Dynamic Dialogue

On top boats, the dialogue while racing will typically involve four key people: the tactician, helmsman, mainsail trimmer, and jib trimmer. Granted, not everyone has the luxury of sailing with a great helmsman, trimmer, and tactician, and on a lot of boats, crewmembers have multiple roles. The helmsman, for instance, might also trim the main, or the jib trimmer might call tactics. But for our purposes, we’ll split up the roles, with each person focusing on a single aspect of getting the boat around the course as quickly as possible. Now, let’s go through a maneuver. Imagine yourself on an upwind leg, on port tack, encountering a starboard tacker. Here’s what you might hear as the boat prepares for and then dips the starboard-tack boat.

Mainsheet trimmer: Boat 17 is coming in on starboard tack, and we’re not crossing.

Tactician: Got it. I see him. We want to continue on port tack; we’re going to dip ‘em.

Mainsheet trimmer: Copy.

Mainsheet trimmer [to helmsman]: See boat 17? We’re going to dip him in three boatlengths. It’s a medium-sized dip.

Helmsman: Got it.

Mainsheet trimmer [to jib trimmer]: Medium dip, no ease on jib.

Jib trimmer: Got it.

Mainsheet trimmer [to helmsman]: Keep going . . . Keep going . . . Bow down, now . . . A little deeper than that . . . OK, start coming up.

Helmsman: We’re over target speed but not on our angle. I need more helm.

Mainsheet trimmer: I’ll sheet in a little to bleed off some speed.

Helmsman: OK, we’re now at target speed. The helm feels good.

Tactician: That was one of the best dips we’ve done. Try a little more mainsheet eased going into the dip next time. It felt like we came close to stalling.

This scenario illustrates a number of key ingredients. Let’s break down what happened.

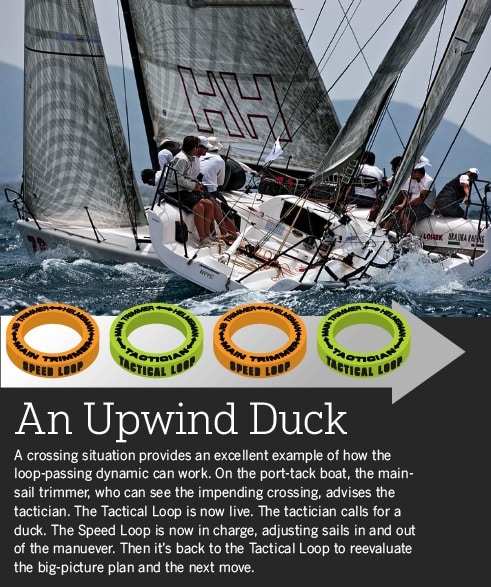

The conversation operates in two “loops.” The first is the tactical loop. A starboard-tack boat is approaching, and the tactician makes the call to dip because the big-picture tactics demand that they continue on port tack. Once that tactical call has been made, the tactician turns it over to the speed loop. That includes the mainsheet trimmer, the helmsman, and, at times, the jib trimmer. They will guide the boat as quickly as possible through the maneuver and back on course. Once the maneuver is complete, the tactician briefly jumps in to provide feedback. From there, the boat will be in the speed loop mode until another tactical situation arises.

Tactical loop

The above situation is a pretty standard maneuver—one that has been well practiced. All the tactician has to do is make the call—”We’re going to dip ’em”—and the responsibility is then handed over to the speed loop. As a tactician, I will occasionally chime in to the speed loop, but I don’t want to be relied on for that. Ideally, I try to focus 95 percent of my time just on boat placement.

When does the tactician get involved in the speed loop?

Imagine you’re on the starting line, you’re to leeward of another boat, and you’re bow back, meaning you’re on the edge of getting rolled. The boat to windward is reaching off slightly. There’s a lot of room to leeward of you, and your success at that one moment is really the race—you have to maintain position. Now, everyone has to concentrate on boatspeed. In this situation I’ll help out by managing our position by saying something like, “We’ve got to go faster, bow down!” If it’s going to take a while to work out from under the other boat, I might say, “The race is to windward—plenty of room to leeward. This is your target for the next three minutes.” And once our speed is up, I’ll confirm, “That’s good—holding speed now.”

