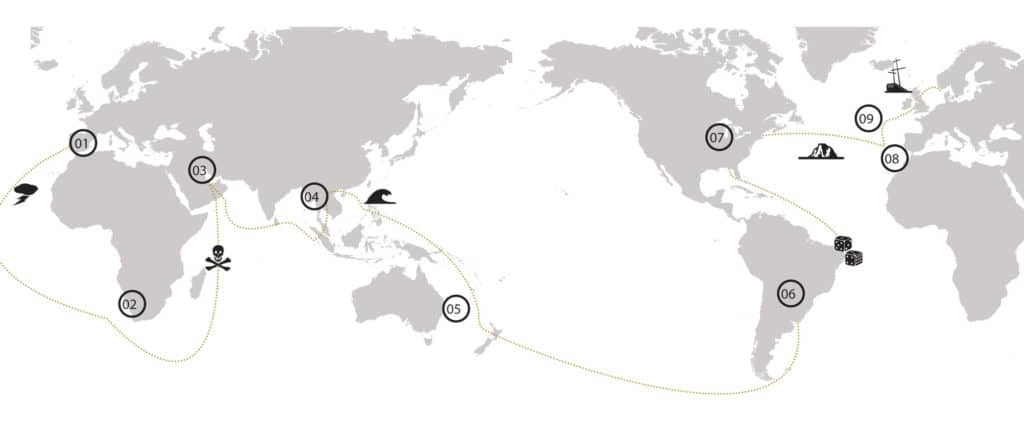

Our in-house Volvo Ocean Race navigator Wouter Verbraak explores the challenges of the 2014-’15 race route. No one ever said it would be easy.

01 – Alicante to Cape Town

The first leg won’t be huge waves or big storms. Instead, light winds, coastal twists, and squalls are all in the cards, leaving the sailors without much sleep for the first 48 hours. Exiting the Strait of Gibraltar in the lead is a getaway card. First to touch the northeast trade winds gets away. The most common strategy then is to head west for a good wind angle farther down the track.

The big obstacle is the Doldrums, notorious for powerful squalls and large windless holes. The shortest course is east, across a much wider windless area. Going too far west could result in beating upwind in the trades after the Equator. It is a balancing act, with a lot at stake.

The next hurdle is the St. Helena High and the exit ramp to the Southern Ocean’s speed-record alley.

02 – Cape Town to Abu Dhabi

With the threat of pirates diminished, the fleet will sail all the way into the Persian Gulf which, in December, has light winds from the Equator north.

Passage to the Equator is blocked by adverse winds. The strategy is to get east using the westerlies in the Southern Ocean to reach the ESE trades. Then comes the decision to leave the westerlies. Go early and have a shorter route, or invest in the east to get a better and much faster wind angle. The VO65s like the wider wind angles, so big gains can be made here. After the trades, the Indian Ocean Doldrums are next. They’re less defined than those in the Atlantic, but the squalls and holes can be destructive.

The stretch from the Equator to the entry of the Persian Gulf is light northerly winds. Tactically, this means there are a lot of options until the very end.

03 – Abu Dhabi to Sanya

Welcome to the northeast Monsoon season. The Monsoon is stronger in the east, so the boats will gradually sail into more and more breeze. Strong currents and squalls between India and Indonesia can be a real game changer, as was shown in the previous two editions of the race.

Then it’s into the tricky Straits of Malacca. Spring tides, no wind, sea breezes, ships, tree trunks—they are all part of the package. Typically this takes a day or two, and then there is no rest for the wicked, as the stretch through the Chinese Sea to Sanya is all upwind sailing. As the winds follows the contours of the land, the standard scenario is to play the left-hand side of the course, short tacking up the Vietnamese coast in 25 to 30 knots. Any takers?

04 – Sanya to Auckland

With the strong northeast Monsoon the dominant player, conditions are challenging. With the cold start in Sanya, the wind angle will be good; a fast and furious reach. But after this, the track to New Zealand takes them across the Doldrums at its worst. Investing in the east will take them well off course, so finding the right moment to get east will be key, and will mainly depend on finding a good wind angle to do so. Wait too long, and they might get trapped west. If they manage to get east, their hard work might pay off with a good angle in the east to southeast trade winds south of the Doldrums. Then it comes down to playing the high-pressure area best. The approach to Auckland is unpredictable: Sometimes inshore wins, sometimes the outside gets the end-around. Eyes open here: the fight is not over until you cross the line.

05 – Auckland to Itajai

Welcome to the proper Southern Ocean leg and Cape Horn rounding. The exit from Auckland is messy, with choices to be made to stay inshore or go offshore when sailing southeast along the New Zealand shore. Once clear of the mainland it’s crucial to set up for the first frontal passage. If timed right, they can ride the frontal wave for a long time at exhilarating speeds. Get it wrong and be ready to loose 500 miles overnight. While surfing the fronts to Cape Horn, the low-pressure systems slow down as they pile up between the Andes and the Antarctic Peninsula. Winds can be light if too far south.

Celebrate rounding Cape Horn after two weeks of cold misery, and then it’s a sunny game of getting north as best as you can.

06 – Itajai to Newport

This is leg is pure tropical reaching joy. Or is it? The bay between the Itajai and Rio de Janeiro is called the Bay of Death, and is dominated by light winds and strong counter currents. The challenge after the start is to get out of it and into solid winds to the east. A radical move can net big, but can turn quickly sour as well. The big decision is how far to stay off the Brazilian coast. Closer is shorter distance, but further offshore winds are typically 2 to 5 knots stronger, which makes a big difference.

After the Caribbean drag race things get complicated. The tradewinds decrease in strength, and turn to the south, resulting in a long light-air run north. Options, options. To make things even more complex, there’s the Gulf Stream and its many meanders. It’s the Bermuda Race in reverse—oh so tricky.

07 – Newport to Lisbon

Spring weather can still be very violent with intense low-pressure systems developing seemingly out of nowhere. Then there’s bound to be ‘bergs in the Labrador Current and more meanders in the Gulf Stream. Ahead of the fronts there are good strong southwest winds. Behind the front, winds typically get light quickly closer to the Azores High. So, like in the Southern Ocean, it’s all about positioning for the front and then milking the southwest winds for all they’re worth. The other strategic hurdle is how to play the curve of a slow moving Azores High. The Volvo 65s love the reaching angles, so any good windshift gets the jackpot. Big time.

08 – Lisbon to Lorient

Time to pay attention. The legs are shorter and the pace is going higher. These are the final minutes of the match. Overtime before the penalty shootout. Every shift counts. The devil is in the details.

So what to look out for? This leg will again be all about negotiating the Azores High, but now there’s the turning mark at its very center. Movement of the High is an unpredictable affair and calls for a conservative approach. Once around the Azores, it’s off to the Bay of Biscay and the French coast. Hopefully it will be a downhill ride all the way, surfing a cold front. Lows and their fronts tend to slow down as they approach Europe, throwing curve balls at will. Local effects are numerous and will be crucial for the final approach. Bon courage!

09 – Lorient to Gothenburg

Surely the last leg will be a straightforward reach to the finish, no? Afraid not. The Channel and North Sea are known for strong tides and unexpected changes in the wind pattern. With all the land around, the relatively stable weather systems of the Atlantic get jumbled, leaving an erratic wind pattern in their wake. Add to this coastal effects and sea breezes. No rest for the navigator.

So, it will be key to switch modes from ocean racing to coastal racing by playing more tactics and the smaller strategic points on the racecourse. Every detail and every boatlength counts. Oh, and do mind the rocks. Bricking up on one is not the way to finish a round-the-world extreme adventure.