As American Magic towed its AC75 Patriot to the racecourse on the afternoon of January 29, everyone with a hand and heart in the New York YC’s 36th America’s Cup campaign knew the situation was dire. They were already down two races to Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli in the best-of-seven Prada Cup semifinal eliminations, their beloved Patriot had been to hell and back, and the Italians were on a roll.

Cue the sporting cliches: chins high, game faces on, business as usual, one race at time. Win one and live to fight another day.

But no amount of positive spin from within the organization could change the fact that the boat was not the finely tuned racing machine it was before it capsized and sank on January 17. Gremlins were lurking inside Patriot’s dark blue hull, and so it was no surprise when the boat started acting up during pre-race warmup laps for Race 3 of the series. The American Magic support RIB pulled alongside and sent technicians through a watertight hatch in the deck to troubleshoot the boat’s foil-cant system. With the scheduled race start fast approaching, they emerged, sealed the hatch, and hoped for the best. Everyone on board knew the boat’s mechatronics weren’t right—not as right as they needed to be when facing an aggressive and confident opponent. Indeed, before Patriot even entered the starting box for Race 3 of the semis, fear of an FCS failure was very real. It would end the day, and the campaign.

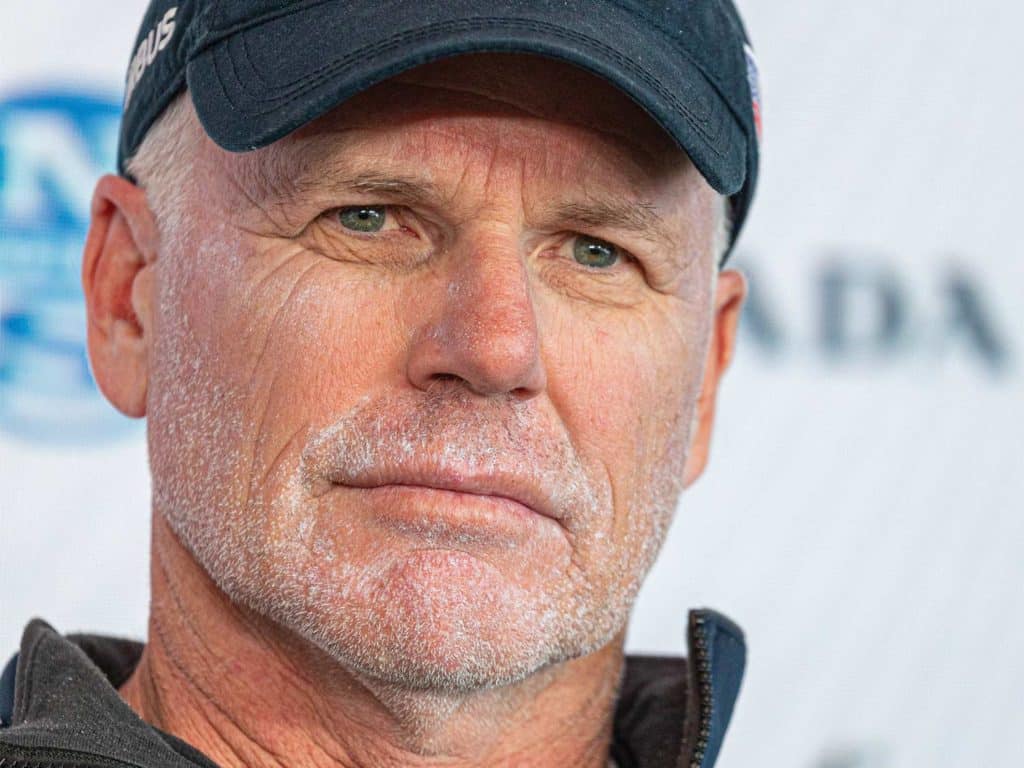

“We all knew what the scorecard was,” says American Magic CEO, skipper and tactician Terry Hutchinson, and from the recon they’d done, they were confident Luna Rossa would be “very well-disciplined to their timings, and they were.”

