To racing sailors everywhere, and particularly to California racing sailors, it must feel as if the sport is suddenly cursed, or suddenly more dangerous. It’s an understandable reaction. Just weeks after losing five sailors in the Crewed Farallones Race, word came this weekend that three sailors (and a fourth is still missing and presumed dead) were lost during the Newport-Ensenada Race. It wasn’t rough weather or navigational error. The Hunter 367 Aegean was simply obliterated in the dark of night near the Coronado Islands. The most likely cause: a large ship ran the Aegean down and continued on its way.

The first clues to the tragedy came the next morning, when safety patroller Eric Lamb came across debris scattered around the sea. It wasn’t long before three battered bodies were pulled from the water, and the search for the fourth crew was launched. The broken bits of boat were so small, and the dead sailors were so beaten up (with scrapes, bruises, and at least one severe head trauma), that Lamb said it looked as if the boat had gone through a blender.

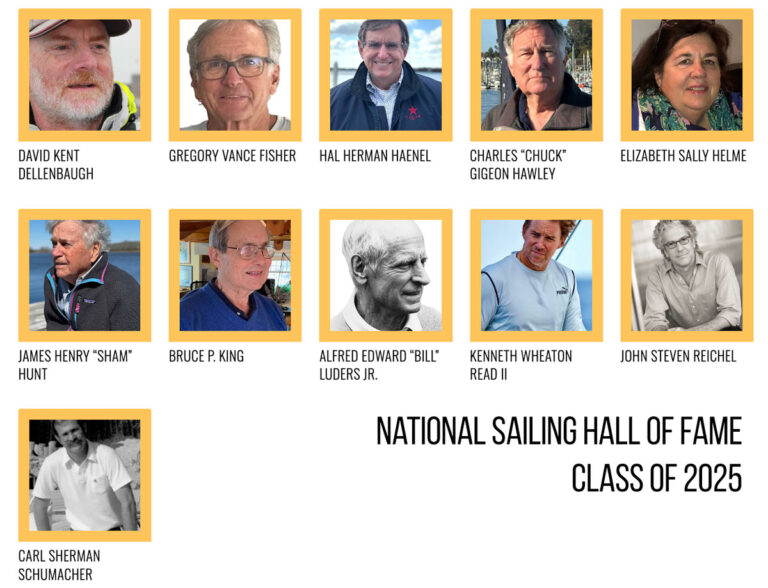

Aegean and its crew at the start of the Newport-Ensenada Race.

Any life lost at sea is a tragedy for family, friends, and the sport of sailing. And the natural reaction is to want to prevent the same thing from happening again. Already the Coast Guard in San Francisco, in the wake oaf the Farallones fatalities, has suspended ocean racing out of San Francisco, pending a safety review. And US Sailing President Gary Jobson said, in response to the Aegean‘s loss: “I’m horrified. I’ve done a lot of sailboat racing, and I’ve hit logs in the water, and I’ve seen a man go overboard, but this takes the whole thing to a new level. We need to take a step back and take a deep breath with what we’re doing. Something is going wrong here.”

Of course there are lessons to be learned, and Farallones survivor Bryan Chong started that conversation in a calm and thoughtful way with his account of what happened:

_It’s obvious to me now that I should have been clipped into the boat at every possible opportunity. Nevertheless, arguments for mobility and racing effectiveness over safety are not lost on me. Some safety measures can indeed limit maneuvers, but if you’re going to spend an hour driving, trimming or hiking in the same spot, why not clip in? Additionally, there are legitimate concerns about being crushed by the boat. Those 15 minutes in the water were the absolute scariest in my life. The boat was the place to be – inside or out.

_

The wrecked hull of_ Low Speed Chase _is flown home from the Farallones.

And there are still plenty of questions that need answering, especially with the Newport-Ensenada Race tragedy. Like what kind of awareness do merchant ship captains leaving San Diego have regarding large fleet races? What ship-alerting technologies, if any, did Aegean sail with? How many lookouts and crew on watch did the ship which struck Aegean have on the bridge? (It was almost certainly a ship and will very likely be identified through tracking records.) And many, many, more.

But it is important not to over-react to a cluster of deaths, or interpret them to mean that sailboat racing is suddenly becoming more risky. I am more surprised by how few deaths there are with so many sailors, of such varied experience, racing so many different types of boats, with different standards of maintenance and safety, across always unpredictable seas. Last year, according to Coast Guard statistics, there were 672 recreational boating deaths. How many occurred during sailboat races? Exactly two (on Wingnuts in the Chicago-Mackinac Race).

The number for 2012 is clearly spiking upward, but that is what time, probability, and the vicissitudes of nature do to numbers. There is no apparent common denominator in these recent deaths, other than bad luck. That doesn’t mean I think we should do nothing. By all means, look carefully at implementing some sort of offset mark system, or exclusion zone, for Farallones races. Think hard about tethering routines, and ship-alerting and lookout strategies. Every tragedy offers insight and wisdom, and every serious sailor should try to learn the lessons of each mishap. But I was already squeamish about the idea of suspending San Francisco ocean racing over an especially bad set of waves. Now I can feel media and (non-sailing) public criticism creating an environment that welcomes calls for new regulations and restrictions that could easily detract more than they add. (It is tempting to suggest that if you really want to dramatically reduce boating deaths, the single most important thing you could do would be to get boaters to stop peeing off the back of their boats.)

The simple fact is that while you can always keep learning how to sail smarter or safer (that’s why experience matters), sailboat racing has always been a test of human judgment in which knowledge, logic, and intuition are used to balance risk against reward. The sailors who strike the best balance usually win. And the more flexibility, latitude, and personal discretion you take away from racing sailors in that game of assessing risk and reward, the more you diminish and dumb down the game (while increasing its costs, I might add). So mourn the sailors lost in April 2012 (and look hard at how merchant ships maintain a lookout), but don’t let the sorrow of their loss undermine the sport they loved so much. If there is no real risk, there is no real reward. You can’t have one without the other.

Farallones survivor Bryan Chong, fresh from the loss of four crewmates, wrote: “A sailor’s mindset is no different from that of any other athlete who chooses to participate in a sport that has some risk. It’s a healthy addiction. . . We all make personal decisions about the risks we’re willing to take to enjoy our own brand of sailing.”

He could not have imagined that four more racing sailors would die soon after. But his words are true no matter whether sailors die in clusters or over time. And that’s important to remember as the safety investigations continue.