Seven minutes after the start of Chicago YC’s Race to Mackinac, I’m soaked to the bone, my heart is pounding, and I can’t believe I’m sailing this damn race again. This is my sixth Mac, and each has served up some new form of terror. But there’s a lot riding on this one.

On this same weekend 100 years ago, my great-grandfather John O’Rourke passed through what was then called the Van Buren Street breakwater gap, along with 16 other boats, to attempt the Race to Mackinac. Much of what I know about him and his little Q boat, Intruder, I learned from the Chicago Tribune archives. Headlines like, “Intruder Fights Waves, Rain to Capture Mackinac Race,” had conjured a legend. And here I am on the bow of Skye, a Nelson/Marek 46, making my own epic journey to the island a century later.

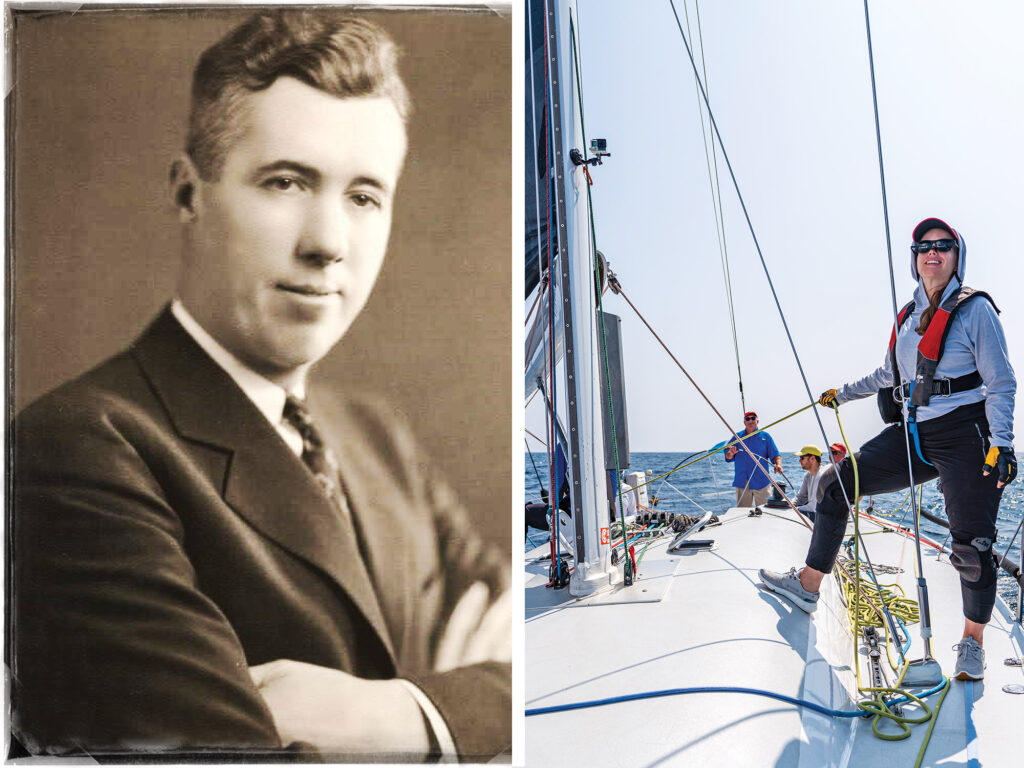

The skies open the moment we cross the starting line east of Navy Pier on the afternoon of Saturday, July 22, 2023. I am tossed around on the bow during our first spinnaker hoist, white-knuckling the lifelines as rain stings my face. Throughout the day, we navigate storms rumbling off the Wisconsin shoreline bringing windshifts and cold air. During the occasional lull, my thoughts drift back to John Paul O’Rourke’s 100-year-old logs full of notes on Lake Michigan’s unpredictable weather patterns and his calculations using celestial navigation. In 1923, at the age of 30, he was a skilled sailor helming a small boat he had purchased for $1,800 earlier that spring in New Orleans. Despite his inexperience with the vessel, he was confident enough to bet on himself. John and his fellow Mac skippers were gamblers and had pooled a cash purse for the winner. First prize for that year’s Mac was $600—one-third of the cost of Intruder. The Mac race committee has since banned this practice as a result of controversies surrounding the contested outcome of the 1923 race.