The Italians, of course, were eager to put a swift end to the series and get on with the business of developing their boat for the Prada Cup finals against Ineos Team UK in mid-February, the last hurdle before the Cup Match. Race-management software hiccups that had been nagging Luna Rossa in earlier races were nonexistent. This time, they entered the starting box on port and on time.

“It was a strong right-side call,” Hutchinson says. “Plan A was to start right. Plan B was to be as tight to leeward as we could.”

With perfect timing and execution, however, the Italians denied Hutchinson Plan A.

“Still, we got a good start to leeward, got to the boundary, tacked, and the breeze went 9 degrees to the right.”

Luna Rossa starboard helmsman Jimmy Spithill stuck a perfect leebow tack, and within seconds of powering their sails, the Italians were higher and faster. The moment Luna Rossa’s port helmsman Francesco Bruni looked over his shoulder to see Patriot tacking away, he knew he had control of the race.

And that was the end of that.

Both entered the next start, Race 4, on time, but in the final windup, American Magic turned back too early, and the Italians sailed over the top of them, blitzing the port end of the starting line. The Americans tacked across the line and set up an early split, but with stronger winds now on the left side of the course, the Italians streaked away to an early lead once again. Luna Rossa commanded the first cross, but the Americans were quick, eating into their lead and pushing them hard, fueled by a heart-racing cocktail of hope and dogged determination.

“The way the beat was setting up, we were going to go around the correct gate at the top and bear away into a strong spot,” Hutchinson says.

But then, it happened. Nearing the top of the course, less than 10 seconds from tacking on the port layline, helmsman Dean Barker counted down: “Two, one, board down…board’s not going here…board won’t go down…ah.”

It did eventually go down after a few more frantic button pushes, but after threading their way back through the weather gate and forcing the foil down again in order to jibe, Hutchinson noted aloud over his headset: “The lights are flickering kinda funny.”

“We did have a backup system installed, and it was working properly because we had battery shutdowns earlier in the day,” Hutchinson says. But this one final foil-control-system misfire wasn’t a battery issue, it was a command issue. “If you hit the button and it doesn’t take the command, then there’s a gremlin in the system. The gremlin gets sorted out only by having a technician hop on board to look at the data and solve the issue.”

They completed the race in the distant shadow of Luna Rossa, which made for an agonizing end to a brutally short campaign. The sudden ending to an effort with so much potential—a campaign cut short by one shocking and destructive sinking.

Hutchinson says it would be a gross simplification to point to the one final foil-control-system failure as the reason for the team’s early exit from the Prada Cup. It’s impossible, he says, not to connect it back to the capsize, and the obvious effects of putting the boat underwater for three hours. The brevity of the Prada Cup format is perhaps equally harsh. Three and a half years in the making, over and done in 10 races—without a single point in the win column. The word most often heard in post-race interviews was “potential.” American Magic, the top-ranked challenger going into the series, had plenty of it, and they were confident that they had a fast boat. But they never gave themselves the opportunity to prove it. They left more than just points on the racecourse—they left a multimillion-dollar campaign unfulfilled.

Once Patriot 2.0 was relaunched following the capsize and rebuild two days before the semifinals, they only had roughly six hours of sea trials, squashing gremlins the entire time. “We weren’t in the spot we wanted to be—and not through lack of effort,” Hutchinson says. For Race 1 of the semifinals, they had to shake off the capsize and get back into their race-day routine. They pulled off the dock on time, and it was blowing 24 to 28 knots when they got to the racecourse. “We sat there for an hour waiting to hoist because it was too windy. We couldn’t risk any further damage to the boat because of a battery shut-off or any one of the other issues we were facing.”

They’d mapped out their race strategy in the simulator that morning and felt confident going into the day’s first race. But that plan quickly unraveled.

“We entered in a 25-knot puff,” Hutchinson says. “It’s hard to turn the boat downwind when you’re going 51 knots. There was a lot going on, and we quickly got out of position. Luna Rossa is too good to put ourselves in a bad spot and not have them take advantage of it. And that’s what they did.”

