At some point in every race, and especially in the top half of the beat, you’ll be faced with a seemingly easy decision: “Should I cross (or pass behind) this pack of boats, or should I tack and stay with them?” The decision, however, is rarely straightforward. There are a lot of variables to weigh before making the call, and often very little time to do so. The choice between a tack and a dip can make all the difference in how you get to, and out of, the top mark.

Leading back on the open course, by tacking underneath a group of competitors, takes patience and speed. Speed will lead to patience and allow this conservative tactic to work more often than not. As a big fan of conservative mid-line starts, I continue to work on this concept in an effort to sail consistent, low-risk races. No one situation on the racecourse will be the same, however, so the focus here is to provide a couple of helpful tips that will hopefully work, and give you higher top-mark percentages.

First, let’s revisit speed and patience. The two go hand in hand, but it’s always worth reiterating the point that solid, conservative tactics start with good boatspeed. There’s no way around it. As a team, make sure you’re committing the appropriate amount of time and energy into developing boatspeed; everything else will fall into place.

Now, back to the subject at hand. When determining where I am on the racecourse and whether to lead a group back, I weigh three factors in my decision-making process: time to layline, traffic management, and windshift.

Let’s first examine time to layline.

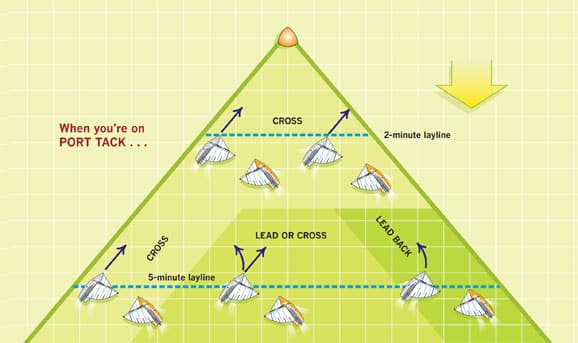

The closer I am to the opposite-tack layline (for example, on starboard tack approaching the port layline), the more likely I am to tack under the group. The reason is simple. Allowing a group of boats to get bow out on the long tack increases the chances of them passing you. Even if you can cross a group of boats, there is a 50-percent chance of being passed because of a windshift favorable to them. If I am within 2 minutes of reaching a layline, especially the port-tack layline, I will most likely tack underneath and lead a group (or even a single competitor) toward the top mark. The likelihood of being passed because of a shift is small, and, realistically, if the shift goes toward the boats that are to the right or left, they were probably ahead already.

Otherwise, if I’m close to the top mark on port tack and looking to get in line, I won’t lead them back. This would be in situations in which I have less then 2 minutes sailing time to the top mark on the starboard-tack layline.

With more than 2 minutes, there’s a greater chance of either overstanding the top mark or sailing slow in the starboard parade, so I’d be inclined to tack underneath and lead back on an inside track, looking for an opportunity to get in line closer to the mark. In a persistent shift, rather than leading a group back, I’ll cross and set up to windward to be in position to take advantage of the shift.

The decision to lead back or not is most difficult when you’re halfway up the beat. When leading a group, I try to position the boat as close as possible to the pack, but still bow out. If you look at it from the perspective of sighting from where the helmsman sits, you always want the helmsman to turn his head to windward and see the windward boat just over his aft shoulder. The closer you are to the windward boat, the more disruptive your position will be. However, I never put myself so close that it prevents me from sailing my preferred mode.

What happens if you have to deal with a persistent windshift and traffic management? There’s a balance. If I’m approaching a group of five (it all depends on fleet size) or more boats, and I’m on the lifted tack with the times even to either layline, the decision is easy: sail the shift, even if you have to dip all five. Make every dip close! While dipping is no fun, as long as you’re in phase with the wind, you will be sailing the shorter distance to the top mark and against the traffic. Be careful in this scenario, however, because if you are truly on the lifted tack, then you can expect one of these other competitors to know it and tack on you. In the same scenario, and if the shift is even (meaning not headed or lifted), I will balance the traffic versus being able to sail my boat’s mode because bad traffic is just as bad, if not worse than, a bad shift.

Also consider every boatlength that you dip as a step down the imaginary ladder rung. The top of the ladder gets you to the top first or in the lead group. I use this concept to lead back. If, by tacking under a group in the middle of the course, I can go into a holding pattern, sail my mode, and wait for the next obvious decision, then I have, in effect, kept myself on the same ladder rung as the lead group.

In the middle of the course, with your bow in the front row, even though boats are getting leverage toward the sides, I am essentially using my boatspeed and patience until a higher percentage move becomes obvious. The most important point to consider with the ladder rungs as an example, is tack loss. Every tack costs boatlengths, so you must balance the tack loss against the dip loss. The best tacticians will do as little as two tacks on a beat and as many as five with the same result. So be mindful to not tack yourself up the middle of the course in an effort to play it safe as that won’t work either.

While we’ve discussed traffic already, I’d add that traffic on the starboard-tack layline must be avoided like the plague. If you have the option of either overstanding or tacking underneath the group and weaving through a couple of boats at the mark, take the latter, as doing so will keep you in the game. Overstanding by five or six lengths is succumbing to the inevitable. If, by tacking under the group and leading out of the right-hand side you have avoided traffic and kept your nose clear, there’s a good chance you are in a better spot at the top mark than had you overstood the layline.

Pro Tip: Leading on the Run

If we’re talking about a gate mark or the bottom of the course, I always prioritize clean air, wind shifts, and the direction I want to be going—in that order. Sometimes, you have to go the wrong way for clean air, but that is a gain over somebody going the right way, but sailing in dirty air.