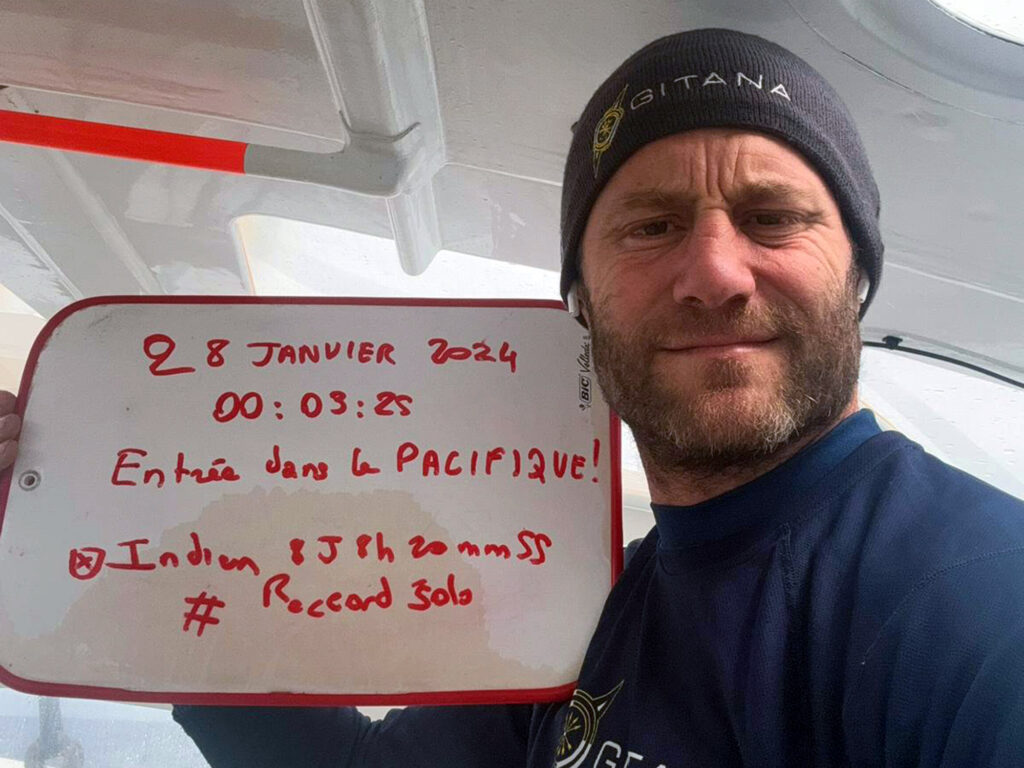

On his solo 50-day circumnavigation with a 100-foot foiling trimaran, Charles Caudrelier averaged 23.74 knots through the water and finished two days ahead of second place. The new speeds are so great, they shrink weather systems to the status of puffs on a pond. Be in the right place, get your puff, and you’re gone—with a few complications.

The faster you go, the harder you hit. Heading down the Atlantic, outbound from France, Caudrelier’s Gitana 17 was pushed hard in a neck-and-neck duel with up-and-comer Tom Laperche on SVR Lartigue. Even following from ashore, with just a touch of imagination, it was a breathtaking match. Then Laperche dashed/crashed/smashed head-on into an all-too-common UFO—unidentified floating object—and limped away to South Africa with too much damage to continue. “Could have happened to anybody,” Caudrelier mused. “When we started, we really didn’t know if we could do this.”

Of the six giants that blasted hell for leather across the starting line, five completed the Arkea Ultim Challenge Brest. All took damage, but Gitana’s only significant damage came in a nonstructural fairing kicked out of kilter by diving through a wave. Thomas Coville, second, sailing Sodebo, sat two days in Tasmania to repair his main bow pulpit and port trampoline, but that did not account for finishing two days behind the winner. Caudrelier caught the dream-ride puffs early and eventually built a cushion of thousands of miles. Had his lead been threatened, he might not have ducked into the Azores to wait out a depression lying across his route, threatening an otherwise sure victory. We can leave the rest to the what-ifs.

With one lap accomplished, the Ultim class is the new holy grail for the very-French fascination with ultimate speed and going solo. In these circles, that boat you learned to sail on and the one most readers sail now is known as Archimedean. With no disrespect intended for the Greek mathematician and physicist who developed our principles for calculating buoyancy, displacement boats in these circles are so five minutes ago.

Designers, engineers, and the brave souls who sail Ultims now are debating, running tests, and laying bets on a next generation of foils, sails, and new builds, all beyond human scale but as much a set of compromises as any boat. Big foils will lift a sailing craft into flying mode at low windspeeds. Advantage, big foils. As winds pick up, and boatspeed too, big foils become drag and a liability. Critical advantage to smaller foils, but how much smaller? And suddenly, heavy versus light enters the conversation as a complication.

When first launched, Gitana 17 was slow to the point of being a joke to insiders. The foils weren’t right, and “the boat was heavy. No one expected good things, and no one expected us to one day be racing around the world on foils,” Caudrelier says, remembering a time when he was not yet skippering Gitana. After his 50 days at sea on a revamped boat, Caudrelier speculated publicly that the next Gitana ought to be even heavier.