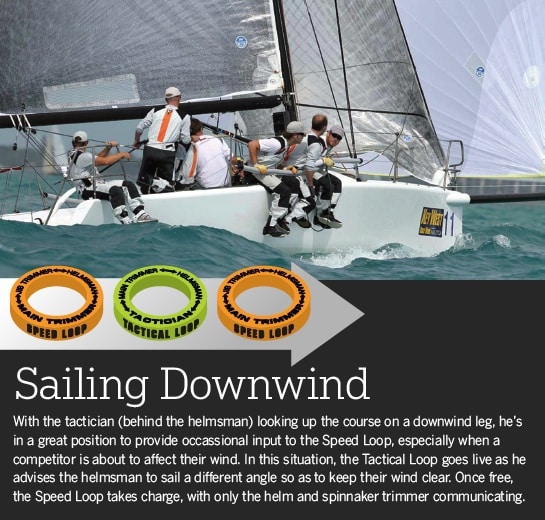

Another time I’ll jump into the speed loop is when we’re sailing downwind, and a competitor jibes on our air. To stay in clean air, we may need to sail off from the best VMG angle. This will result in having more or less pressure on the trimmer’s sheet than they normally sail with downwind. Consequently, they can’t rely on sheet pressure to guide the helmsman in finding the correct downwind angle. The correct angle can only be found by looking at the other boat, which is not ideal for a helmsman or trimmer. The tactician is the only one free to judge their speed, position, and tactical situation.

When one of these situations ends, when the windward boat tacks away, for example, I’ll say to the main trimmer, “You’ve got it.” In other words, I’m checking out of the speed loop, it’s back to you guys. This way, we all focus all of our energy on speed when the entire race depends on it, and when it doesn’t, we can seamlessly move back into the tactic and speed loops seamlessly.

Speed loop

In our earlier conversation, the main trimmer is driving the speed loop conversation, calling the degree of dip to which the helmsman will steer, making sure the jib trimmer is onboard with what’s happening, and responding to the call for more helm. This takes the weight off the skipper—lets him concentrate on driving. Typically, the helmsman and mainsheet trimmer are sitting next to each other, so communication between the two is quite easy. And typically, the mainsheet trimmer says what he’s trying, and the helmsman gives him feedback on that. I think of it like sitting through an eye exam. The optometrist keeps putting different lenses in front of you, asking, “Which is better—this one or that one?” It’s the same type of conversation between the main trimmer and the helmsman. And, like at an eye exam, one person has to drive that conversation. The helmsman, jib trimmer, or tactician should help and make suggestions, but the decision is up to the mainsheet trimmer. It’s OK if the helmsman wants to drive the speed loop, but this means he or she will not be focusing on driving. The thing about the mainsheet trimmer is that he’s looking at the main the whole time, which is not easy for the helmsman to do. The trimmer is only missing one piece of feedback—the feel of the helm.

The other part of the speed loop involves the main and jib trimmer. In the above situation, the main trimmer is driving the conversation. What’s a typical conversation between the mainsheet trimmer and the jib sheet trimmer sound like? Since the main trimmer can’t really see much of the jib, he will often look at it in terms of its affect on the mainsail. If the jib isn’t trimmed hard enough, the main trimmer might say, “I can’t see you in my sail,” meaning there’s no backwind in the mainsail. If it’s a puffy day, and the main trimmer needs to open the slot for a big puff, that’s the main trimmer’s call. Someone will be calling pressure, saying “It’s only here for 15 seconds,” and the mainsheet trimmer might respond with, “I’m going to luff for 10 of it, but then we’ll be fine.” That tells the jib trimmer the jib does not need to be eased. There are many times when the jib trimmer may want to change the lead position, sheet tension or something else. He usually goes ahead and does that, then asks the main trimmer for feedback. That last part—feedback—is critical in keeping the boat fast.

