Some years ago, I was racing at Key West Race Week aboard a Farr 40. All the boats in the fleet go about the same speed upwind, so the outcome hinged on what I call “geographical positioning”—where you were on the course relative to the competition. Yes, you had to have a good start, and you had to be in the right spots for the shifts and puffs, but you also had to pay a lot of attention to your position relative to the boats around you. If you had to duck a boat or you got tacked on, all of a sudden things started to snowball, and a top-10 position could quickly drop into the 30s. This was most apparent as boats started converging on the windward mark. Seeing that happen, I started playing the inside of the lead pack, something I call “leading the leaders.” In a fleet with anything more than 10 to 15 boats, apart from starts, it’s the biggest single passing lane.

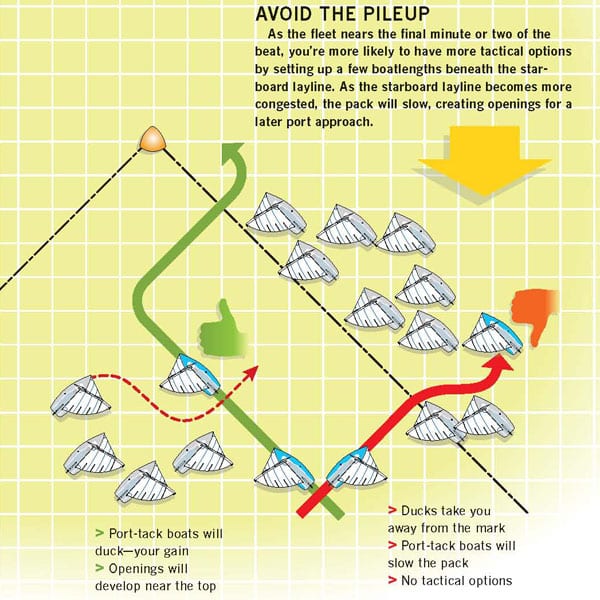

Because packs develop on both laylines, boats coming in on the weather mark laylines, especially the starboard-tack layline, will slow each other down. Once on the layline, you have no option but to follow the pack into the mark. The longer you’re there, the worse off you’ll be.

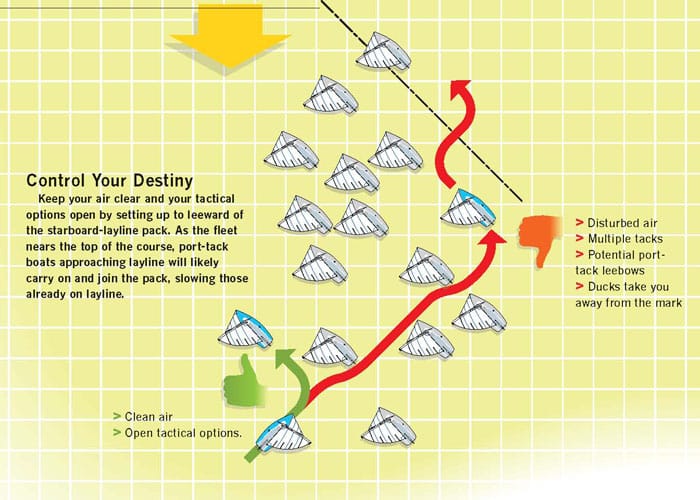

To lead the leaders, position yourself toward the center of the course, relative to that pack. You may be behind most of them, but you’re eliminating one of the key variables over which you have no control: what other boats are going to do, such as tacking on you, forcing you to duck, or leebowing you, all of which might force you to the layline early. This keeps your air clear and preserves your tactical options.

If you’re on starboard tack in the correct zone below the layline, boats coming in on port won’t bother to tack on or in front of you because they don’t want to do two extra tacks. They’ll usually go straight to the starboard layline. Think about the following situation: Your competitor is on port tack, about 10 boatlengths from the weather mark, headed toward the starboard layline. He sees you approaching on starboard tack. His choices are to leebow you or dip you.

A lot of times, the conservative thing for him to do is just dip you and get to the layline. But once he dips, he’s now behind you. So, if you’re the starboard-tack boat, and you can find that perfect lane where port-tack boats will more likely dip you than lee-bow you, they’ll end up sailing down the ladder. The result? You gain.

The further I am from the mark, or the further I am back in the fleet, the further from the layline I’ll tack to starboard. For example: If I’m on port, 2 minutes from the starboard layline with 10 minutes on starboard, and there are just a few boats ahead of me, I’ll tack onto starboard. If you’re not leading, you have to expect that, in the next 10 minutes, someone will leebow you or someone will tack on you. In a big fleet, that might happen a couple of times. The last thing you want to do is to be forced out early to the starboard layline. So leave yourself enough room to take a couple of steps to the right, if you need to, as you near the mark.

