It has been blowing 30 to 40-plus knots all night, and we can finally see the sea state at first light. It was a wild night bombing down massive waves in the pitch-black under a full main and a heavy-air running spinnaker. Without instruments, our only guides were a flashlight taped to the backstay, so we could barely make out a masthead fly and the dim glow of the running lights. I vividly remember passing waves at such a velocity that we flew off the front of one wave and slammed violently into the back the next. This happened two or three times in succession.

An hour before the sunrise, the boom broke. We thought that the competitive part of the race was over for us, so we took the opportunity to rest and hobble down the racecourse. But we were still in contact with the leaders, so we decided to try inserting the reaching strut into the boom and “grinding” the boom back together. One rusty hacksaw blade and—voilà!—a short time later, we were back in the race with a reefed main.

This was Robert Plant’s (no, not that one) Hobie 33, then named Ballistic, and the year was 2001. Unfortunately, along with the sunrise came the realization that we could see daylight through the hull-to-deck joint most of the way around the boat, and after finishing the race, we thought that was the end of the Hobie 33.

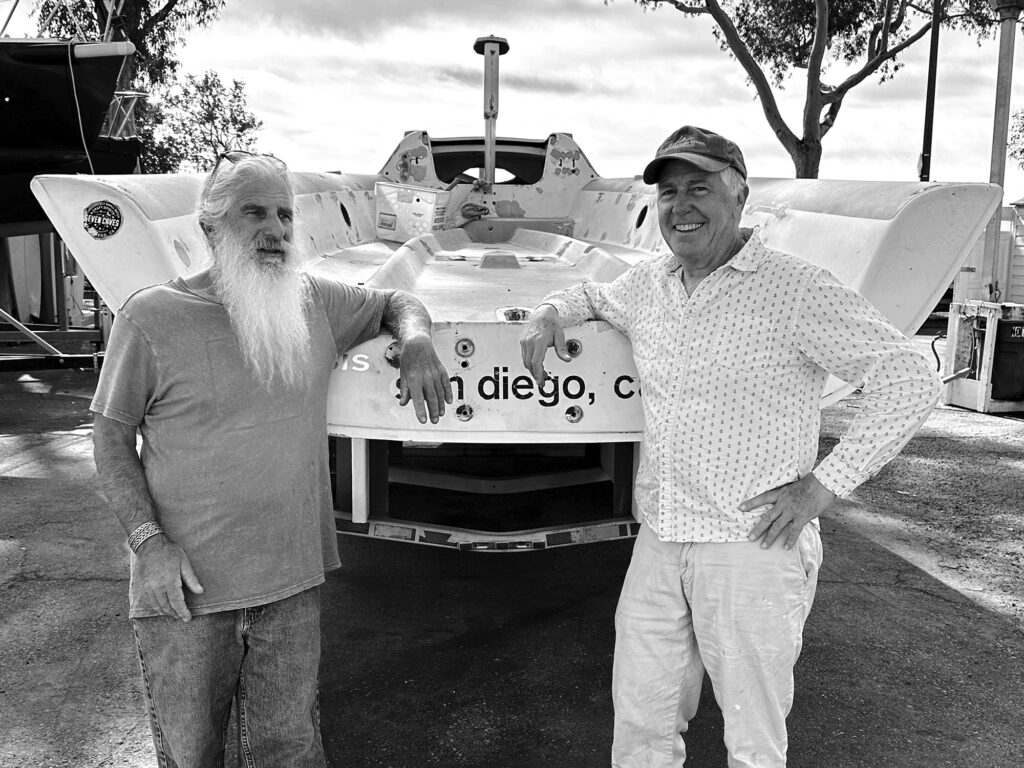

Instead, Plant and my father, Jon Shampain, decided to rebuild the boat, stiffen it back to its previous glory, and add an open transom.

Plant, a longtime sailor and architect by trade, is well-versed in construction techniques and design. My father is a long-time boat captain, navigator, and delivery captain around Southern California who is well-versed in what makes a good sailboat. Between the two of them, and with my prowess for deck layouts and rigging systems, we were sure that we would have a great platform.

My father became a boat partner with Plant, and Still Crazy was born. Years later, another full retrofit was done, and I became a third partner.

By 2019, however, we were feeling like we had “been there, done that” with Still Crazy. We all were busy and didn’t have much time to sail it, so we let it go to another owner, who now races it shorthanded on the Great Lakes. By early 2023, Plant and my father got that itch again and started a dialog. “Maybe we should get a boat again.” These guys sure do like a project.