Whether that was information or misinformation, only time and new launches will tell. Though a lighter boat will take off sooner, once on its foils, a heavier boat might be more stable and capable of sailing deeper into high-wind ranges, or foil developments could render any such advantage moot. The design process is competitive and secretive, but the pieces of the puzzle are known.

The sailors to a man pronounce these foiling giants more comfortable and, yes, safer than previous oceangoing multihulls. The comfort comes from flying above waves rather than slamming into them.

Safety follows. “It’s like a suspension system in a car,” Caudrelier says. “We’re no longer constantly afraid of capsizing. The foils work together to stabilize the ride.” If that seems counterintuitive, consider that, unlike an America’s Cup foiler, the aim is to rarely if ever hit maximum speed. Caudrelier reported that, flat-out, he was using only 80 to 85 percent of the boat’s polars.

Xavier Guilbaud, of the VPLP design firm, responsible for SVR Lartigue, notes that sea state is less of a limiting factor with the hulls raised on foils. Instead, “wavelength is critical. Close waves are a problem, but if you’re climbing up and down ocean swells, even a wave height of 5 to 6 meters might be OK.”

Aerodynamics matter on deck, Guilbaud says: “Hydrodynamics matter on bottom because the boats are not fully flying. The trend is to fly the windward float, but the center hull might catch a wave and cough up spray.”

Meanwhile, you can almost but not quite set aside your mental images of speed-record challengers losing flow in the gas-bubble zone of cavitation and launching away to a crash landing. There were no such incidents in some 152,000 accumulated ocean miles of the Arkea Challenge. However, any burst of 50 knots or above is, shall we say, a thrill. With considerable understatement, Caudrelier observes: “You can lose directional control. Think of a modern car that holds the road so well and you feel safe, until something happens.”

Absent shape-shifting foils to adapt to different flow rates, foils are optimized for boatspeeds in the mid to high 30s. Cavitation is more of an endurance issue than a barrier. As the designer for the Edmond de Rothschild group that fields the racers named Gitana, Guillaume Verdier says that the damage to carbon-laminate foils from speeds above 40 knots make them look “like they were blasted with bullets.”

Minimizing cavitation damage is on everyone’s must-do list as existing boats are tweaked for their next outings. And although Caudrelier at one point suggested, or joked, that aerodynamics might take a back seat in development, Verdier isn’t buying that, not with apparent winds of 40 to 50 knots most of the time. On a quieter note, Verdier hints at factions on how tightly to control any rule-based particulars for the Ultims. “I’ve never been good in class meetings,” Verdier says. “If you restrict too many things, people will find stupid ways to get around the restrictions. If a class is open, you tend to not make stupid things.”

Verdier is a Paris native long since removed to the quieter reaches of Brittany, where he avoids office norms like a plague, enjoys a view of megalithic religious stones from his window, and ponders the path forward. He is enthusiastic about shore-based monitoring. He proselytizes the need for effective whale-avoidance systems. And he looks forward to races with boats accumulating energy as they sail, “to demonstrate that it is possible to go without fossil fuels at all.”

Speaking separately, Verdier, Guilbaud and Caudrelier each predict double-skinned mainsails, America’s Cup-style, as a next experiment. Guilbaud says: “While we have made big advances in appendages over the past six to seven years, sail plans have stayed pretty much the same for 15. Maybe it’s time for a smaller sail plan with the same power and a lower center of effort. Things are changing. There were people sitting on the sidelines, waiting to see how this race would go. Now they know.”

A smaller sail plan would make the boats easier to sail or less daunting, at least. Guilbaud was lucky enough to once cross the Atlantic aboard SVR Lartigue—among the design/build team, that’s a competitive position—and it was an eye-opener. He says: “Getting off the computer and onto the boat, I understand better how they live on board and cope with loads that are simply incredible. Every maneuver is a nightmare. It was difficult to reef or jibe with four people on the coffee grinders, but Caudrelier south of Australia had a day when he solo-jibed 15 or 16 times. I can’t imagine that. Charles says he was exhausted for three days.”

This is not about sailing for Everyman. The Arkea Ultim Challenge Brest and the Ultim fleet would not exist without sponsorship money, blessed with a fan base for the rocketmen of sail. Their course included boundaries for ice zones and animal habitats. Even the Southern Ocean was not wide open. Optimal sailing angles be hanged—the sailors had to thread a line through the wilderness and what was, even for veterans like nine-time circumnavigator and former record-holder Thomas Coville, one of the great adventures of their lives. Anthony Marchand, finishing in 64 days on Actual, last of the foil-equipped boats, spoke of “two months on a boat with alarms going off every five minutes, always listening on high alert.” Eric Peron, finishing in 66 days with the nonfoiling, thirdhand Adagio, reported the only near-capsize of the race, and he may have mentioned that he was “jealous” of the foilers.

For Caudrelier, the race and the win fulfilled a dream that he’d seized upon as a teenager, a dream that he clung to like a junkyard dog as he went through his young years sailing any boat he could, often with the legends but not as That Guy. He had a slow climb highlighted by a Route du Rhum win and a Volvo Ocean Race win, and now this. The husband and father turned 50 the day before he sailed across the Arkea finish line and joked about ducking out of birthday hoopla only to be greeted by cheering thousands when he hit the dock—star-struck dreaming teenagers included. With Gitana 18 in the works and his sights set on skippering an upgraded Gitana 17 next winter for a fully crewed attempt on the Jules Verne record, he is That Guy.