Lightning Worlds

We’ve heard the phrase “learn from your mistakes” a million times, and as my Lightning crew prepared for our 2013 World Championship on Italy’s Lake Trasimeno, that saying rang especially true. We had a lot of experiences from which to draw, and collectively they added up to an elusive world championship title.

At the 2009 Lightning Worlds, for example, we started the series slow but gained momentum as the regatta progressed and suddenly found ourselves in contention to win the championship on the final day. We had our opportunities, but in the end, small tactical errors did us in, and we finished runner-up to champion Matt Fisher. The following year, at the Lightning Winter Championship in St. Petersburg, we were leading the regatta before we capsized on the last leg of the final race and coughed up the title. These were bittersweet experiences because fairly routine strategies and maneuvers were executed poorly and cost us dearly. We knew we needed to learn from these experiences, so that someday when we encountered similar situations, we’d be better able to take advantage of them. How we addressed these shortcomings has come to define us as a team.

In years past, I would have tried to do everything myself, but I’ve learned to delegate. My crew, Ian Jones, is an excellent sailor with a knack for reading the compass and a unique attention to detail. Some call it perfectionism. I call it sweating the small stuff. Ian can prepare a boat as well as anyone, and we enjoyed not even having to think about boat management or maintenance whatsoever.

Likewise, my wife, Jody, is no stranger to competing and winning. She spent years on the U.S. Sailing Team and is a two-time Rolex Yachtswoman of the Year. She is the consummate competitor. She can take complex situations during a race and boil them down to simple strategy and tactics. Her infectious smile and squeaky voice keep us going through the challenging times, while her dogged determination to win ultimately gets us to the top. The differences in our personalities help to balance each other, and it allows me to focus on starting, speed, and last-second decisions.

I’ve also learned to study my toughest competitors. In Chile (2005), conditions were extremely rough and windy, and no one could match Tito Gonzalez’s speed downwind. I sought him out after the regatta to learn about his techniques and discovered that his forward crew hikes extremely hard to leeward downwind, which allows him to sail lower and faster. So we changed our technique: Jody now spends a lot of time hiking to leeward in 12-plus knots of wind. At the Worlds in Vermont in 2009, winds were shifty and difficult to read. Because we were struggling early on, we made a habit of identifying which teams were “in phase” and seemed to have a good handle on the bigger weather patterns. Matt Fisher’s team was one of those teams, so we made sure—to a degree—we sailed in the same areas of the racecourse as he did. Finally, in Brazil (2011), unlike Vermont, winds were very strong and extremely steady (a 5-degree shift was noteworthy) so speed and consistency were essential. Gonzalez’s team is as fast as anyone in breeze, and because of this, he didn’t push the starting line, sailed conservatively, and let his pure speed take him to the podium—that was an important lesson.

“I’d much rather be fast than smart” is another common saying, and one that we fully embrace. On our home waters at the Buffalo Canoe Club on Lake Erie, we worked hard on straight-line speed by lining up with tuning partners, always pushing and defining that fine line between speed through the water and height. There is no substitute for time in the boat, and for once, our speed was the difference maker in Italy.

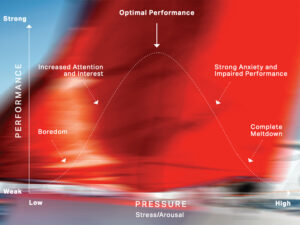

Friends encouraged me to enjoy light-air sailing, which has never been my favorite, and I gained a greater appreciation for things in our control—I focused on the positives, did a better job delegating, and then trusted the team. Because of this, I was relatively calm and collected throughout the championship, never getting too high or too low. But the more important long-term elements of our win were using the lessons of past mistakes, focusing on our weaknesses, and recognizing the unique strengths of each team member.

Organizing the Details

Over the many years of Lightning sailing what we’ve learned is, as the saying goes, “It’s better to be fast than smart.” To this end we focus primarily on boat setup and tuning to ensure we are fast and consistent.

**

1. Rig setup**: I go through my ritual of mast-butt position, forestay length, rig tension, and pre-bend. The Lightning class limit on the uppers is 250 pounds, which is what you want. Using a Loos Gauge on shore, I set the lowers and mast blocks for maximum breeze (half-inch of pre-bend; 250 pounds on the lowers). From there, I make changes for the expected conditions. This gives me an accurate starting point. Jody writes down every adjustment we make to the rig in a WetNotes pad.

2. Boom vang: We sail with less vang tension than most. To put it a different way, most sailors (in all classes) sail with too much vang tension. We’ve found it better to try letting the leech “breathe” a bit more. I learned this from watching videos of Robert Scheidt, of Brazil, sail the Laser and the Star.

3. Mark lines: In particular the backstay, jibsheets, vang, and spinnaker halyard. This allows you to replicate setup and sail trim during maneuvers.

4. Telltales: Good working telltales on all shrouds and the backstay are a must.

5. Checklist: We have a laminated checklist onboard that we reference each day. On it we have references to the boat, our gear, and the weather. It also has specific items for racecourse preparation: wind trends, waves, marks, current, maneuvers, and a debrief. Once we go through the list, we immediately prepare for next race.