Unless you’re a graduate of the Buddy Melges School of Racing, where you start first and then extend, sooner or later you will be looking down the wrong end of the barrel when it comes to maintaining clear air on the run. While it’s important to keep your air clean downwind in any type of boat, not doing so in a boat with a sprit-mounted asymmetric spinnaker can be especially costly. And that goes double for a-sail boats with the ability to plane.

To determine the best way to escape a windshadow on the run, you first must be able to figure out the windshadow’s location. This requires understanding the apparent wind angles for the boat you’re sailing and the boat you’re sailing against. On boats with asymmetric spinnakers, the true and apparent wind angles are ofen widely divergent when sailing downwind.

On lightweight, planing keelboats, such as the Melges 32, and lightweight dinghies, such as the 49er, the tremendous downwind boatspeed moves the apparent wind well forward of the true wind. These boats go much faster at hotter (i.e. closer to the wind) angles. In fact, in the Melges 32 class, few people sail with full-size spinnakers. A slightly smaller kite, with less drag, will be faster at a slightly higher angle and result in better progess (velocity made good or VMG) toward the leeward mark. In planing boats, just a few more degrees of height can create a significant difference in speed.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are heavier, non-planing sprit boats, such as the J/120. The speed differential between a J/120 that’s sailing a low angle and one that’s sailing slightly higher is usually quite small. These boats carry large asymmetric spinnakers. By easing off the tack line, heeling the boat to windward, and rotating the kite from behind the mainsail, you can sail quite deep without losing much speed. The true and apparent wind angles will be further apart than on a boat with a symmetric spinnaker, but not by a lot.

The other factor to consider is the general range of a windshadow. A good rule of thumb is that a windshadow will extend as far as 10 boatlengths to leeward of a boat in light air and as little as six boatlengths when it’s windy. The most accurate guide to the location of your opponent’s windshadow is the Windex on the top of his mast. However, that can be hard to see, or he may not have one. It’s often easier to use your Windex (or shroud tell tales). And your Windex provides the key information to how you should react.

Sight off your Windex and see where it points relative to your opponent’s sail plan. If your Windex is pointing close to the center of your opponent’s sail plan, then you can safely assume he has you in his sights.

If your Windex is pointing in front of the luff of your opponent’s spinnaker, you’ll be in clear air. Since your breeze is coming from ahead of the other boat, this situation is referred to as “air ahead.” If your Windex is pointing well aft of the leech of your opponent’s mainsail, you’ll be in clear air as well. Conversely, this is known as “air behind.” Knowing whether you’re covered, have air clear behind, or have air clear ahead will help you determine your next move.

