Inhaulers

For many years, most top racing boats had overlapping headsails. This overlap of the main and genoa slows the airflow between the two sails, resulting in power and boatspeed. But nowadays, many boats carry non-overlapping jibs that produce much less power, especially in light air. One solution to this power shortage is the jib inhauler, which is a purchase system that pulls the jib clew inboard, thereby narrowing the sail’s sheeting angle.

To understand how inhaulers affect your sail trim, let’s first review some basic principles. When sailing upwind in normal trim, a jib slows the airflow as it passes the mainsail’s leading edge (luff), which makes the sailplan more efficient, and the mainsail less resistant to stalling as it is trimmed to the boat’s centerline. As the jib is trimmed closer to centerline (i.e., with an inhauler), the airflow slows even further. The result is improved pointing, and ultimately, an efficient light-air trim.

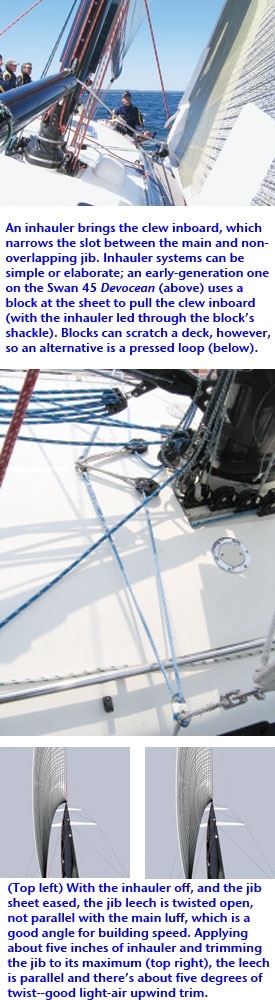

Boats with non-overlapping headsails normally have jib tracks that are angled anywhere from 8 to 10 degrees off the centerline of the boat. This angle creates a wide gap, commonly called the “slot,” between the two sails. With a wide slot, the jib is too far away from the mainsail to sufficiently slow the airflow. The inhauler reduces this slot. For maximum efficiency, the jib leech must be parallel to the luff of the main. When these two are parallel, airflow exits off the mainsail at the correct angle (not stalled or too open). When the air flows off the sail at an angle of 10 degrees to the centerline it’s thrusting the boat forward at a wide angle, but not as efficiently as at 8 degrees, or better yet, 7 degrees.

Certain boats, such the Farr 40 and the Mumm 30, are designed to sail with the jib set at 7 degrees. To make this happen, the jib clew must be pulled inboard so the top of the jib is twisting open and the bottom is pulled in parallel with the main.For an inhauler system to work, the jib clew must be at cabin height. And, if there’s a lot of inherent leech return (return is when there’s a belly in the leech and the exit of the sail turns in towards the centerline), inhauling will create excess drag and slow the boat. Remember, the greater the return on the leech towards the centerline, the more it works like an airplane’s flaps during landing-the resulting drag causes the airflow to really slow down, and in turn, backwind the main.

It’s helpful to have a small amount of return in light air; the jib will develop just enough power to provide feel to the helm without losing pointing ability. When the boat is at speed, it’s not necessary to have return to develop power. With a smaller and flatter jib, say a No. 2 or No. 3, return is unnecessary because there’s no need for it in heavier airs when these sails are used.

Installation and customization

If your boat doesn’t have inhaulers, and it’s something you’d like to experiment with, there are a few factors to consider: your current sheeting angle, your keel and hull design, your sail plan, and whether you’ll be able to install an inhauler system that works within your deck layout. With regard to sheeting angles, you’ll encounter performance problems if you start sheeting the jib tighter than the boat is designed for. In other words, if you’re pointing at a higher angle, and the flow over the keel is reduced, you may increase the leeway of the boat and slide sideways upwind.

If your standard sheeting angle is at 8 to 10 degrees (off your boat’s centerline), then you shouldn’t have problems inhauling an extra degree or two, so long as your keel and sail plan allow you to do so. One of the easiest ways to determine this is to look at the height of the jib clew off the deck. If it’s high enough, you’ll be able to set up the inhauler at the correct angle. If the clew is close to the deck, have your sailmaker re-cut it to allow you to inhaul.

When it comes to keel types, a narrow, slender keel with a short chord length can work well with inhaulers. If the keel’s leading edge is fat, the boat will be slow and sluggish, and it will be harder to get up to speed when you’re inhauled.

If you set up an inhauler, it’s critical that it pulls inboard at an angle perpendicular to the sheet. If not, it will increase sheet load or leech return. Other issues that need to be addressed are how the system can be worked into the deck layout; it will need strength in some areas, as the loads can be significant. Most inhaulers are set up on the centerline of the boat using a pad eye. For Swan 45 Devocean‘s deck layout (see photo), the inhauler is in a 2-to-1 system that passes through a block and then runs forward to a pad eye on deck. The pad eye is supported with a backing plate under the deck. Having the system come to a central point makes it easier to trim the inhauler evenly on both tacks, which is important because you want equal, repeatable settings from tack to tack.

Most racing boats lead the inhauler control line through a block on the cabin top and run it aft to a winch or purchase system on the top of the cabin. A basic setup is a simple 2-to-1 purchase leading to a 6-to-1 system from the pad eye. Smaller boats can get away with a 4-to-1 purchase that will have a line from the clew of the sail leading to the purchase system.

On smaller boats I’ve always used Spectra inhaulers, but on boats larger than 40 feet, Vectran is better because it will stretch less than the Spectra. When building my systems I’ve always used Harken blocks, but there are other companies that now offer complete systems; some of the best are from Diverse Yacht Services (www.diverseyachts.com).

Putting them to use

One thing I’ve always found when using inhaulers is that the crew and driver need to work more closely as a team; the ability to adjust the inhauler while the driver keeps the boat in a groove is an art. The driver must learn the fine art of pointing high while keeping the boat up to its polars. Certain boats with inhaulers, such as the Swan 45, are difficult to keep in the groove, and constant work by the crew trimming the jib in conjunction with the driver footing and pointing, working the boat through the speed builds and lulls helps the boat stay in the groove.

When trimming with an inhauler, there are rules of thumb. When the boat is starved for power, ease the inhauler a little to let the driver foot a little more until he’s up to speed. This means opening up the slot until the boat is back up to speed. If the driver keeps dropping speed, and can’t settle into a groove, move the car forward to round out the foot a little to make him sail lower. This builds power and helps the driver generate speed faster. You will need to ease the jib sheet when you do this to make the leech parallel to the main.

If the boat is not pointing, the foot may be too round, so flatten it a little by taking in on the sheet or easing the car aft. If the boat is going fast, but not pointing, take on a little more inhauler-up to the coach roof. This will be the limit on how much you can adjust the inhauler. Most of the time, if the boat is not in the groove, it has to do with the driver struggling to keep the boat sailing fast. If this is the case, and he is starved for power, the solution is to ease the inhauler.

This article first appeared as “Boatspeed” in our October 2006 issue.