As a round-the-world skipper, I spend 90 percent of my time managing the crew and their expectations. When I applied for the job of skipper for the Clipper Round the World Yacht Race, I was coming to the end of a 24-year career in the British Army. Those who volunteer for military service do so for a reason. This is also true of the paying crew of the Clipper Race. As a leader and motivator, if my crew wants to be there and do well, I’ve won the battle.

In the Clipper Race, skippers have a privileged position; we are highly trained and have seen most situations in which we’ll be sailing. Our charges hang on our every word and do exactly what we say. It is challenging to teach a new crew how the boat should run.

I always say to my Mission Performance “warriors” that every day is a school day. If you stop learning, you’re overconfident, which will lead to mistakes. I’m learning too, not just about sailing but also about boat management. This is healthy and keeps me grounded.

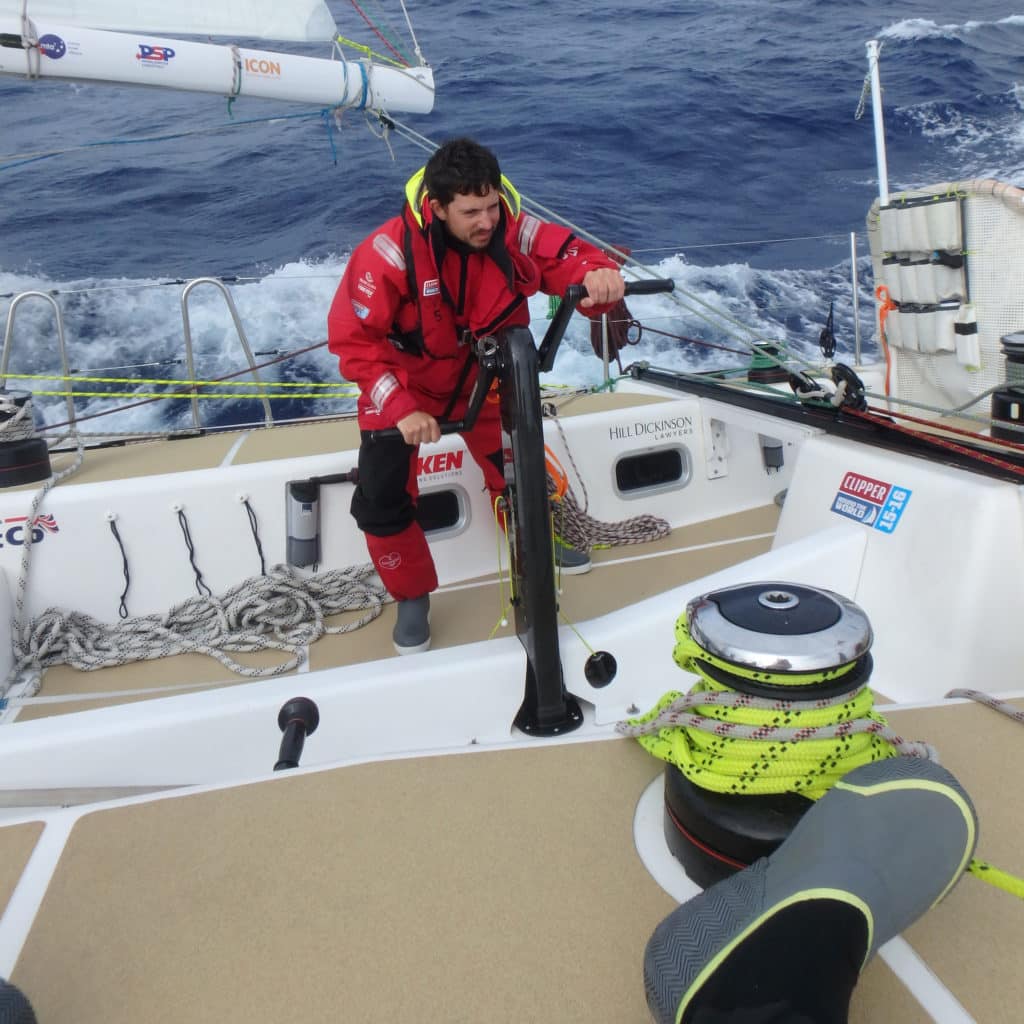

In London, before the race began, I adopted a coaching culture wherein anyone on board who knows how to do a task teaches others. This allows the crew to excel at everyday jobs, which in turn allows me to give them more control on board and make more decisions. Mission Performance is at the stage now where I have very little input in the day-to-day running of the yacht. It is amazing to see the progression that each of my sailors has made. My proudest moment was watching everything happen with little input from me during the race start at Albany, Australia. We had a short round-the-cans course before heading offshore. This included a spinnaker hoist and a number of jibes, followed by a headsail hoist and drop, all in a short time.

We had the added complication of one of our primary winches seizing. With no hesitation, watch leader Mike Moore sprang into action, moving the mainsheet onto one of the traveler winches, allowing us to adjust the sheet and take the primary winch apart to rectify the problem. This was all done within three minutes, with no fuss and very little chat. What could have been a game-stopper was remedied. All I had to do was concentrate on the marks.

During Leg Three, from Cape Town to Albany, I went nearly 48 hours without sleep. I felt I had to stay awake because we were close to the end of the Ocean Sprint section of the course, which would earn us bonus points in the overall tally. The wind was due to change both direction and speed, so tactical decisions were required. But I eventually relented to sleep, and the crew made the right calls, ensuring we remained competitive for that Ocean Sprint. As the wind came around behind us, the watch leaders went straight into spinnaker mode. Earlier in the race, such a decision would never have been made without my input, and I would have had to be on deck to ensure that it happened smoothly.

My warriors are not perfect and still make mistakes, but we are all only human. They can, however, make decisions, which wouldn’t have been possible at the beginning of the race. While I sometimes feel a little sad that I’m not relied on as heavily as I once was, I’m proud of what the team has achieved.