ALEX SALDANHA, of Brazil, is a towering presence on Mauricio Santa Cruz’s Bruschetta, and as the team’s longtime tactician, he’s guided the best J/24 team on the planet to countless wins and four world titles, including the team’s most recent at the 96-boat 2012 Quantum Loop Solutions J/24 World Championship in Rochester, N.Y. Sailing an unfamiliar (but heavily refurbished) 32-year-old charter boat was challenging enough, but the big fleet and unpredictable winds made it no walk in the park. We checked in with Saldanha after winning the worlds for some insight into the team’s big-fleet management.

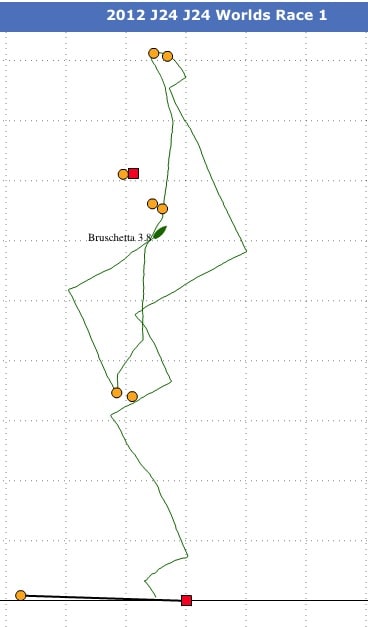

Click here to see the race tracks.

Knowing the fleet size would be larger than normal, and that it would have a lot of amateur teams, what were your goals before the regatta in terms of staying clean and staying away from crowds?

We think it does not matter whether there are 50 or 100 boats. If you get sucked into the pack, then you’re dead, especially in the J/24 fleet. Our first goal was always speed, then clean air, but that didn’t mean that we would not fight for our place on the starting line. It is easy to get rid of the pack going upwind, but downwind was a nightmare. We decided that we would try to never get caught in a big pack at the start and that proved to be a very wise decision.

What venue and racecourse homework did you do?

To be honest with, we did not do much study about Rochester. We sailed there in 2006 at the North Americans and we “knew” what to expect. It turns out that it was completely different than it was at the North Americans.

Before each race, what’s the team’s routine leading up to the first warning signal?

It depends on the wind. We try to sail as much as we can before the first signal to see the high and low numbers on compass. If it’s blowing too much, it’s just a quick check on everything to save energy and equipment. Most important to us is a very good “look” at the course, trying to find the side with best pressure. Sometimes I stay around 5 to 10 minutes just looking at the course and trying to identify pressure as well as holes.

Knowing that the line would be very long (.5 mile), how did you weight the first expected shift with where you would set up on the line. Given the big shifts, was it dangerous to be too far to one end considering the leverage you’d lose if the shift didn’t come?

A very long line (oh boy … it was long) makes things a lot more difficult, but we never tried to be the first on either side: too dangerous. Because it was so shifty it made it possible to play safe and try to climb your way up the beat. Of course, after a pre-race course check, and after deciding which side of the course we thought would be better, we tried to start as close as possible to that side, but always choosing between middle/left or middle/right.

How was your confidence with the shifts and their predictability?

The shifts had a “pattern”, i.e., right 20 degrees, then back, then left another 15 or 20. We knew that the wind would “come back” if it was not looking good. For us, the most difficult thing was the wind holes. Oh boy, that was a nightmare. At one point we were just looking for wind, regardless of the direction. Pressure was good no matter where it came from.

How aggressively did you fight for an end? In some starts you have favored either end, some happily from the middle, but when you were committed to the end, according to the tracks, it was certainly the correct end every time.

As I said before, we never fought hard for one end. It was always “middle-right” or “middle-left.” Having said that, it was all about finding a good spot to start. Sometimes we knew that one end was the place to start, but it was too crowded so the decision was always as close as possible to that end. And again, those decisions where first based on the side we wanted and starting line angle with the wind.

You guys are obviously fast, but how did you manage the fleet versus the shifts?

We had good speed, but not super speed. Finding pressure was more important, especially when sucked up by a pack. Once we found pressure, we immediately got a 10-degrees lift (on either tack).

How did you make the middle work so often when others struggled?

It’s hard for us to bang a corner. It is not in our nature. This is the way we sail. We never want to win by a mile. I guess this is how we did it, and again finding pressure was key.

How do you know when to check back to the middle?

We have a saying from an old sailor friend: “If you can cross, cross.” This explains pretty much everything I guess …

With regard to downwind fleet management, how far out did you carry on starboard jibe before getting back to the middle of the course?

We struggled every single race going downwind. It was so hard because the pressure was always coming from behind. It was more about controlling and staying between the mark and the opponent than anything else.