So many factors go into prepping for a typical around-the-buoys day race: rig tune, sail selection, start line bias, course skew, and currents, but one of my biggest pieces of advice to sailors is to remember to regularly “look up!” One overlooked component of sailing strategy is how the wind behaves around the clouds and by understanding how they can influence wind patterns at the surface, you can gain a competitive edge on the water, especially if you are the only one looking around at the clouds. Clouds are a big topic, of which entire books have been published, but to get you started, here are my five top tips for cloud management.

Incorporate clouds into your race strategy

What information can clouds really tell us about what the wind will do in the next hour, next half hour, or even the next 5 minutes? A lot, actually. First, we need to know which clouds we should pay attention to, and which ones we can ignore. This comes down to height, size and shape. Clouds that are low to the surface, have a flat or dark bottom, and/or are puffy in nature are the ones we want to pay attention to. If you see clouds that are changing quickly, getting taller (taller than they are wide) or moving fast, those will also tell you a lot about what the wind is going to do. For example, cumulus (those puffy, cotton-ball-like clouds) over land that are growing taller indicate heating and a strong thermal component to the wind that day, which is likely to be a sea breeze in action. Fast-moving clouds tell you what the winds are doing at the upper levels of the atmosphere. Thin, wispy, or high-level clouds could offer insight as to what the weather will do in the next 12 to 24 hours, but these clouds will not directly impact the wind on your short windward-leeward course.

On days where clouds are a significant feature of the racecourse, I’ve made checking the clouds part of my pre-race routine. For example, in Miami, where cumulus clouds are routinely moving across the course, I make it part of my routine to look up and check the speed, distance, and height of the clouds every 5 to 10 minutes. Set an alarm on your watch to remind you, just the same way you would systematically check the wind angles and bias on the start line.

I also check to see how much cloud cover there is across the course, and whether the coverage will change at any point. For example, if the left side of the course has about 40-percent cloud cover (puffy cumulus) and the right side has 20, I will favor the right side of the course (all else being equal) because there is more blue sky in that direction and therefore more of the upper-level winds reaching the surface without being impeded by clouds.

Avoid sailing underneath clouds

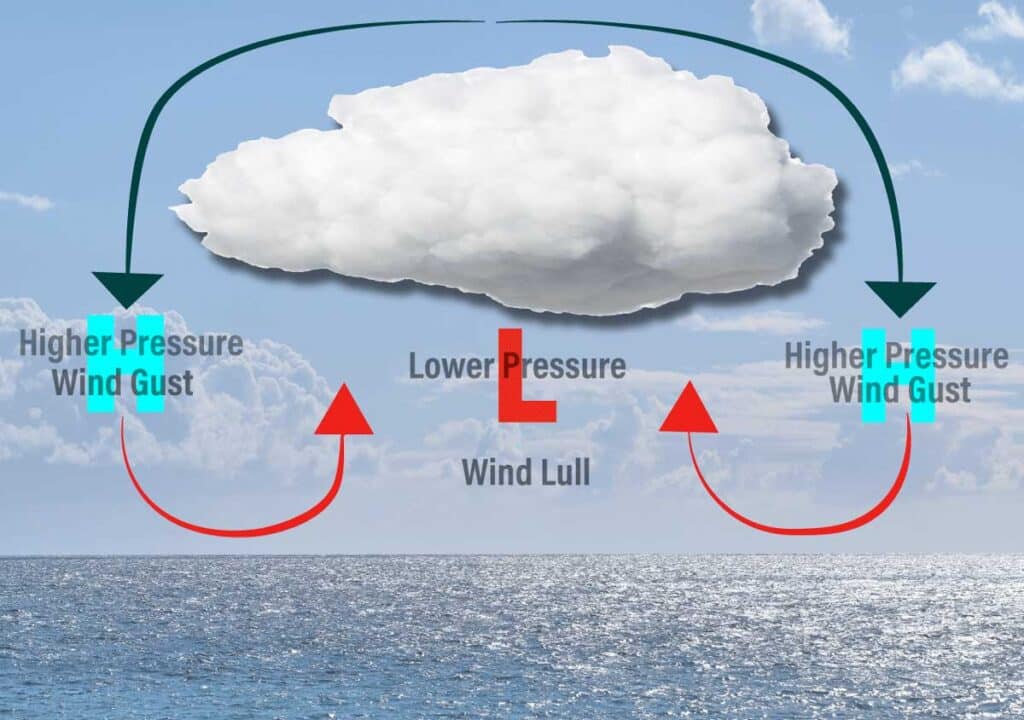

Cumulus clouds are a clear indication of thermal updrafts, which are pockets of warm air rising from the surface. As warm air ascends, it creates lower pressure underneath the cloud, and much less wind at the surface (a relative wind lull). This phenomenon also generates more wind around the cloud’s edges where the air is sinking (relative high pressure) and can provide a puff if you stay on the edge of the cloud—just don’t get stuck underneath it. The best way to get good at reading the clouds, and learning where the edges are, is to practice. It takes experience with many different types of clouds to get really good at nailing the pressure zones and judging the speed at which they are moving

