An asymmetric spinnaker only needs to work in reach mode, so it’s typically designed flatter than a symmetric spinnaker. Because the luff is always the luff and the leech always the leech, sail designers have the luxury of optimizing the shape for each. Hence the term “asymmetric spinnaker.” The asymmetric is always in reach mode with the wind flowing from luff to leech, whether truly reaching or, more commonly, jibing at angles to VMG reach downwind.

Because a traditional pole with a symmetric spinnaker can be eased forward or pulled aft, the trimmer can set the pole angle to the driver’s steering angle by adjusting it perpendicular to the wind. If the boat is sailing slightly higher or lower than optimum, the spinnaker trimmer can compensate. With an asymmetric, however, because the sprit comes straight out of the bow and that angle is fixed, steering to the perfect angle is the most important thing to have correct on the downwind leg.

The optimum sailing angle is about 90 degrees to the apparent wind in this reach-to-VMG downwind mode. The sail designer has a more accurate number that comes out of the design software; I think I recall something like 93.4 degrees, recently, though it can be different for different boats. For example, a foiling catamaran will have the apparent wind significantly forward because it’s going so fast. This exact number, however, is hard to measure while sailing and it isn’t what we sailors care about. We care how the boat feels and performs.

To get my steering angle in the ballpark, I first use the masthead fly to get the boat just a little higher than 90 degrees to the apparent wind. I start off a little high to make sure I don’t stall the boat. Then, I use the angle that the tack line comes off of the sprit. When it flies straight to leeward, it’s about right. If it’s forward of that, I’m likely too low, the boat is probably feeling slow, and there is not apparent wind pressure on the back of my neck. If it’s aft of that, I will likely be able to go a little lower while still keeping speed. The trimmer has a lot to say about the angle, too, based on how hard the sheet is tugging. Conversation between the trimmer and driver, along with constant feedback from the rest of the team on actual performance, is the only way to fine-tune this critical sailing angle.

The VMG driving angle is significantly different in different conditions. In light wind, jibing angles might be 90 degrees, but in strong winds it might be only 20 degrees. That’s a big difference. The interesting thing through the entire wind range—even though the jibing angles, and thus the angle to the true wind, is radically different—is that the apparent-wind angle basically remains at 90 degrees. In strong winds, the boat goes so much faster than in light breezes, so the boat’s velocity becomes a big component of the apparent-wind vector. Sea state has some effect on angle, too. If it’s choppy and the air is disturbed, the angle needs to be just a little tighter to keep moving. If the water is flat, a deeper sailing angle of just a few degrees might be achievable without a significant loss of speed.

The halyard needs to be pulled higher to keep the luff from sagging too much as the wind increases, and eased to keep it from getting too tight in light wind. The asymmetric is designed for a noticeable, but not extreme, sag in the luff. If the boat feels underpowered in chop, a little more sag will help give it some punch. Several marks on the halyard for different conditions will help get it close to the right spot right away.

Once on the correct sailing angle, trim to just the slightest curl. I find often trimmers sail with large amounts of curl, but this is a sign the sheet is too loose. Wind-tunnel results show that trimming to the first sign of curl yet minimizing the amount of that curl optimizes flow attachment to the back of the asymmetric. If it’s too tight, with no curl, flow separates early. Constant small changes in sheet tension to keep slight curl works the best.

Main trim is important, too. I like to set the vang so the top batten is just a little bit more open than parallel to the boom. The apparent-wind is further aft up top because the wind aloft is stronger and there is less re-direct from the spinnaker, so a little twist is required. Once the vang is about right, I like to ease the main until it just starts to luff, and then pull it in a little until the luff goes away. If in doubt, I over trim just a little because it seems OK—under-trimming is not fast. In heavier wind, I don’t like too much backwind, so I will trim it in until there is minimal bubble.

When first on a run leg, err on steering a little high and trimming tight. Tactically, this helps protect a lane, but more importantly gets the boat ripping fast right away. Speed before depth is essential because once the boat is going well, the apparent wind goes forward and the boat can go lower. If in doubt, stay high a little longer because going too deep and stalled is a disaster. Once too low, the boat slows significantly, and then the wind moves way aft and the boat has to head way up to get going again. When in doubt, no matter where I am in the leg, I err a little high and experiment down.

In very heavy air, the boat binds up and wipes out if sailed too high, so unlike light and medium wind, I err on sailing a bit low. Once comfortably established low, I test going a little higher to get the boat ripping while still under control. One way I like to visualize steering in these conditions is sailing with the mast vertical: Steering low in the puffs to follow the tip of the mast to leeward, and up in the lulls to follow the tip of the mast back to windward.

The apparent wind will move around quite a bit during puffs and lulls. The driver must be proactive with steering to keep the apparent wind at the approximately 90 degrees optimum angle. I try to anticipate by having our wind caller saying, “Puff in 3, 2, 1, puff!” or, just as important, “Lull in 3, 2, 1, lull!”

I try and stay just ahead of the apparent wind steering curve by changing course at around “1,” making the transition smooth and minimal. If I’m even a little late, I will end up having to make more aggressive helm movements. I know I’m out of sync if our trimmer is going through a lot of sheet. I know I have it right when the boat is smooth and accelerates forward and down in the puffs with minimal clicking sounds from the spin sheet ratchet.

The apparent wind changes much faster on light boats because they accelerate and decelerate so easily and with that, the apparent wind is constantly changing direction. Fortunately, these boats are also more nimble so there’s a lot of steering going on to keep it in the groove. Light boats are so much faster on a plane, so a lot of effort should be put into getting on a plane and staying there. The extra height to get on the plane is well worth it because once on it, the apparent wind goes forward and the boat goes low and fast.