When do you make your move toward the layline? Apart from positioning of other boats, you need to consider current, windspeed, and waves. If there’s current running with the wind, get to the layline earlier, because the current tends to cause boats to stack up on the layline, leaving few openings for late-arriving port tackers. If the current is going in the opposite direction to the wind, it will tend to open up spots on the layline, and you can wait to set up on the starboard-tack layline. In light air, you can get on the layline later, because all the boats in line there will affect each other much more, creating a lot of gaps. But if you’re in perfect conditions—flat water, 12 knots or so of breeze, and no current—you need to get on the layline pretty early. Everyone will go the same speed, and the wind shadows and waves don’t affect the boats that much. There won’t be a lot of spaces into which to tack.

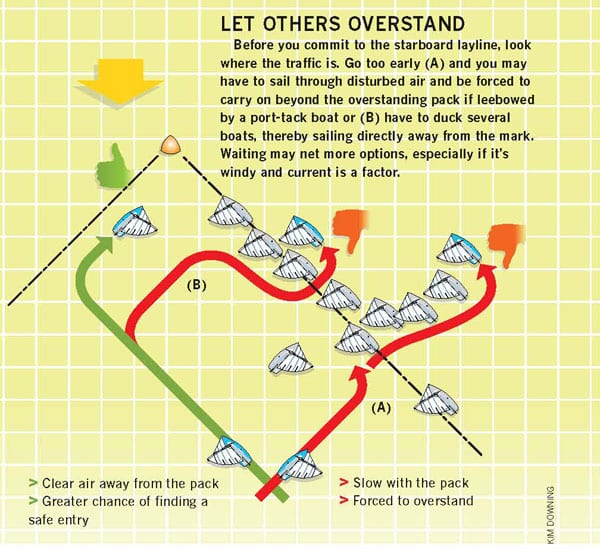

Also consider the degree to which boats are overstanding the mark. I call it the “shape of the pack.” If it’s a pack with a lot of boats tacking on each other, there will be openings. If you see a group of four or five boats, bow even, on port, going to the starboard tack layline, they’re going to tack at the same time and form a perfect lineup on starboard, making it tough to find an opening.

And finally, even if you’re in the perfect lane below the starboard layline, you must watch what’s coming from the left-hand side. If there’s just one or two boats coming, and they’re ahead of you, it’s not a big deal. If there are a few boats behind you, that’s not an issue either. The boats to keep an eye on are the ones making big dips or crossing just behind you. Those guys are going to make the starboard layline more crowded right where you will be looking for a hole into which to tack. If you’re within 30 seconds or so of the starboard-tack layline, you’ll want to either slam dunk or leebow them. If there’s a big hole on the starboard-tack layline, then a slam dunk is best. If there’s not a good hole, or you’re not sure, then you should lee-bow to keep your options open.

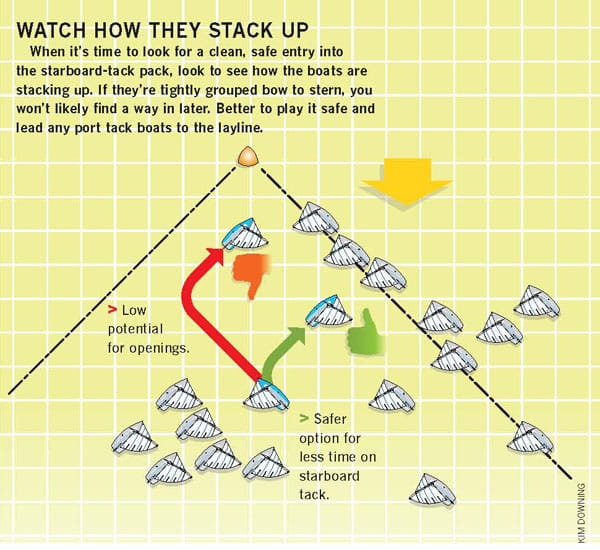

What happens if you’re coming in on port and the hole is so small you cannot complete a tack in it without fouling a starboard tacker? The best solution is to cross the starboard boat and then tack above them. Make sure you communicate this to the other boat, though. I’ll say, “I’m going to cross and then tack.” This prevents them from luffing up as you cross, thinking that you’re going too close.

Another problem can occur when the hole you were hoping to get into is either further down the starboard line than you anticipated or has disappeared altogether. The best solution is to just slow the boat by luffing, stay on port tack, closehauled, and wait for a hole to appear. If you duck the line of boats, you’re going back down ladder rungs, sailing in the opposite direction of all the starboard tackers. Then, when you do find an opening in the starboard-tack lineup, you have to make a sharp 180- degree turn, which kills all your speed and makes your loss even greater.

In this situation I’ll often wait there and let other boats clear out. Who knows? Maybe someone else will crash in and open a hole or punch high and make a gap. Regardless, you need to be ready to accelerate. The worst case is that you wait until the hole that you would have ducked and tacked into comes along. When the opening finally comes along, be ready to bear away and build up a little speed before tacking into the hole. This scenario played out for us in a recent Melges 32 championship. We sat head to wind for 10 to 15 seconds at the weather mark, waiting for starboard tackers to go by, while a boat that was initially five feet or so to leeward of us headed off and dipped everybody. A hole opened up, and we went around the weather mark around sixth or seventh. The other boat rounded in 25th.