They preferred the 30-foot sportboat range but wanted a boat that was a bit easier to get around and easier to sail. They ended up with specific criteria: an inboard engine, non-overlapping jibs, no runners, fixed keel, and economical. And, of course, it had to be fast and fun to sail.

We considered a Farr30, a Flying Tiger, Melges 32, Columbia Sport 30, Henderson 30, and other similar boats. But when a local Melges 30 with an outboard engine came to them for a song, they couldn’t say no. I couldn’t even attempt to talk them out of it. It was a proven boat with a good track record but hadn’t been sailed in nearly 10 years. And it showed. They got their project boat, and it needed everything except for some seemingly decent unused sails that came in a questionably soggy box.

First built in 1995, the Melges 30 started out as a supersize Melges 24. Piggybacking on America’s Cup technology at the time, the design was jazzed up and pushed to another level. The first boat actually had a trim tab on the keel, which was pretty cool and really fast but cost-prohibitive, Harry Melges III says. Later, they learned that the boat was too fast for the articulating bowsprit in most conditions. Eventually simplicity won out, and the Melges 32 One Design was born using the same molds. All in all, it was a short production run, with only 16 of them ever built.

While Plant and my father started stripping hardware, they found moisture and elongated holes just about everywhere in the deck and bulkheads. The decision was made to remove every piece of hardware, every fastener, and fill every single hole inside and out. Delaminating gelcoat also needed repair, then everything faired and prepped for paint.

Time was also taken to attempt to stiffen the boat close to its original build. Knees, which are basically mini bulkheads between the deck and the hull, were put under the stanchions. These are a great addition to older boats because, as a boat ages and gets softer, the deck starts flexing. Years of pushing and pulling loads have been applied to the tops of the stanchions, causing the deck to soften. Mast steps of these older boats can get soft and can sag into the boat. This can make it harder to keep proper rig and headstay tension, so to combat that, we applied carbon cloth around the mast step area to prevent any future sagging. Other questionable areas received extra layers of cloth as well.

It was also important to Plant and my father to be on the drier side when sailing, especially down below. And neither has much interest in nonstop bailing in windy conditions. The Melges 30 was designed with runners on a purchase system that lead below deck through openings in the cockpit floor. We structurally sealed these and will add an above-deck system with winches. It will add a little weight, but the added safety and peace of mind using winches to hold high loads, combined with less water intrusion into the interior, will be a net gain. The original design had the mainsheet fine-tune down below as well. We’ll move that above deck like the Melges 32 and seal up an additional hole. My father intends to lead the articulating pole control into the companionway, which will remove two or three more holes in the cockpit.

After countless hours of prepping, fixing, replacing, adding, and deleting structure and parts, the decision was made to take it to a local boatbuilder/boat painter to have the topsides and nonskid sprayed, along with an epoxy bottom. It was a hard decision because Plant and my father had a budget and wanted to do it on their own. But with hours of fairing required and a desire for a professional, finished look, they succumbed to outside assistance.

While the boat was away at the “spa,” they took the trailer to be refurbished and raised the bunks a few feet. This will allow the rudder to be left in the boat while dry-sailing locally, and will also add space for storage boxes on the trailer. Simultaneously, the stern pulpits were modified by Steve Harrison at Harrison Marine in San Diego. Legs added to the stern pulpits would prevent movement when hiking and pulling on them.

Once the boat was back in their hands, Dad and Plant finished the painting of the interior, and then the mast and boom and associated parts such as instrument brackets, tillers, hatch boards, etc. At this point, we had a completely blank canvas, allowing me to design an entirely new deck layout with the help of Harken.

Having eliminated all the below-deck systems, we’ll be going to winches for the runners. The mainsheet fine-tune will become external. The jib lead will become a floating lead system, with inhaulers for the jib and genoa staysail. Finally, because the boat will someday have a square top, we’ll get rid of the backstay and add top-mast backstays to the runners. They will be on new Harken winches so that handling will become easier. All this will be done with the help of a running-rigging package from Marlow Ropes and an instrument package from B&G and Navico.

In future articles, we will dive into what parts we chose and why, and what worked and what didn’t. Everything we do will be budget-minded but we’ll be sure to have the correct gear so that we can race successfully, all the while inspiring others to keep aging race boats modern and competitive.