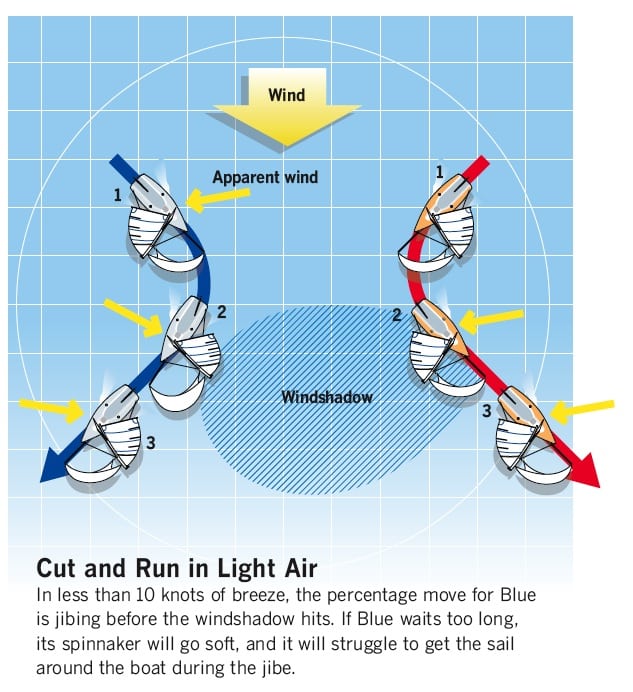

Light air

If you get jibed on in light air, don’t bother trying to live there. Struggling to sail in bad air when the wind is under 10 knots will be more detrimental than jibing away. With a symmetric spinnaker, you have a better chance of living in disturbed air, but with a sprit-flown asymmetric, clean air is more important. If you see a boat jibing to blanket your wind, jibe away before their dirty air gets to you, while you’re still in the “air behind” position, and while your spinnaker is still full and pulling. If you wait until you enter your opponent’s windshadow, your spinnaker will get soft, it won’t fly away from the boat when you cast off the sheet, and you’ll have a poor jibe. If there’s any doubt, jibe out, and do so early.

Medium air

In 10 to 15 knots of wind, the game changes considerably. Now, it depends on the position of your opponent’s windshadow once he jibes on you. If you don’t want to jibe, you have three options: You can sail lower, sail your VMG, or heat it up. Which of these is the best option depends on exactly where your opponent’s windshadow falls. If they hit you square on, you’re always going to lose, and it’s a real weapon for a covering boat that has great crew work.

Regardless of the type of boat you’re sailing, if your opponent plants you squarely in the middle of his windshadow, your best option is to jibe away.

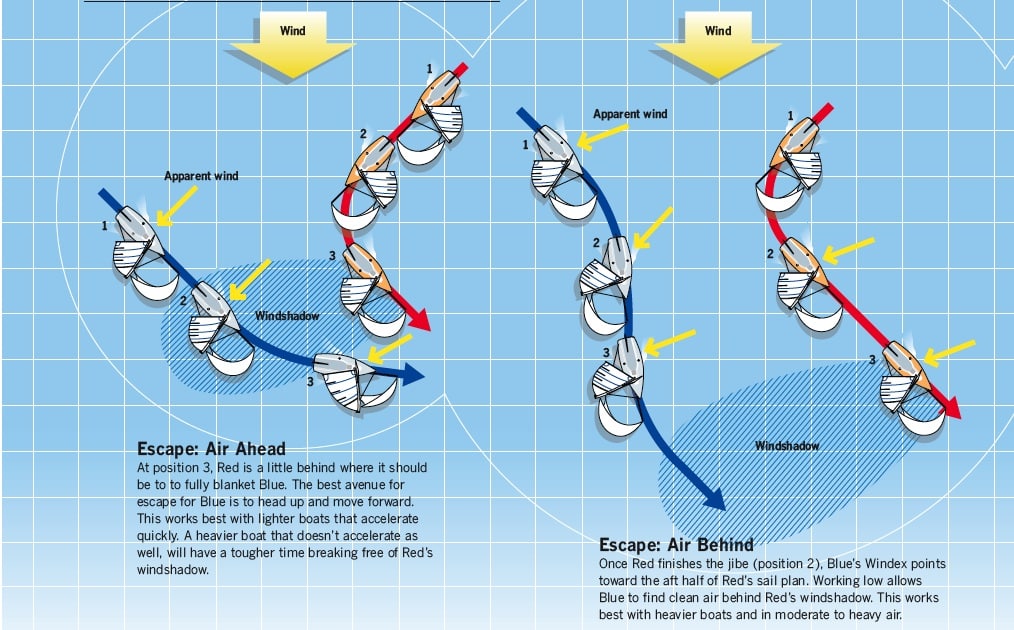

If your opponent is a little slow or late on the jibe and hasn’t hit you perfectly—you can tell this because your Windex will point more toward the bow of his boat than the middle—put the bow up immediately, especially if you’re in a lighter boat. Your speed will increase, your Windex will rotate forward, and you’ll move into a position where you have “air ahead.”

If they jibe on you, and your Windex points to the aft part of their boat, suggesting that you’re in the aft half of their windshadow, it can be tempting to try to live there. However, on a lightweight, planning asymmetric boat, as you sail through puffs and lulls, you’ll gradually end up losing your lead. When your opponent gets a header or puff, they’ll drive off, and since they’re to windward, they’ll be the first to get that new wind direction or speed. So they’ll be driving off while you’re still sailing on the old wind, enabling them to further close the gap and obstruct your breeze. At some point, you’ll have to sail in their wake. It can be a really hard spot to be in. More often than not in a planing boat, if you find yourself in this situation, jibe away while your opponent’s windshadow is still in front of you and you are “air behind.”