Today, while no cash is on the table, we have a little gentlemen’s wager tradition aboard Skye. Before we leave the dock, each crewmember bets on the number of sail changes it will take us to reach the island. As we cast off from Columbia YC’s dock, the predictions range from 12 to 35 sail changes, with the optimistic afterguard at the lower end and the pragmatic foredeck crew submitting the highest guesses.

By 17:27 Saturday evening, four hours and seven minutes into our 331-nautical-mile race, we are at 13 sail changes and making 7 knots on a run due north. I see 1,000-yard stares on the faces of our trimmers, Alex Loch and Tom Grant, as we notice a long cloud forming that looks like a gnarled finger pointing at us from the southern sky. Last year, similar clouds formed just before our anemometer spiked and a squall hammered the boat. Skye’s co-owner Jeff Hoswell expertly manned the helm while Loch, Grant, and I suddenly had to wrestle the jib to the deck in 38 knots and 8-foot waves. Low-side heroics from our pit, Dan Gardiner, are the sole reason we didn’t end up in the drink. In 2022, two nights of intense squalls left us beaten up and exhausted. While this night is not as sporty, it feels as though Lake Michigan might test us again at any moment.

The Skye crew was haunted by our last Mac. And 100 years ago, my great-grandfather was likewise haunted by his. The only other Mac he had participated in was in 1921. The race had taken a hiatus during World War I, and the size of the fleet dwindled. Chicago YC members launched a campaign to encourage younger sailors, often with smaller boats, to enter the Mac Race.

John O’Rourke and his brother James were among the newly invited competitors, on their boat, Chaperon. Their log from that 1921 race ends dripping with frustration: “Monday. 2:00 P.M. jibed spinnaker and also tore it. 2:54:49 P.M. Finished. Virginia finished 1:42:28. Chaperon’s allowance 1:10:14. Lost race by 2 minutes, 7 seconds.”

John didn’t celebrate earning second place in his first Mac attempt. “Lost race” offers a glimpse into his competitive fervor. He entered the race again in 1923, this time with a better boat, more experience, and a vow to beat Virginia.

Today on the deck of Skye, we use the waning daylight to check the positions of our own section rivals. At nightfall, the fleet is tightly packed on the rhumb line as stars appear over silhouettes of spinnakers. The crew trade in red caps and sunglasses for headlamps and tethers. At 20:00, we are tracking a menacing storm cell coming from the west between Racine and Milwaukee. Skye’s co-owner and navigator, Jane Hoswell, estimates that we will be in the cell within 90 minutes. As the clock ticks down, we organize our headsails, flake and bag the used jibs, and prepare dinner. We flirt with the edges of storms all evening, until a fresh wind line slams the boat at 2 a.m. I spring to the deck to drop the staysail, hoist the No. 3 jib, and pull in the kite.

The storms finally dissipate, and Sunday delivers a gorgeous afternoon of downwind sailing. At 15:09, we are making a steady 9 knots of boatspeed. As I take a break from bow duties to make sandwiches, the annual debate on whether to go over or under the Manitou Islands takes over the cabin. Various crew are huddled around iPads and laptops trying to grab one bar of cell service off the Michigan dunes to update forecasts and routings. The decision is made. We’ll go over. With 21 sail changes thus far, we’re moving along nicely, and I trim the spinnaker as we pass Point Betsie.

After sunset, our luck runs out. We’re becalmed. I scratched the mast to bring wind, a sailing superstition I’ve learned from reading the logs of the 1923 Mac racers. My scratch eventually produces a couple of knots. One hundred years ago, the bowman’s mast scratch supposedly brought “the great hurricane of 1923.” John O’Rourke vividly describes it in his log: “With strong puffs of wind off Sleeping Bear, our lee side was entirely awash, and it was a question of how long we could weather the blow before our canvas or mast should carry away…. Though we had been on starboard tack for over 36 hours, the barometer continued to fall and it seemed certain that the storm center was approaching. We therefore reefed two down as there was no sign of wind or sea diminishing and there was water ahead that was dangerously shallow.”