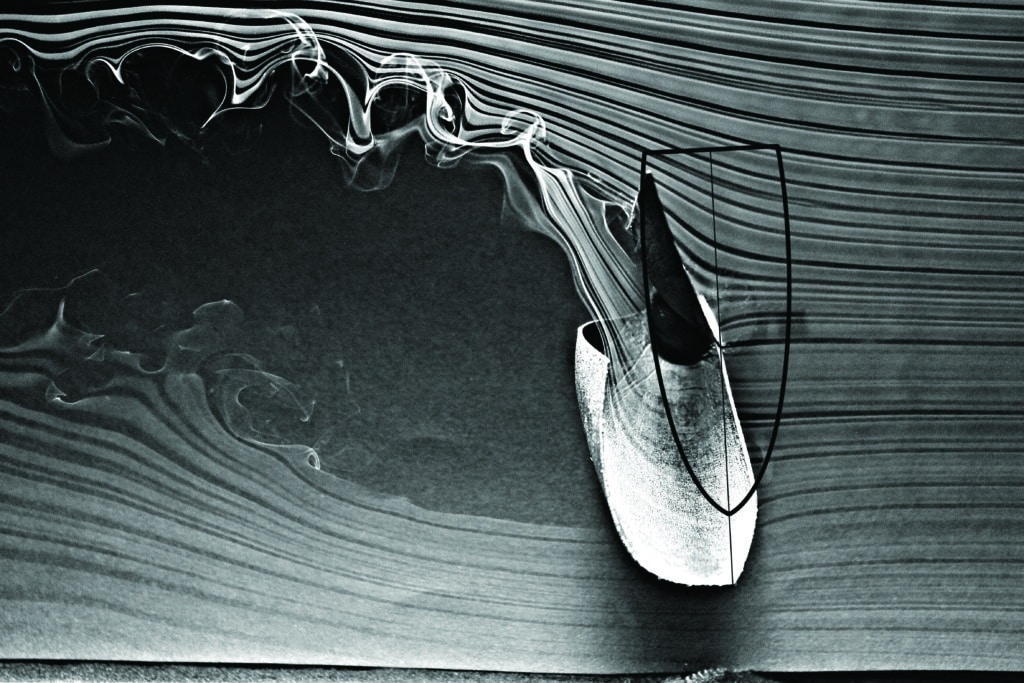

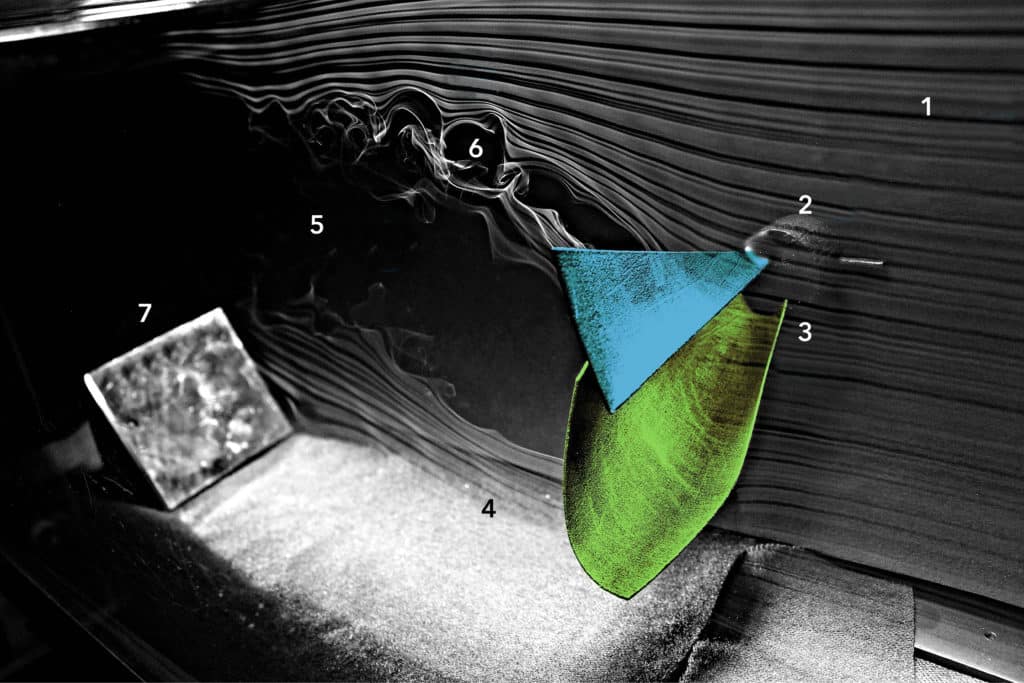

Observations from the Tunnel

- Smoke source: A horizontal line of smoke across both the spinnaker and mainsail.

- Model support: Fixture holds the 3D-printed mainsail and spinnaker in place.

- Entry: The wind enters here and flow is attached to both sides of the sails.

- Attach: Flow becomes attached to the leeward side of the spinnaker for about one-third of the area from luff to leech.

- Detach: Flow detaches here, and there is a significant wind shadow.

- Slot: Wind flows across the front side of the spinnaker, and attaches to the backside of the main.

- Mirror: This is part of the wind tunnel, used to illuminate the smoke on the back side of the sails where the light source is blocked.

Riley Schutt contributed to this story and conducted the wind-tunnel visualizations in the Cornell Fluid Dynamics Research Laboratories, where he is a PhD candidate of Professor Charles Williamson. Schutt has recently been a designer with Volvo Ocean Race and America’s Cup teams. Williamson is an avid Laser sailor. In the next issue, we’ll explore flow as it relates to symmetric spinnakers.