Ian Bruce’s death in late March, at age 83, caused me to reflect on the influence he and many other industry icons have had in shaping our sport. It’s only when we lose someone that we deeply consider his or her lasting contributions. In Bruce’s case, it was the Laser — nurtured from its meager beginnings to the 130,000 of them out there in 2016. Without Bruce, we would have no Laser. The same is true of the other Bruce — Kirby, that is. It’s hard to imagine what would stand today in the famous singlehander’s place if not for his and Ian Bruce’s influence. Yet rather than lay platitudes upon Bruce’s obituary, I thought it best to turn over this space to Kirby himself, to have him reflect on the life of a man who made it happen. Mr. Kirby, this space is yours once again.

Ian was the Jamaican-born son of a Myers’s Rum executive. When he was young, the family moved to the Bahamas, and he later relocated to Canada for his formal education. He attended Trinity College School in Toronto and then did two years of engineering at McGill University before taking a course in industrial design at Syracuse University.

He spent two years working in my hometown of Ottawa, where he married Barbara Brittain, whom my wife, Margo, and I had known since high school. Then Ian landed a job with a big Montreal industrial design firm, where he was approached by a marketing group that asked him for proposals for a line of outdoor sporting equipment. On the list was a “cartop sailboat.” Ian had a small shop near his home in Pointe Claire as a side business, and there he was building my Mark III International 14. We’d raced against each other in the 14 and Finn classes, so it was natural that he’d turn to me to design the “cartopper.”

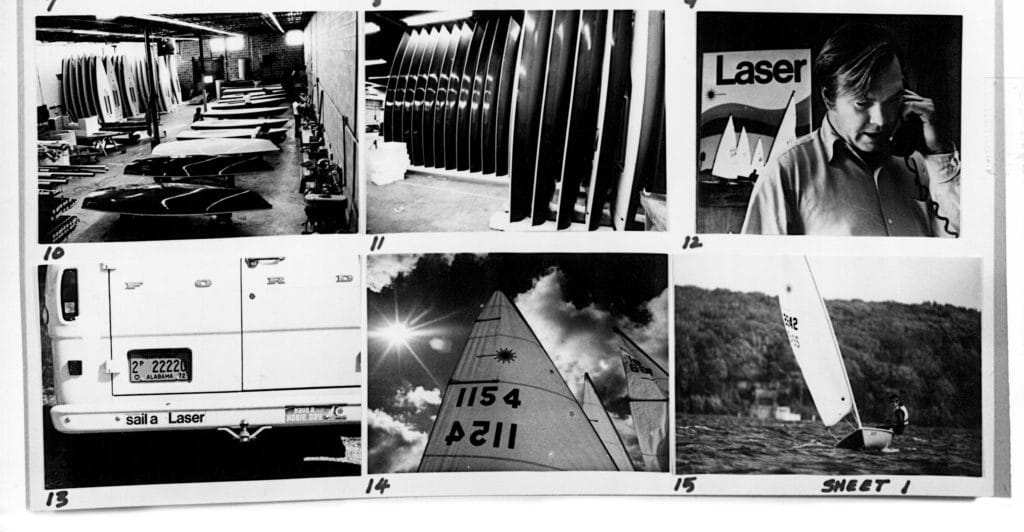

He had no background in marine design, and my experience was the designing of International 14s. At this time I was editor of One-Design & Offshore Yachtsman magazine, which is now Sailing World, and we had just moved our editorial offices from Chicago to Stamford, Connecticut. I was in my office overlooking Stamford Harbor when I got the call from Ian that changed both our lives and, thanks to him, the lives of tens of thousands of others. While we talked, I doodled a sketch on a yellow legal pad; it became known as the “million-dollar doodle.”

I took to the drawing board and calculator and worked for a few days drawing a full set of hull lines. Then came the profile and plan views, with daggerboard, rudder and cockpit, and finally the sail plan. The whole package was sent off to Ian’s home in Pointe Claire along with a note suggesting that if his client didn’t want a sailboat, he should put the plans away, as someday “we might make a buck on this boat.”