In the following start, Race 2 of the series, he says, Patriot was in a good position in the first 20 seconds or so. “We came up behind them and went to tack to windward, but when we trimmed up, we couldn’t get the windward board out of the water…and that had an impact on the timing of the turn. When each position is mapped out almost to the second in the prestart, if there’s something that doesn’t go perfectly right, you end up late. We spotted them some distance, and they sailed away from us.”

They also had a case of the slows. In that evening’s debrief, Hutchinson says, they identified that they were sailing the boat at only 85 percent of what they normally would. “We should have been able to get the boat going properly, but the releases were going off on the hydraulics on the mainsheet and the cunningham. Everything is tuned to a certain pressure, and when you exceed that pressure, it releases so you don’t break anything. We kept running into releases on the mainsheet and certain things. We’ve sailed enough to know that when the boat is locked in, nothing is overloaded. And here it was overloading. [The boat] was cranky, and it was hard to sail.”

Patriot never behaved in this way before the capsize, an incident that has since been thoroughly dissected by the team and armchair experts around the world. American Magic mainsail trimmer Paul Goodison acknowledges that he would’ve preferred a different maneuver at the time but told reporter Ed Gorman that there’s no reason to second-guess what happens in the heat of the moment.

“I guess I felt that we had a big enough lead just to make things easy and get around the course. Dean obviously thought it was the right thing to do (tack/bear away) to keep racing and keep pushing and go the other way. If we had pulled off that maneuver, nothing would have ever been said about this. It’s just one of those things. Whether the campaign changed or moved because of those actions…”—Goodison pauses—”It is what it is, and that’s the past. There was no apportioning blame at one individual or a group of individuals, and what impressed me about all the sailing team is that nobody really mentioned it again. We had the debrief, we aired our thoughts, and then we just focused on getting back into racing and how we would get the boat around the course [in the semifinal].”

Reflecting on the day of the capsize, Hutchinson says, everyone inside the team was feeling the disappointment of being 0-3, but they were excited to race against Luna Rossa in a real breeze. “We did exactly what we thought we would do,” Hutchinson says. “We sailed away from them—because Patriot is a great boat.”

When American Magic rounded the leeward mark to start the final upwind leg of the race that fateful day, there was only 9 knots of wind blowing across the racecourse. A thunderstorm over the city was touching the bottom of the course, Hutchinson says, creating a big hole of no wind. “[Because of previous races,] we were pretty nervous about sailing into no wind and the associated risk of being in light air while the other guy is sailing at 18 knots. By the time we got about halfway up, it was up to 13 knots, and at about 20 seconds out from the mark, the breeze spiked to 18 and went really hard left. Ripping into the top mark at 45 knots…there’s a reasonable amount of hair on fire in those types of situations.”

Even after rewatching video of the maneuver ad nauseam, Hutchinson remains firm that the right maneuver was the same one they’d done on the previous leg: a tack and bear away. That one went smoothly in 16 knots of wind—just like they’d practiced—but as they turned past the mark and toward the finish, the wind spiked from 18 to 24 knots, and over she went after soaring through the air.

“We did a good job turning down, getting the board out of the water to create maximum stability, and committing to the turn—and that’s what you have to do,” Hutchinson says. “The one thing we didn’t expect was for the breeze to go to 24 knots in a three-second window.”

The team’s coach, James Lyne, watched the capsize from a chase boat. “The big thing with these boats is heel angle,” Lyne says. “You get to a certain heel angle, and you’re pretty much toast. If you come out of a maneuver relatively slow, the heel comes on, and it’s hard to control because the heel reduces your effective cant, and your righting moment goes away. When the rudder starts to ventilate, you get into a bow-up attitude, and the angle of the main foil wants to launch the boat straight out of the water. It’s never a pretty moment when you get to a sort of heel criticality coming out of any maneuver. These boats have quite a bit of inertia when they’re accelerating. There’s a point when there’s brace-brace-brace rather than trying to save it. There is a point where you’re along for the ride.”

