Raceboats today are obviously much faster than the displacement boats of the past, and as a result, downwind sail trim requires two quite different approaches: You can either tension the vang and run straight downwind, or twist the main and sail an S-shaped course. We’re all familiar with the first option, but the second is actually useful over a much wider range of situations. In a nutshell, the decision you make about which mode to use hinges on two factors: whether the conditions are static or dynamic, and the type of boat you’re sailing.

Static conditions occur when the water is smooth and the velocity is consistent. In these conditions, tension the vang to create a mainsail shape that is uniform from top to bottom. You can do so because aside from perhaps a little wind sheer, the breeze flows consistently over the main from top to bottom. In this condition, you can steer almost straight, with little helm or sheet movement because the wind angle is constant.

Dynamic conditions occur when the wind angle on the sails is rapidly changing. This can happen in a number of different situations, such as when there are larger waves, when the wind is puffy, when there’s enough wind to plane, or in light air.

When there are waves, a wave picks up the stern, the boat accelerates, the apparent wind shifts, and suddenly the sail that was set uniformly from top to bottom is no longer trimmed correctly. The same holds true when the wind becomes puffy. With each puff, the boat accelerates, the apparent wind rapidly shifts forward, and the sail will not be set correctly for the new wind, or the next puff will come from a different direction.

When planing, the helmsman is usually steering so much that the mainsail trimmer will be unable to keep up with the boat’s course changes. At the other end of the spectrum, in light air, shifts and puffs are generally big, so they can dramatically affect the wind angle. Regardless of which dynamic conditions you’re sailing in, the result is the same: Sometimes the sail will be perfect, and other times, none of it will be set correctly.

In each of these three situations, you’ll recognize that there is a problem with mainsail trim when you notice the boat slows and becomes difficult to steer. Ease the vang and outhaul to induce twist and ensure that at least part of the mainsail is always trimmed correctly all the time. Don’t just ease the sheet; that won’t give you any power.

In these conditions, a good rule of thumb for apparent-wind sailing boats is to put the boom over the leeward corner. You can adjust the twist from there. Essentially, you’re trying to put more shape in the main and add twist, just as you do when you’re sailing upwind in waves. You’ll know you have it right when the boat becomes more forgiving to steer. That’s because part of the sail is always trimmed correctly at any given time.

Twist is especially useful when planing. Because it makes the helm more forgiving, you are free to steer whatever course you need to maintain the plane. Knowing where your particular boat’s crossover is between a dead downwind course and a planing course will determine when you should start twisting the sail. On most boats, the polars show that as it gets windier, you should sail deeper and deeper, at optimal VMG.

At some point, however, the polars will also show that you need to put the bow back up for better VMG. That windspeed occurs when the boat starts to plane. A Farr 40 might be sailing deep — at maybe 160 degrees — in 20 to 22 knots of breeze with the pole squared back. Then the wind picks up to 23 knots and more.

You should put the pole on the headstay and start sailing at 145 degrees. The boat’s planing and the jump in speed will pay off at the leeward mark. The polars for that type of boat have a large hump, and it takes a lot of wind to transition from VMG sailing to planing.

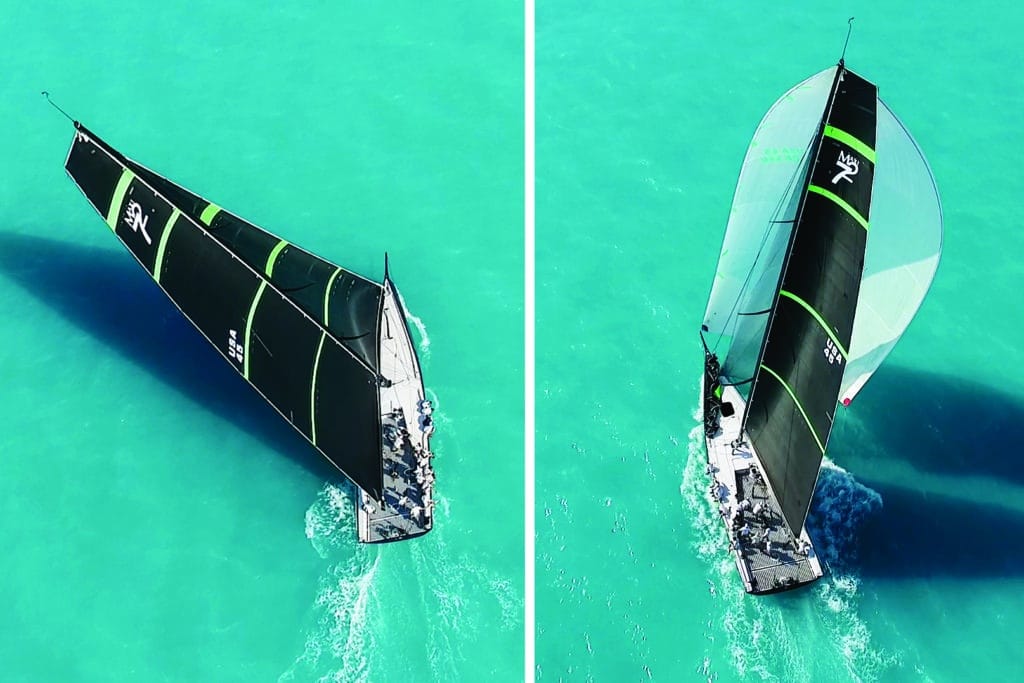

On the other hand, polars for newer high-performance boats have very flat transitions, meaning they go almost effortlessly from the VMG mode to planing. For instance, a Melges 32 has a very flat curve, with no big hump: It’s only blowing 14 knots, and all of a sudden you’re planing, so the transition is less obvious. Wherever the transition happens for your boat, typically you will start steering more, and that’s when you need to get the boom in and induce twist.

The bigger the waves, puffs and shifts become, the more your wind angle is changing, becoming more dynamic, and the farther in the boom comes. At some point, it will be almost on centerline, which seems counterintuitive, considering you’re sailing downwind. To carry the boom in that far, you need very little vang. The least amount of vang would occur in 20 knots, big puffs and huge waves, and in those conditions, the boom could be on centerline. If the mainsheet trimmer can pump, he should be pumping the main leech by pulling the mainsheet to exert downward tension, as for a vang. In this mode, the boom will go from the leeward corner of the boat to almost on centerline. The last bit that you pull on pumps the leech tight, as it would if you were trimming the vang. It’s different from the traditional pump you would do on an FJ or 420, where the boom vang is on and you pull the sail without a lot of twist, trying to capture all the breeze. Instead, in the above scenario, the boom is actually quite light because there’s no load in the top half of the sail.

Figuring out whether you should be set up for static or dynamic conditions is the first place to start when working on your downwind speed. The next step is learning how much twist is perfect for your boat. Get this correct, and you’ll get to the leeward mark much faster.