Taking responsibility

It’s important to know who is responsible as you move from the tactical loop to the speed loop and back again. You can’t have a bunch of leaders in every situation. And you need to be able to hand that responsibility off in different situations. I think of this as similar to passing a ball back and forth in basketball. The guy with the ball has the responsibility; he can determine how long to hang on to the ball and whether or not to take a shot or pass it to another player. In the same way, in the opening conversation, the tactician has the “ball” and calls the shot—ducking the starboard tacker and continuing on port tack. He then passes the ball off to the mainsheet trimmer, who is in charge of the speed loop. The trimmer calls the mechanics of the maneuver, in this case, a “medium dip,” guides the boat through the maneuver and back onto course. Once on course, the speed loop is full on, with the helmsman and mainsail trimmer communicating about speed and pointing.

A good part of this hinges on the talent onboard and using it as best you can. I often sail with Jeff Madrigali, who is the main trimmer and, among other things, really good at looking at waves and picking the best places to tack. If we need to tack, I’ll make that tactical call by saying, “Stand by.” That passes the ball to Madro. The jib trimmer then shifts off the rail, and gets ready to tack. Madro now has about 10 seconds to find the best place to tack the boat. Similarly, if we’re coming up to a boat we need to leebow, I’ll simply say, “Leebow boat X.” That hands the ball to the speed loop. Madro will then respond with “Got it” and take us through that maneuver.

The handing off of responsibilities is planned out before we even leave the dock. It has to do with his strength in handling those situations and also keeping me out of it. I always tell teams that the more they can deal with boat handling, the boat-on-boat situations, calling the spinnaker sets and takedowns, etc., the better I can deal with managing the fleet and watching the wind.

Make it straight talk

Robert Hopkins, our coach on Luna Rosa, introduced me to the importance of word choices used onboard. We had a lot of different nationalities, personalities, and so on. If someone said something to you, you had to acknowledge with “copy,” like the military does. For me, even if everyone’s speaking the same language, it’s really important to hear an acknowledgement, to make sure they heard and understood.

People always have a specific response, whether it’s “Got it!” “Copy,” or something else. Then, there’s no question about whether or not a message got through. It doesn’t make much difference what you say, as long as it’s concise and loud enough. Without the verbal acknowledgement, then, as tactician, I end up asking, “Did you hear?” and eventually verbally driving the boat through the maneuver. When this happens, the whole team ends up sailing with our heads in the boat, doing something that should be rather straightforward, such as a dip, and not paying attention to the big picture.

I usually don’t present alternatives, such as, “If he tacks on us, we’re going to tack.” That gets too complicated. I try to state the goal, so we’re all working toward it, and as the situation changes, I make adjustments. In the opening scenario, the tactician clearly states the goal right at the beginning: “We want to continue on port tack.”

I also try not to tell people too much too far ahead of time. If I say, “In five boatlengths a boat is going to cross well ahead” or something like that, team members start moving out of position to look, and before you know it, the boat’s out of balance and going slower.

One of the occasions when I do paint a picture for the crew occurs at the windward mark. Suppose we’re coming into the windward mark on port, we’re the windward boat, and there’s a boat to leeward of us on the same tack. That boat is just far enough away from us that we can’t pin it, or prevent it from tacking until we do. It’s clear that boat will tack on the layline. Then, I might say “There’s a boat ten boatlengths to leeward, and they’re going to tack. When they do, we’ll tack and leebow them.” Now, when the other boat tacks, our helmsman and mainsheet trimmer know the situation ahead of time. We’ve briefly gone into the tactical loop, and then the ball is handed right back to the speed loop, who will guide the boat through the leebow.

I’m also careful to always say the most important thing first. On the Melges 32 I sail on, you might hear me say to our helmsman, “Kip, keep driving fast, I’m going to paint the picture for you,” and explain the situation. Or, “Keep driving; I’m going to yell to another boat.” In each of those examples, the emphasis is on making sure the helmsman continues doing what’s most important—steering the boat. Then, with that as his primary focus, I can describe the next move. The dynamics between the tactical loop and speed loop certainly vary from boat to boat. A lot of that hinges on the capabilities of the individuals involved. But even if you’re not functioning at a world-class level, making sure the roles are clear, the priorities are set, and the means of communication are in place will boost the performance of any team.