When you see pictures of top pro teams hiking upwind, shoulder to shoulder, head to toes, know that they’re not doing it for the photographer. It’s fast. Setting up where your crew is positioned might seem straightforward, but if you look more closely at the differences in how your boat reacts by moving crew around and experimenting, you might find there’s a better setup for your crew weight placement to get maximum speed upwind. Here are a few tips I’ve used over the years to get the team’s weight oriented correctly.

Use the widest part of the boat. It seems pretty basic, and maximum beam won’t necessarily be the exact spot to place crew, but situating the crew at the boat’s widest part will get their weight outboard the farthest, providing the best hiking leverage. When I jump into a boat for the first time, I place the biggest person on the team in that max-beam spot and fill in around him, taking into consideration other crew dynamics.

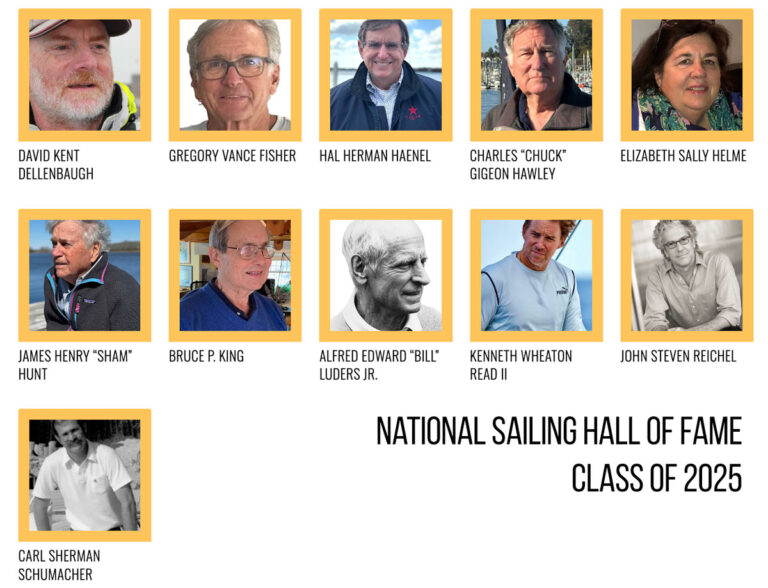

Check your flow off the transom. I picked this one up at a Greg Fisher symposium many years ago. He turned me on to watching the water flow off the back of the boat to make sure it was smooth and even. Next time you’re in your boat, slide abnormally aft and observe the flow off the transom. You can also listen to how it gurgles, which is a good audible clue you can use later. Then move forward. The flow should clean up immensely. The point at which your flow changes from disturbed to smooth should be the target spot to put your fore-and-aft crew weight. On some dinghies, you might try clear transom flaps so you can see the flow better.

Watch your knuckle. On many boats, the lower part of the bow, also known as the knuckle, indicates how the crew weight should be oriented fore and aft. When sailing in waves, the knuckle should be out of the water 50 percent of the time. In lighter winds, it should be in the water 90 percent of the time. In bigger breeze, it should be out of the water 90 percent of the time. If your boat has a fine-entry bow, have the forwardmost crew monitor how the knuckle meets the water and adjust crew positioning accordingly; you’d be surprised how shifting one crewmember a few inches either way can make a big difference.

Dampen the pitch. Pitching is a big-time speed deterrent. Placing your crew weight together ensures you’re doing what you can to limit pitching when going through waves. Get your team together, tell them not to be shy, and pack as closely together as possible. I’m always surprised to see how far apart many teams sit on the rail. In the Midwest, we often sail on smaller lakes or enclosed bays, and like clockwork, the motorboaters hit the water about the time we finish our first lap, creating a lot of chop. If you can get through it cleanly, it’s a great opportunity to gain. The key is to reduce pitching. You can do so by centering your crew weight in the middle of the boat, usually shifting in off the rail, and moving everyone close together. My regular crew, Jeff Eiber, and I have even tried standing as we enter a set of waves, balancing the boat with our legs, and that seems to work well. You can’t eliminate the effects of chop, but you can reduce the pain it creates.

Communicate with your team about how the boat is balanced. We’ve all sailed in inconsistent winds, where you’re hiking one moment and sitting inboard the next. As the wind makes these transitions, the best teams keep their movements as smooth as possible. The best thing you can teach your team is the importance of a consistent angle of heel. Keep in mind that it’s sometimes difficult to teach “feel,” so clear communication will help any teammate develop a better sense of when the boat is balanced and going fast.