and Rick Tomlinson, the official observer on duty in the event’s race-control office, was monitoring their tracks. According to the international jury serving as the protest committee for the race, Tomlinson was “an employee of Volvo Ocean Race who, as a member of race control, has a responsibility for the safety of all competitors.”

Tomlinson noticed that Scallywag was on a collision course with Nereus Reef, so he emailed the boat’s navigator. “Just so I can relax a bit here in race control,” he wrote, “tell me you are happy with your course in relation to Nereus Reef on Lansdowne Bank.”

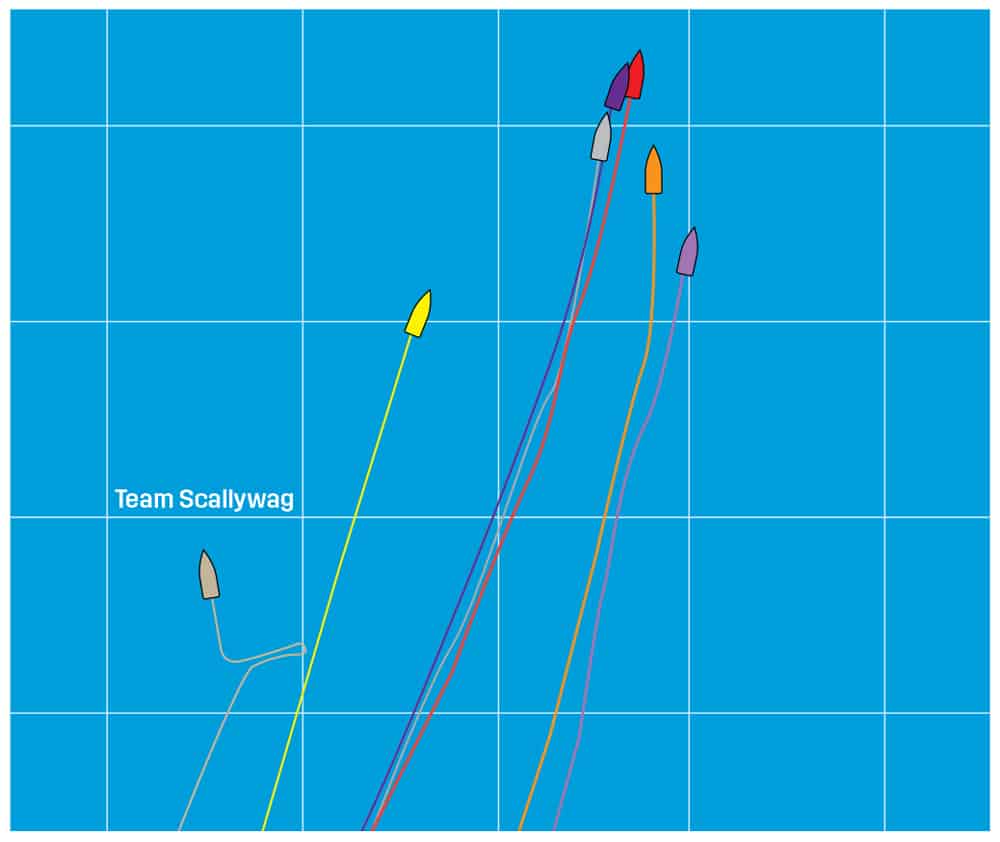

It’s interesting to watch the gyrations in Scallywag‘s track immediately after the boat received the message. Before receiving the email, it had been heading just east of north at 16 knots. At about 0800 UTC it bore off to the east and slowed to around 7 knots. An hour later, it had turned through south to a westerly course, and at 1120, it was back on its original course and speed. The race committee estimated that Scallywag lost 50 miles on the rest of the fleet during the time it was off course and sailing at reduced speed while working out a way around Nereus Reef.

The race committee was aware that when Scallywag acted in response to the committee’s email the committee was an outside source, and that it had provided assistance. Rule 41 (see box) prohibits a boat from receiving such help unless one of the four exceptions in rules 41(a), (b), (c) or (d) applies. An international jury had been appointed for the Volvo Ocean Race. Rule N2.1, which applies when there is an international jury for a race, states, “When asked by the organizing authority or the race committee, [the IJ] shall advise and assist them on any matter directly affecting the fairness of the competition.” The race committee took advantage of this rule to ask the jury, “[Did our email to Scallywag] constitute outside assistance under RRS 41 as the crew were in danger? Please would you consider and advise.” The international jury answered as follows:

“The jury advises that race control’s action did not result in a breach of Rule 41 by SHK Scallywag. SHK Scallywag did receive help from an outside source, in this case the race control. However, the help given is permitted under Rule 41(d). The information was not requested by SHK Scallywag, so it was unsolicited information. The source, in this case a member of the race control, was a disinterested source for the purposes of Rule 41 because he had no personal or other interest in the position of SHK Scallywag relative to other boats in the race. Nor would he gain or lose in any way as a result of the position of SHK Scallywag in the race.

“The source was an employee of Volvo Ocean Race who, as a member of race control, has a responsibility for the safety of all competitors. Asking the question he did was therefore a proper action for him to take.”

There were never any protests or requests for redress as a result of the help given to Scallywag. However, there was discussion among judges and online pundits. Everyone seemed to agree with the jury statements about Rule 41(d), but many were puzzled that the jury did not discuss Rule 41(a). The race committee had said in its request for advice that the crew of Scallywag was “in danger.” Rule 41(a) says that a boat may receive help “for a crewmember who is … in danger.” Therefore, the exception in Rule 41(a), as well as the exception in Rule 41(d), applied to Scallywag, but the jury only mentioned Rule 41(d). If exception 41(a) applied, then the last sentence of Rule 41 also applied. That last sentence allowed any boat, or the race committee or the protest committee, to protest Scallywag if it received “a significant advantage in the race from help received under Rule 41(a).”

