Keen racing sailors spend countless hours and effort in the elusive quest for top results, but once they reach the top, or become very close, many struggle with the most difficult part—transitioning from getting there to staying there. A recent conversation between SW’s resident racing doctor and a top-level coach reinforces the challenges of staying at the top of one’s game.

Doc: Hey there, coach. How are those 420 kids of yours doing?

Coach: They’re really jumping ahead. Each week, you can see they’re really starting to understand this racing thing, and as they’re stepping up, they’re getting more enthusiastic and committed.

Doc: I’ve been hearing good things about your program.

Coach: Yeah?

Doc: I was having a chat with one of the parents. They were saying how the whole attitude of the squad is getting more positive, and the kids are having a ball.

Coach: Actually, the success is a bit of a two-edged sword.

Doc: How do you mean?

Coach: One of the parents races on a J/24 and wants me to coach her team leading up to the nationals next year.

Doc: That’s a good thing, I guess?

Coach: Well, I guess. I mean, they’re a pretty hot team. They came third a couple of years back.

Doc: … Yes? You’re not sounding very excited.

Coach: Cards on the table? I’m worried. They probably know more about sailing than I do—particularly the J/24. What can I teach them? I don’t want to come across as half-baked.

Doc: You seem to think you need to teach them stuff?

Coach: How can a coach be credible if the team has already outgrown the coach’s knowledge base? … What are you looking at me like that for?

Doc: What was the last class you sailed seriously?

Coach: 470 Olympic trials. But that was a few years ago now.

Doc: But you were pretty good then, weren’t you?

Coach: Yeah, we were up there.

Doc: What was it you were wanting from your coach building up to the trials?

Coach: Murray was a great coach. Never got in a flap—always kept our eyes firmly on the ball. When things felt like they were starting to crumble or felt pointless or directionless, he was able to help pull us around.

Doc: But what were you working on? Roll tacks, mast rake, pin-end starts …

Coach: Honestly, I don’t remember. We did do a lot on starts, and hours of speed testing. But most of the time, I guess, we were nutting through the issues of the moment. Working out how to do things—everything—that much better.

Doc: You’d made the switch from trying to attain a level of competence that would get you into the game, to refining and sustaining that performance. It’s an important shift. You were no longer working on the things that the 420 kids are working on—like trying to do even occasionally a world-class tack. You could do those already. You were working on delivery—exquisite, reliable delivery of what you already knew you could do. You had moved from “attain” to “sustain” training mode.

Coach: You’re talking about the difference between the 420 kids and the J/24 crew, aren’t you?

Doc: A coach’s job with an elite-level team boils down to only a few things, and teaching them things is the least of them. The first is what you said Murray did for you: provide a way to re-orient yourself when things go wrong. It’s a combination of providing an independent ear, a solid problem-solving approach, and that credible and rock-solid support and belief teams can rely on when the chips are down.

Coach: You’re saying the coach is like your best work colleague?

Doc: Partly. I guess I’m saying that top coaches and crews both have fairly high levels of expertise. A big part of a top coach’s value is in the relationship with the crew, rather than expecting the coach to always have the answers. But there’s a second part. Top coaches hold their teams responsible for focusing on perfecting performance. It’s not all about constantly trying new things; it’s about refinement at a very high level—being able to do a world-class tack every time.

Coach: You’re saying that a good coach is a taskmaster—“get out there and do 100 tacks before I let you off the water?”

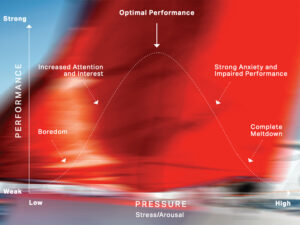

Doc: Yes, there is a taskmaster element I suppose, but most serious teams set that level themselves. In sailing at an elite level, world champion performance does not automatically result in a race win. How many times has the winner of a major regatta not won a race? World-champion performance comes from the disciplined delivery of the behaviors that maximize your performance at any given moment—and doing that at all times. I guess you could frame “mental toughness” in those terms. It’s about resilient and committed adherence to performance behaviors in the face of powerful forces of distraction. The coach helps the team to embed and perfect knowledge and behavior patterns that result in performance. Put another way, he redefines success for the team.

Coach: Now you’ve lost me.

Doc: At an Olympic Games, everyone is good. Everyone can sail at that phenomenally high level. But a good number of teams don’t—it’s not that they can’t, it’s that they don’t. The difference at that very top level is that a winning team never drops off its game, no matter how tough the conditions get, or how stressed the sailors feel. They retain a laser focus—not on winning, but on “performance”—doing the things they know (through hundreds of hours of practice and racing) make the boat go fast and head it in the right direction. The also-rans get distracted, do a sloppy tack or miss a shift, or worse, start to get creative.

Coach: Get creative?

Doc: They respond to the “this ain’t working” monster, who’s mantra is, “We have to do something different.” This eats away at the sub-elite crews because they haven’t yet built the knowledge and confidence to really know what works. Even top crews can get caught because the distractions and emotional charges drag them toward panic and away from what they’ve spent hours learning.

Coach: … Cornersville?

Doc: A classic example! Shooting a corner to get back into the race, even though everything you know is screaming, “This is not smart.”

Coach: What goes on there? Why is that attraction so powerful?

Doc: There are two parts to the answer. The first is that, at times, the thought of not winning is so painful or threatening that we’ll risk anything to avoid it. The other is that the radical creative risk just might work. It’s like what psychologists call “variable-ratio reinforcement schedules.” If you want to condition a person to do a particular behavior, provide the reward he or she craves, but don’t provide it all the time. Do it inconsistently. Then, when the reward doesn’t appear, the person will try again because “maybe it will work this time.” Sometimes it does, so the person keeps behaving in that way. The pull from these two monsters is incredibly powerful, and it pulls top sailors away from doing the things that race the boat well.

Coach: So to coach a top team, help the crew commit to doing what they already know how to do?

Doc: That, and continually striving to improve everything incrementally.

Coach: I’m going to be brilliant.