AC72 Daggerboard Hydraulics

All is relatively quiet along San Francisco’s Embarcadero waterfront on the eve of the 34th America’s Cup. The sailors have retreated to their bases and homes for the final hours of pre-race isolation and focus. The mood of yesterday’s opening press conference confirmed the high tension that exists between the two camps—as it should—and for the moment, the public jawing has hushed; actions will speak tomorrow at 1:10 p.m. PST.

Yet, still, the rumor mill turns, the latest now focused on Oracle Team USA’s daggerboard adjustment system and whether it complies with AC72’s rule concerning stored energy. Could their ability to foil as well as Emirates Team New Zealand be compromised? Some here say, “maybe.”

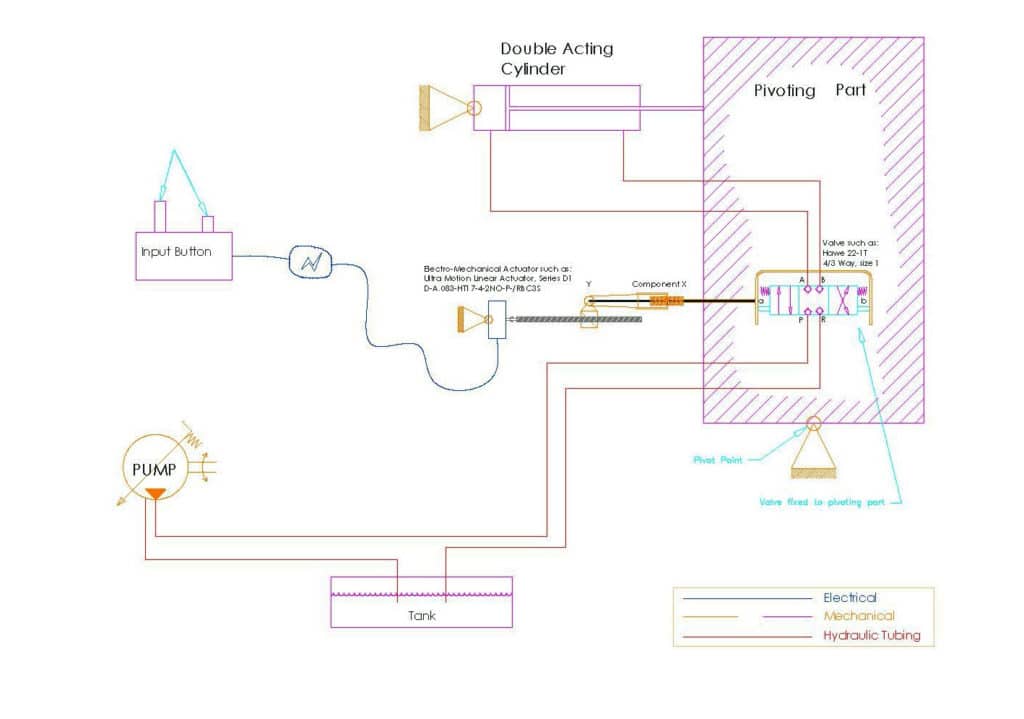

Since early August “Public Interpretations” have been sought on multiple occasions, seeking confirmation from the AC measurement committee that an element (“Component X”) of its hypercritical daggerboard system does in fact comply with the AC72 Class Rule.

In Public Interpretation No. 52 they ask, “The measurement committee have interpreted the hydraulic arrangement shown in PI 49 (see photo) as class rule 19.2(e) compliant, subject to measurement committee approval of the valve.

In PI 52 answer (4), the measurement committee further interpreted that the actuator as shown in PI 49 could compress the component between the actuator and the valve without the valve moving. During this operation the actuator will apply force to the pivoting part.

1. Can the force applied by an electrically operated linear actuator be used to adjust rigging, wing, soft sails, rudders and daggerboards?

To which the measurement committee responded, “No.”

“With specific reference to the diagram in PI 49, any springs or similar devices between the actuator and valve shall be small in nature and shall not be arranged to circumvent the prohibition on the use of non-manual power.”

Both ETNZ’s and Oracle’s boat have measured in, so whatever the system is today, it’s been deemed compliant. The issue, however, speaks to the importance of the daggerboard controls and the complex and sophisticated hydraulic systems required to maintain ride height, and precision through maneuvers. In July I spoke with Harken USA’s Mark Wiss, who is intimately involved with the development of hydraulic systems on the AC72s [Harken is providing and developing hydraulic, winch and hardware systems for Oracle Team USA]. At the time, Wiss stressed the importance of the AC72’s hydraulic package: more so than the wing.

The AC72 rule does not allow engines on the boat as we saw in the 33rd edition. Everything has to be manually driven, so to get enough oil flowing through the boat they use rotary pumps, which are linked to the pedestal grinders. The grinders are essentially pushing oil throughout the system the entire race. Any time they want a hydraulic cylinder to move—whether it’s in the wing or in the daggerboard system, a headstay, or jib cunningham, it needs oil.

“On these boats you turn the handle and move an incredible amount of oil very quickly to whatever you want it to do,” says Wiss. “So the heart of the hydraulic system is driven around the rotary pump. The team with the best, most efficient pumps can do more and faster with their hydraulic systems.”

The heaviest demand on the hydraulic system is the foil controls. The daggerboards can be adjusted by changing cant, lift, and pitch, although up and down is essentially only allowed for maneuvers. Once they’re up on the foil, controlling the daggerboard requires subtle, quick adjustments to prevent pitchpoling and maintain balance. “In order for them to work you need oil flowing to them, and the grinders working the rotary pumps,” says Wiss. “Usually you can have stored energy in an accumulator tank, which stores high pressure and you use it when you want, but that’s stored energy, and that’s not allowed under the rules.”

So it has to be oil on demand.

One thing that helps minimize amount of tubing in the boat is AC72 Rule No. 19, which deals specifically with stored energy. “The traditional exceptions to stored energy [in past Cups] were, for example, a battery for bilge pump and your computers, shock cords, springs for winches and hydraulic cylinders that put compressed air into the cylinder, which helps return it when you want to release the valve,” says Wiss. “Those have always been traditional exceptions to the stored energy rule. What they did this time was allow two exceptions; one was focused on winch systems, to allow electric control disconnections and clutches—these replace the traditional pedestal foot buttons. [The other] is specifically with hydraulics. They allow valves to be electrically driven.”

The components have to be commercially available. “We developed a system that can be used by any of the teams. It’s a system that uses electric servo motors that activate the valves,” says Wiss. “Being a catamaran, in order to centralize and reduce the weight in piping, you can centralize all the valves and manifolds in one area of the boat and then run electric switches wherever you want on the boat.”

The hydraulic systems are the absolute heart of making these boats go, he adds. “Without them, they would not be able to be doing what they’re doing. In order to jibe on the foils the hydraulic system has to be running perfectly. These systems are precision. They’re running at extreme high pressures, much more than traditional applications.”