Rule 41 Outside Help

A boat shall not receive help from any outside source, except

- (a) help for a crewmember who is ill, injured or in danger;

- (b) after a collision, help from the crew of the other vessel to get clear;

- (c) help in the form of information freely available to all boats;

- (d) unsolicited information from a disinterested source, which may be another boat in the same race.

However, a boat that gains a significant advantage in the race from help received under rule 41(a) may be protested and penalized; any penalty may be less than disqualification.

If a protest had been made, then the jury might have faced a very difficult task, with no precedent to my knowledge, determining what penalty “less than disqualification” to assess.

Let’s step away from the Scallywag incident for a moment and discuss how the words “or in danger” came to be included in Rule 41(a). For decades before 2013, the words “or in danger” were not in the rules about outside help.

This wording was added in 2013, and the story behind the rule change is an interesting one.

For decades, it had been permissible for a boat to receive outside help under Rule 41(a) for a member of the crew who is ill or injured. In 2013, that rule was expanded to also permit outside help for a crewmember “in danger.” The change came about following an incident several years ago at a world championship for Cadet class dinghies near Perth, Australia. A week before the first race, a swimmer was attacked and mauled by a great white shark in the waters where the championship was to be held. Rather than cancel the event, organizers arranged for additional safety boats to patrol the course and changed Rule 41(a) with a sailing instruction that permitted competitors to receive outside help when they were in danger. The kids were told that if they capsized or fell overboard, they would immediately receive help getting their boats up and themselves back in the boat, and they would then be permitted to continue in the race. Ultimately, there was never a need, but when World Sailing leadership found out about the rule change made at the event in Perth, it strongly supported including it in the 2013 rule book.

Not many of us will ever be in danger of shark attacks or running onto Nereus Reef in the Coral Sea, but we’ve probably all seen situations where a crewmember of a boat is in some danger, perhaps because he or she became separated from the boat, and then is helped out of danger by another boat in the race, an official boat or even a boat that just happens by and has no connection at all to the race. Before 2013, any boat that received help for a crewmember in danger broke the outside-help rule and was expected to retire from the race. That part of the outside-help rule often led to clashes between competitors and rescuers. When rescuers offered help, competitors, not wishing to have to retire from the race, would refuse to accept the help and try to get back aboard their boat unassisted and continue racing.

Since 2013, a crewmember in danger that is helped does not break Rule 41 and may continue in the race. The last sentence of current Rule 41 was also added in 2013. It was added because of concern that a situation like the one I will describe now would occur: Going into the last race of a series for Optimists, Abel and Cain are tied for first place. Whoever finishes ahead of the other will win the series. On the last leg, Abel and Cain are overlapped and battling each other when a squall hits the fleet, capsizing many boats, including Abel and Cain, who become separated from their Optis. They are “in danger” because the water is cold and hypothermia is a risk. Immediately after the squall passes, safety boats hurry to place sailors back in contact with their dinghies. Abel is helped a couple of minutes before Cain, so Abel finishes ahead of Cain and wins the series. This seems unfair, and it is for just such an incident. Thus, the last sentence of current Rule 41. It permits Cain to protest Abel and enables the protest committee to penalize Abel just enough to make the outcome fair, which in this case would mean creating a tie between Cain and Abel.

The discussion stimulated by the Scallywag incident has uncovered many ambiguities in Rule 41(a) and Rule 41’s last sentence. Here is a list: Did Scallywag “gain a significant advantage” from the help it received? The answer isn’t obvious. It was in last place when the email arrived, and the rest of the fleet advanced 50 miles before Scallywag was back on course. No advantage there. It would not have finished at all, however, if it had piled onto the reef and torn open its hull. That’s a significant disadvantage, for sure.

Suppose someone wanted to protest Scallywag. A protest is an allegation that a boat has broken a rule, and Rule 61.2 requires a protestor to identify that rule in writing. Scallywag did not break Rule 41 by receiving outside help because all of its crew were in danger. So what rule did Scallywag break? Rules under which protests are made state, or clearly imply (see, for example, Rule 42.2), that a boat “shall” or “shall not” do something. Rule 41’s last sentence does not make such a statement. So, a boat that receives help permitted by Rule 41(a) does not break Rule 41 or any other rule that I know of.

Rule 64.1 permits the protest committee to penalize only a boat that “has broken a rule and is not exonerated.” Scallywag, therefore, cannot be penalized even if the penalty the protest committee wanted to give was substantially less than disqualification. In the Abel and Cain incident, if Abel realized that by accepting help, he might be penalized, he would probably have refused to accept the help. The words “or in danger” were added to Rule 41(a) in order to avoid competitors refusing to accept help. So, the last sentence of Rule 41 works against the intent of the words that were added to Rule 41(a).

The bottom line: Rule 41 has several logical and practical problems. What should World Sailing do? I have discussed these issues with several experienced judges and sailors, and the consensus seems to be that the last sentence of Rule 41 should be deleted. This would mean that if an incident like the Abel and Cain one ever occurred, an unfair result would occur. But lots of “stuff” can happen to make the result of a sailboat race seem random or unfair. Until I learned of the Scallywag incident, I had never heard of the last sentence of Rule 41 ever being applied, so its deletion would be unlikely to result in many, if any, unfair outcomes.

Email if you know of a penalty that was given under Rule 41’s last sentence. I would be interested to hear your views on whether you think deleting Rule 41’s last sentence is a good idea.