As a sailmaker, I sometimes feel like a doctor talking to an ill patient calling me with a list of symptoms, asking me—without a proper examination, mind you—to diagnose the ailment and offer a cure. Most of the calls from my “patients” come Monday morning, right afer a racing weekend. The calls go something like this, “We had great speed forward, but could not point with the rest of fleet,” or “I had tons of helm and could not keep the boat flat. I think my new sails are too full.”

Once I’m done listening for telltale clues I ask questions to come up with a diagnosis. “How tight was the jib halyard,” “Where was your jib lead?” “What model main were you using?” I will then ask if the customer has set up his boat according to the tuning guide that comes with each sail. Human nature being what it is, everyone answers: “Of course, I have!” From there, I mine into the details of the tuning guide and how it applies to their specific boat.

The difference I’ve found over the years between sailors in the middle of the fleet and those at the top is that the top sailors have learned, for their particular class, why the information in the tuning guide is there. Why, for example, you set up a J/24 always with a maximum length headstay, and why, in the Etchells class, two seemingly identical boats have mast rakes that vary by an inch or more, and yet both boats are fast. The best sailors are like chefs

who have gone through Le Cordon Bleu, learned to follow all the standard recipes, but are now creating their own variations because they understand how the basic ingredients go together.

In this first installment of a two-part series we’ll focus on getting beyond the tuning guide and developing the tools to really understand how your particular boat performs best. Think of it as putting aside the “cookbook” and getting into science of the recipe.

Let’s start by looking at the basics of most tuning guides—setting up the rig in the boat—and then proceed to the parts of the guides that include sail trim and how to get to the next level and make sail-trim decisions on the fly.

Getting a balanced package

The most basic requirement for having consistent boatspeed is a balanced helm. In its simplest form, a boat is balanced when the center of effort (CE) of the sails (geometric center of the sailplan) is over the center of lateral resistance (CLR) of the underbody of the boat (geometric center of the underbody). Anyone who has sailed a windsurfer knows there’s a spot where the mast is held in just the right position, fore and aft, which results in the

board sailing straight. Your keelboat or dinghy experiences the same thing.

When sailing your boat, it helps to remember that the CE and CLR are actually displaced significantly forward from their geometric centers. The CE shifts forward when sailing upwind due to the camber in the sails (assuming a standard sloop rig). A similar thing happens with the CLR, due to the camber in the underwater foils most boats have. It’s also helpful to consider that the CE moves aft as the apparent wind moves aft and we start heading downwind. This is why boats, when close reaching, tend to get loaded up on the helm until turning downwind, at which point the CE shifts forward to the geometric center. It is also why, in most boats, raking the mast forward downwind and reaching is fast. It helps to give more of a neutral helm, especially on a reach.

Almost all tuning guides I’ve read or written start with the absolute basics on to how to set up the boat, mainly positioning the mast. Usually, a few key numbers are there: mast rake, baseline shroud tension and pre-bend (static bend at the dock), mast-butt position, mast position at the deck, and spreader deflection, if the boat has swept spreaders.

These basic settings are the starting points on the road to really setting up your boat with neutral helm. But what the best sailors know is that all boats,

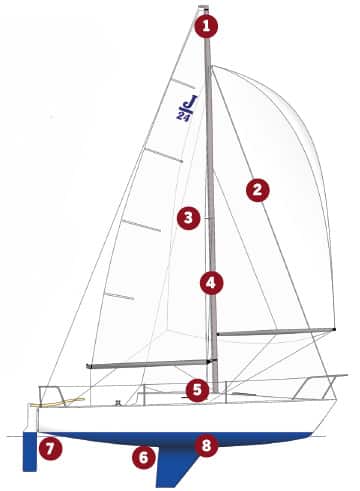

even strictly controlled one-designs, are not exactly alike. With keelboats, especially, the realities of mounting the keel, deck, mast step, etc., can add up to some major differences in boatspeed influencing factors. Afer you’ve followed your sailmaker’s tuning guide to the letter to get to your basic setup, carefully quantify the differences that may exist between your boat and some sisterships. Refer to the diagram below for a handful of important measurement points.

The diagram addresses the major variables that can influence how easy your boat is to sail and therefore how fast it will be, on average, around the track. Before looking at these variables, check your class rules about the amount of tolerance in each. Many of them, like mast stiffness, are unregulated, and in most cases, there’s enough of an allowance to be able to gain a significant advantage by carefully looking at them and optimizing your particular boat. It will take time and experimentation, but I can assure that by optimizing each one of these, in total, you will have taken very significant step to making your boat faster. You can now put the cookbook away.

Where the Differences Lie

Not all one-designs are created equal. Here’s eight common areas where differences from boat to boat may be subtle, but ultimately important.

1. Overall mast length: Assuming the forestay length stays the same, the longer the mast the more vertical it becomes, which reduces rake and helm. A shorter mast would mean more rake and more helm.

2. Forestay length: A longer forestay adds rake to the sailplan and increases helm. Conversely, you’d shorten the forestay to decrease helm.

3. Spreader angle: Angle the spreaders forward to reduce the tendency of the mast to bend under load, and to increase helm. If you have a very stiff mast, angle the spreaders back to help induce bend and lighten the helm.

4. **Stiffer or softer mast **(measure deflection and compare to others): A stiffer mast usually allows the main to set up fuller, which increases helm. A softer mast usually is easier for light winds as it pre-bends more easily to flatten the main in lighter winds.

5. **Fore-and-aft mast position at the partners **(keel-stepped masts) A mast that’s chocked further aft at deck will increase helm. Chock or move the mast forward at the deck to decrease helm.

6. Fore-and-aft keel position: Having the center of effort behind the center of lateral resistance gives the boat helm. The closer these two points are, the more balanced the boat will be.

7. Full versus thin foil sections: While not directly affecting your helm, foil-section thickness has a direct effect on speed. Generally, a fuller section

is better for lumpy conditions, and a thinner section is better for flat water.

8. Vertical rudder angle: Angling back the bottom of the rudder back increases helm. Conversely, angling forward decreases helm.