By Sunday evening, we are navigating these same shallow shoals and reefs that my great-grandfather had fretted about a century ago. The night is pitch-black. Low clouds block the stars and shroud the sliver of moon. Our horizon line vanishes, and we are floating along in the void pointed directly at South Fox Shoals. Alan Cichon, our ace of light-air driving, is at the helm. As each crewmember wakes for their watch and glances at our current position on the chart, they warn him that we are dangerously close to a reef. “We know!” the on-watch crew shouts back. Grant is the third person to pop his head out of the companionway and caution that we are approaching a rock. Luckily for him, raucous laughter from the crew breaks the tension. Cichon and our tactician, Scott Pattullo, keep the boat gliding safely through the darkness.

The morning my great-grandfather finished the 1923 Mac, he wrote in his log: “With the first streak of dawn came the biggest surprise of any Mackinac race. Instead of having two of our class competitors astern, we had two of the big P boats, Intrepid and Mauvoreen, winners of previous Mac Races. Before we crossed the finish line, they both extended congratulations. We crossed the finishing line [Tuesday] at 4:31AM.”

Dawn on our final day also has a surprise in store. Monday at 6:40 a.m., with 29 nautical miles to go, we pass Grays Reef lighthouse and spot Hot Lips, a Farr 40 in our section. It is a competitive boat with an excellent spinnaker trimmer—my sister, Meghan. We owe Hot Lips time, so barring a major error, we know they have us beat, but we decide the fight for line honors between us is worth it. With Marc Bernstein at Skye’s helm, we overtake them, and I hail Meg by screaming the chorus to “South Side Irish,” our family’s musical sigil. But they catch a shore breeze that carries them across the finish line ahead of us.

Soon we can see the Grand Hotel’s gleaming white columns. Our Mac rookie, Nathan Benya, trims the spinnaker as we pass under the Mackinac Bridge. With the finish line in sight, he hands the sheet to Jane Hoswell, who is celebrating her 25th Mac. This milestone is commemorated by her induction into the Island Goats Sailing Society, a coveted honor among Great Lakes sailors. Our helmsman, Robert Libcke, steers us over the finish line at 14:05:38 on Monday, July 24.

In 1923, one observer wrote: “Mackinac Island was a busy place on Tuesday morning, July 24. The boats came in fast and bunched. And the celebrations on shore were numerous and noisy.”

In this regard, a century has changed nothing. On Skye, Benya gets his Mac baptism: a stealthy bucket of water dumped over his unsuspecting head. Jane Hoswell is properly feted for becoming a Goat. Hundreds of temporary “Jane” tattoos are inked on every sailor the Skye crew can find, from the Pink Pony to the Rum Party. And once again, our team is up to the usual island shenanigans.

But not all stories end neatly at the rowdy sailing parties on Mackinac Island. Four months after John O’Rourke won his 1923 Mac Race, he was disqualified on a technicality related to Intruder’s measurement certificate, giving way to Virginia to once again claim the Mackinac Cup. The club’s decision has been hotly debated for a century and become the stuff of Chicago sailing lore. For the rest of his life, he maintained that he was wrongfully stripped of his 1923 victory. While he went on to win many races, he never won another Mac.

My great-grandfather’s story ignited my curiosity and pushed me to the docks of Columbia YC and onto the course that takes us annually to the island at the top of the lake. While John O’Rourke was the fabled sailor who drew me to the sport, I’ve now met many legends forged by the waters of Lake Michigan. On the deck of Skye, I have witnessed grand acts of courage, medical emergencies calmly handled, and countless moments of selfless compassion. That is the great thing about amateur offshore sailing. The sport makes heroes out of ordinary people.