Check for rain

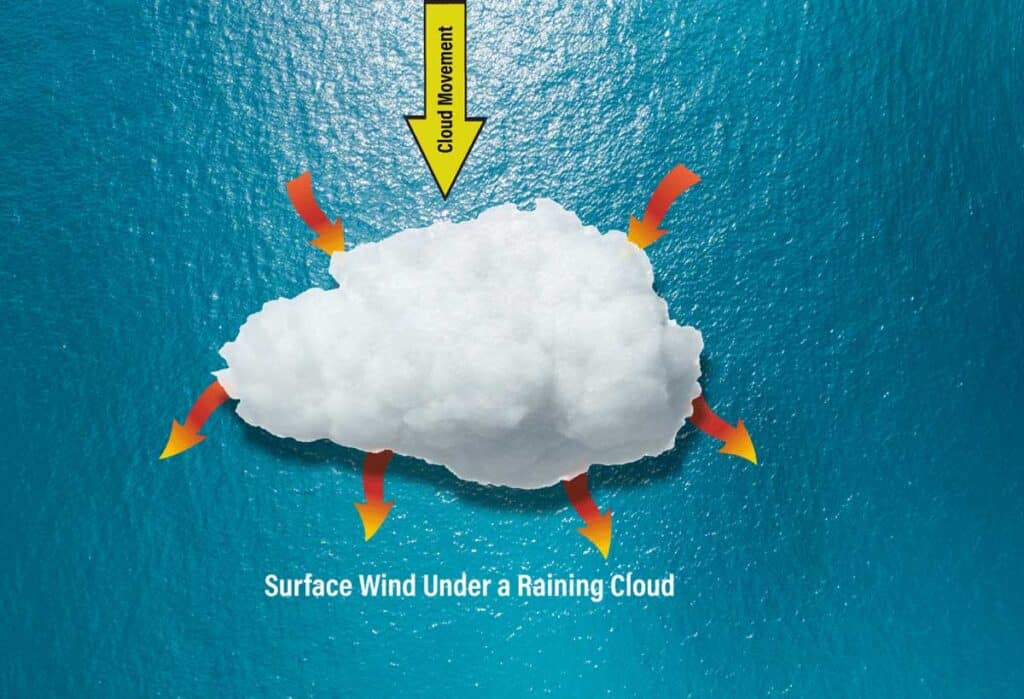

It’s also important to note whether the cloud is actively raining or not, as this will change your strategy dramatically. Clouds that are not raining are as described above, with rising air underneath. Clouds that are raining, however, also have a downdraft near the rain. The strength of the downdraft will depend on how big and intense the rain cloud is. Smaller isolated rain clouds will have a quick downdraft that will flow out from the leading edge of the cloud and provide a small gust of wind as the rain starts initially falling (you usually feel this gust first on the leading edge, or as it is coming toward you.) If you are on the side of the cloud (it is passing to the left or right of you), the wind will tend to shift outward and away from a raining cloud. For example, if a rain cloud is passing to your left looking upwind, you can expect a left shift from the outflow gust. After that gust, keep clear of the rain cloud because the wind will typically die afterward for up to an hour as the cell collapses, and until the previous prevailing winds return.

To illustrate this, I’ll use an example from a recent 49erFX Worlds medal race. Pre-race, winds were very light, around 5 knots, and we had many distinct layers of clouds with occasional rain, some clouds were lighter and higher and some lower and darker. In the final minute before the race, winds were barely raceable. Then, I noticed an area of much darker clouds approaching from the left with some spitting rain, and the right side of the course had whiter clouds that were a bit higher up. The darker clouds were approaching fast. I figured they would arrive within the next 5 minutes (just after the race started) and I prayed our sailors (on the US Sailing Team) could see this too. After the start, it was clear they had. They were the only boats going hard left. They got a massive left shift with enough pressure to launch them to the front of the fleet, which had mainly gone right in the old breeze. With it being such a short racecourse, they were able to hold their lead through two laps and won the medal race.