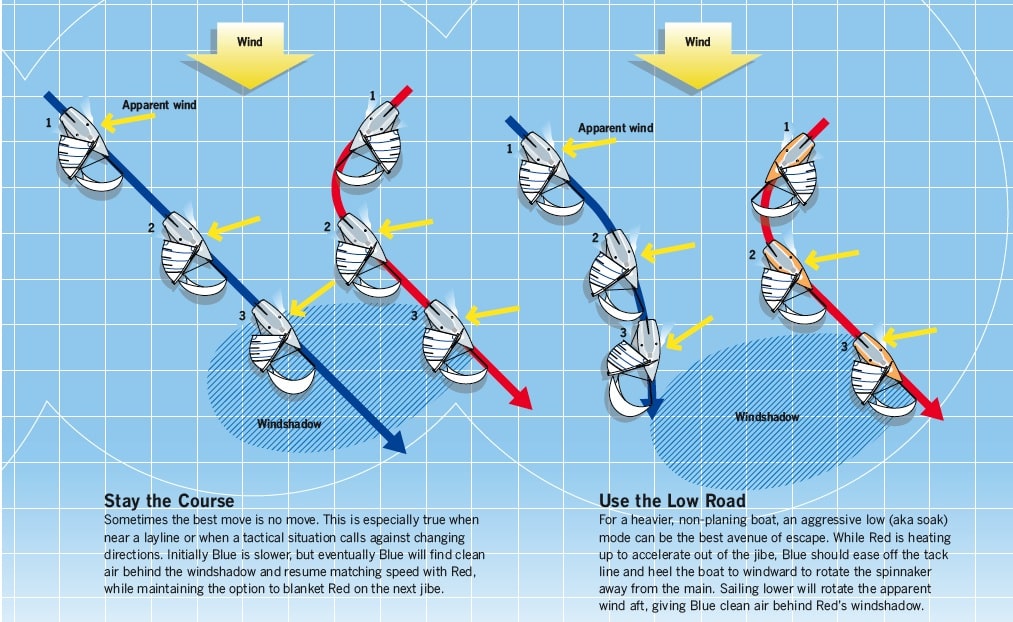

On symmetric or heavier, non-planing asymmetric boats, holding your optimum downwind angle works best when you find yourself toward the back edge of your opponent’s windshadow. You will go a little slow for a short period of time before you run into the clean air aft of the windshadow. At that point, you should be able to match your opponent’s speed. The loss created staying on the same jibe and enduring a bit of bad air will be less than the distance lost through jibing.

Heavy air

On a 49er or Melges 24, the mantra in heavy air is to always keep the boat going fast. If a boat jibes on you, and their windshadow hits you, you’ll stop, and your competition will plane away. The first choice is to put the bow up to keep the boat planing. If that’s not an option, you must immediately jibe away.

If the covering boat hits you square on, it’s almost guaranteed that, no matter how you deal with the windshadow, you’ll lose out. The trick is to minimize that loss.

On symmetric and heavier asymmetric boats, the windshadow becomes less important once the breeze gets above 15 knots. The heavier and slower the boat, the more likely your best move will be no move. If you get jibed on or rolled, keep sailing your angle. By sailing straight, your opponent will get in front of you, and eventually you’ll start sailing the same speed as the other boat. If you’re in a J/120, for instance, and you get jibed on, it’s tempting to reach up for clear air. The problem is that displacement boats generally don’t go much faster on hotter angles, so you won’t gain any distance forward. In the long run, you’ll lose VMG and put yourself deeper into his windshadow. Rarely would you want to immediately jibe away, because the windshadow is not that effective. It’s best to wait for the windshadow to move ahead of you and sail with air behind while controlling your opponent from a leeward position.

This article originally appeared in the Tactics section from our June 2011 issue.