Hutchinson says they’d sailed their first AC75, Defiant, in 29 knots of wind, in conditions well above the racing wind range, so this was not new territory. “We needed to do that to give ourselves confidence we could do it when we needed to in a race,” he says. “When we do a maneuver like we did, we’re not doing it without confidence. The timing of the breeze going from 18 to 24 knots through the maneuver—that’s a reasonably big deal, but we were racing and reacting.”

It wasn’t necessarily the capsize itself that drove a stake through the heart of the boat. The AC75 is designed to survive a tip‑over and to be expeditiously righted. What they are not engineered for is the explosive and destructive forces of a crash landing the likes that Patriot experienced.

“Was the capsize the ending?” Hutchinson asks. “Nope. I would say it wasn’t the fact that we capsized. It was that we blew a hole in the boat. The knock-on effect was of massive consequence. But the line of accountability comes back to those of us racing the boat, and in these situations, we have to keep pressing the boat hard and keep racing. People who criticize and think they are experts need to understand there are only 72 sailors on the planet who have an understanding of what an AC75 can and cannot do.”

And only those who witnessed the miracles that occurred inside the American Magic compound in Auckland after the sinking can truly appreciate the Herculean task that followed. “From the moment we capsized and incurred the damage that we did, there was a switch in the program,” Hutchinson says. “What became apparent to the outside world was the strength of American Magic. What they—the shore team, design team and production team—achieved over that eight-day window to get us out on the water was nothing short of miraculous.”

Everything had to be stripped from inside the boat, Lyne says. “These things take 12 months to build and so many man-hours, and we replaced a sizable percentage of the hull shell—all the internal structure forward of the mast, and then the system guys rewired and replumbed the entire boat. What might take six weeks they did in 10 days in the end.”

Given the extent of Patriot’s rebuild, it’s another miracle the boat actually weighed and measured for its semifinal races, further testament to the effort that went on 24/7 inside the American Magic boat shed. To be able to sail again was truly remarkable, and that, Hutchinson says, is what still stings the most. He can’t shake the remorse he feels for letting down his builders and technicians with a winless scorecard.

While the whole of the American Magic team fought to “restart the heart” of Patriot, the Italians focused intensely on developing themselves and their boat into a faster and more cohesive sailing unit, to which the Americans would have no answer.

“The key component we gave to our competition at the most critical moment was time on the water,” Hutchinson says. “It could not have happened at a worse time.”

“The biggest thing in this game is how quickly development happens,” Lyne says. “Even though you think you’re going forward, other teams might be moving forward at a faster rate. You don’t know when the leapfrogs will happen because yours might be coming in the next iteration in systems, how you sail the boat, or a physical piece of gear. There is no doubt we were moving forward. In the race against Luna Rossa with the capsize, the boat was pretty slippery in uprange conditions. We had a speed advantage upwind and downwind.”

Although Hutchinson refuses to do so, he could take solace in the old saying that you’re only as good as your last race. In those seconds before the capsize, Patriot was the quickest AC75 of the fleet, and there was supposed to be much more racing and development to come. So much potential. Eliminated so soon. So brutally.

“I am sure we will be unfairly scored in the score book in terms of our race wins,” Lyne says. “But in terms of what we did that day and in the days that followed, and what the other teams did through the rescue and rebuild, is one of the biggest things for the sport. Probably, in some ways, it could be transformational for the yacht club. That’s American Magic’s biggest story—not giving in, and showing resilience. The legacy we have after this Cup is quite a big one versus the scoreboard.”

Hutchinson, of course, would love to have another crack at the Cup, and so too would enough brass at the New York YC to make it a possibility. “When it comes to a screeching halt in the manner it did for us…” Hutchinson says before pausing to compose himself. “We were prepared for a lot of things, but we were never prepared for the manner in which it ended.”

It’s brutal, he says again. But no one ever said the America’s Cup was anything else.