Sure enough, the marketing group passed on it, so the drawings went into Ian’s bottom drawer. Six months later, in April of 1970, our big break came. The advertising director of One-Design & Offshore hatched the America’s Tea Cup, a regatta for new and nearly new small boats. Monohulls had to retail for no more than $1,000 and multihulls for no more than $1,200. It would be held at the Playboy Club on Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, in October.

I called Ian and suggested this would be the perfect vehicle for introducing the new boat. His genius for making things happen came into play. He said he would build two prototypes. He had never built a boat from scratch, so despite herculean efforts, he barely got one boat finished in time for the Tea Cup. He popped hull and deck from their molds, glued them together, tossed the boat onto the top of his car along with the two-part mast, and headed to Lake Geneva. On his way through Toronto, he picked up Hans Fogh, who made the sail, and they drove deep into the night to get to Wisconsin on time.

The three of us put the boat together for the first time on the Playboy Club’s beach. It was a warm and windless day, and the scenery on that beach was seriously distracting. We’d been calling the boat the Weekender for want of a better name, and Hans had put “TGIF” on the sail. Hans was a silver medalist in the Flying Dutchman and also served as our test pilot. In the first race, he placed second to an adaptation of the Flying Junior hull. He was unhappy with the set of his sail, and that evening he re-cut the luff curve. The next day, the sail looked just right, and he won the first race by a hefty margin. He was leading in what was to be the final race, but it was called for lack of wind.

The boat caused a stir, and Ian was inundated with requests from dealers and buyers. He knew, however, that we had more work to do. So the Weekender went back atop the car and zoomed off to Pointe Claire. Hans and I were excited about the boat; Ian was ecstatic. His optimism and vivid imagination — hallmarks of his personality — could see that he had something special. It was a lively boat that might appeal to a broad spectrum of the sailing public.

For the next month, he was the point man for the empirical alterations to the boat. Hans and I worked on the sail plan, with me drawing three different sails, mailing them to Hans and phoning the new measurements to Ian. By this time he’d built a second prototype with an ingenious mast step that could move fore and aft as well as adjust rake. Working at an incredible pace during this time, Ian also settled a lot of small but important details, such as fittings, tiller length, and rudder rake, as well as vang specs. By mid-December of 1970, we had a final test weekend at Royal St. Lawrence YC, and were lucky to have a day of medium to light winds followed by a morning of 20 knots and sleet.

Ian, Hans and I put the boat through its paces, and Janet Bjorn, one of Canada’s best woman sailors, joined us with her fit 125 pounds to round out the test team.

The boat was ready, but we still didn’t have a name. That evening, the problem was solved when Dave Balfour, a student at McGill and a good I-14 sailor, suggested “Laser,” pointing out that it was a word understood internationally and one to which youngsters were becoming accustomed. Dave also pointed out that the laser logo, used in labs all over the world, would be perfect on the sail because it was symmetric and would therefore have to be put on only one side.

Ian then went into overdrive. He put a boat in the New York Boat Show in early January of 1971. There were 144 boats sold, which I believe is still a record. Dealers signed up and interest was beyond our most optimistic dreams. He got Canadian production up to 10 boats per day in a very short time. He licensed a factory in England, then one in California. Next came a big Irish operation. This factory helped the English plant meet the burgeoning Laser craze throughout Europe and into the Middle East.

Along with this rare talent to do the impossible, Ian was a fine sailor, even though he hadn’t found the sport until he was 20. He raced the Finn for Canada in the 1960 Olympics in Naples. In 1969 and in 1970, he won the Prince of Wales Cup for International 14s, sailing one of my Mark III hulls with an advanced flexible rig he’d developed himself. The boat was cold-molded in England, and Ian took the hull and put it into fiberglass production with a clever interior of his own design.

With the Laser operation running smoothly, he again made the Canadian Olympic team, in 1972, this time in the Star class, and sailed to seventh at Kiel, Germany, winning the final race. During the later part of his career, he brought three Australian-designed skiff classes into North America: the Tasar, 29er and 49er. Semiretired in 2010, he closed his sailboat business and developed a high-tech electric runabout, again putting a tremendous effort into development.

For one who came to the sport relatively late, Ian overcame the deficit with raw talent fortified by creativity and imagination. His mark on the boating world, and small sailboats in particular, is indelible.