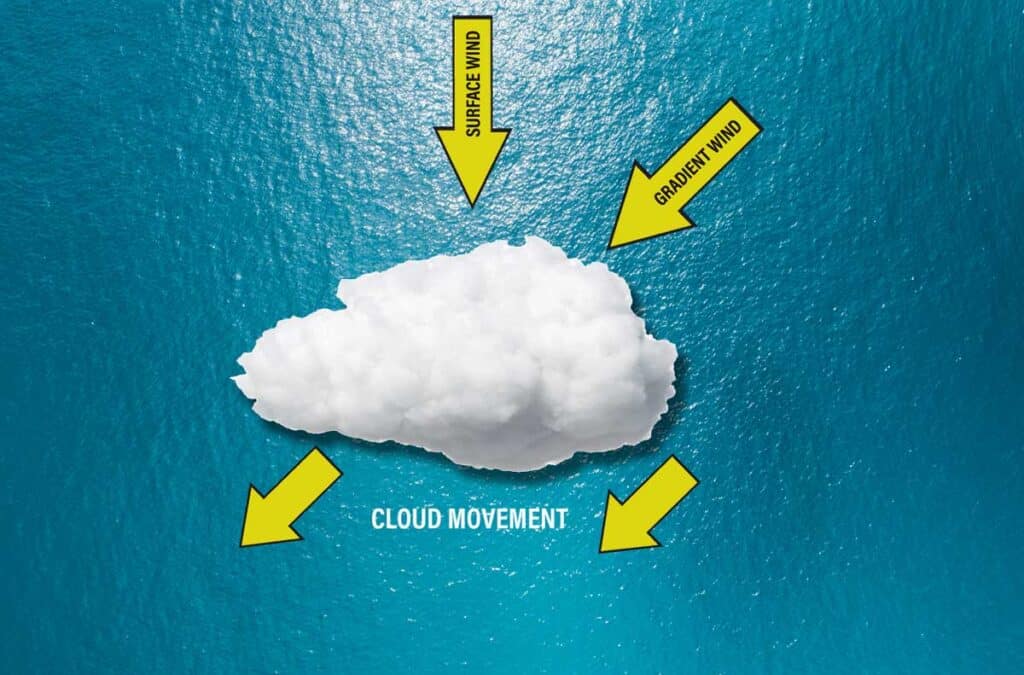

Practice navigating cloud-to-cloud

What should you do when you see a few puffy cumulus clouds heading downwind on your race course? Well, if you’re in the Northern Hemisphere, more often than not, the clouds will be moving downwind and slightly right to left across the sky. This is because friction over the water tends to shift the winds on the surface to the left. The winds pushing the clouds are not as affected by friction, and therefore are relatively right-shifted. This would, of course, be opposite in the Southern Hemisphere. For example, let’s say I notice clouds coming down the course on the run, and they are moving faster than I am. I predict they will overtake me and knowing they are moving right to left (looking upwind), I decide to jibe to port to let the clouds pass to my starboard, while I stay under blue skies.

We can also use this rule of thumb when we see low, flat, blanket-like clouds (stratus or stratocumulus) near or approaching the course. Due to friction, winds under large patches of clouds will generally be lighter and more left-shifted than the surrounding winds under clear skies.

Heed the big-picture forecast

Clouds from synoptic (large-scale) weather systems—fronts for example—indicate a new breeze arriving, if that is expected within the day’s forecast. To illustrate this, I’ll use an example from Miami a few winters ago. The forecast called for a light northerly wind to be replaced by a much stronger northwest wind. As we sailed out into Biscayne Bay, sailors and coaches were focusing on getting into upwind drills and checking the breeze as it came from the shifty direction of Downtown Miami, where skies were sunny. No one was looking behind us, toward the west. I made it a point to spin around and check for clouds in all directions, as I typically do.

I noted to the coach I was riding with, “I bet the wind will drop in the next 10 minutes and then get ready because it’s going to blow 15 to 20 knots.” As he looked at me, surprised, I just pointed to the horizon where we both saw the clouds and it then clicked—those clouds must be indicating the new wind.

If one were to look at a satellite image from that morning, you would have seen the large cloud bank approaching. But let’s assume you didn’t, and you only knew the wind was forecast to shift and increase. Noticing this cloud bank and how quickly it was moving before anyone else would have made a big difference for your next-race strategy.

The most accomplished sailors will attest that understanding and utilizing the wind around clouds significantly enhances your strategy. Mastering the wind around clouds is an art that requires a combination of observational skills, meteorological knowledge, and practical experience, so get out there and practice identifying and timing the clouds before your next race. In other words, remember to look up!