Charlotte Rose, a two-time youth world champion and US Sailing Team athlete, has boathandling skills that are off the charts, which gives her the ability to quickly shift left or right on the starting line to get into an optimal position. While observing her at a recent clinic, I learned that she has four key starting moves: high build, double-tack, half-tack and reverse. After watching her execute these moves with ease, I wondered how effective they’d be in boats other than ILCAs, so I brought them to the 2023 J/70 Worlds. My teammates and I spent a few days practicing them, and discovered that they worked well, even in a J/70. These four approaches can be used in almost any small boat—and in bigger boats, to a degree.

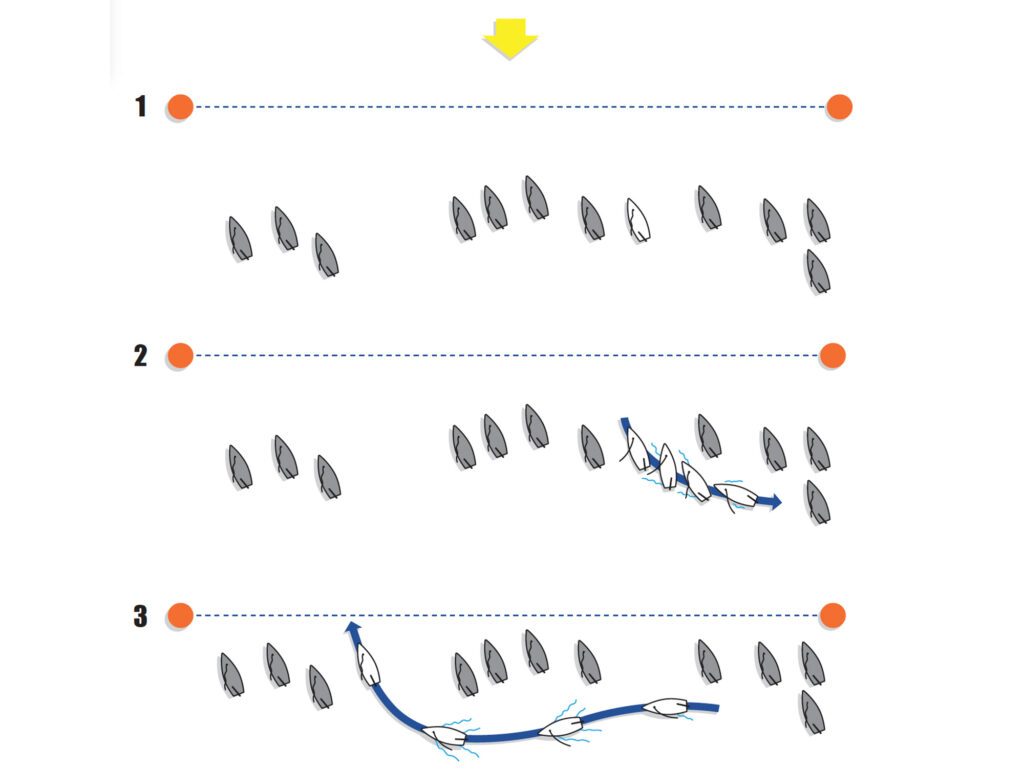

The High-Build Start

The high-build approach is powerful in medium to strong winds, when you’re on your final approach and you want to crowd the boat above you to create space to leeward. The setup starts by positioning your boat close to the boat above you and, with sails fully trimmed, steering just above closehauled. Be careful to keep the boat moving slowly through the water to prevent stalling. After sailing high and slow and creating space to leeward, just before the start, rotate the bow down and leave the sails fully trimmed. The boat instantly heels over and feels powerful. Then bear away 5 degrees or so, and ease the sails a bit to go for full acceleration. If it’s windy, you need only to turn down to a closehauled course. The boat will get up to speed quickly because there’s plenty of power in the sails. Because you’ve maintained flow across your blades and sails throughout, acceleration will happen fast and require less of a bear away. If you bear away less than those around you, the space to leeward will be bigger and the boats to windward will be unable to bear away to full speed.

There are a few important subtleties. Keep both sails trimmed, and use the jib as your guide. Head up until the front of the jib starts to backwind—usually one-third to halfway back—and the boat will flatten. The key is to keep the boat flat. To maintain the high and slow sailing, trim the sails in and out. For example, if the skipper is having to push too hard on the tiller because the boat wants to bear away, ease the jib and trim the main. This helps the boat continue to track forward. If the boat wants to head up, trim the jib and ease the main.

At the J/70 Worlds, the wind was mostly 12 to 18 knots—perfect conditions for high-build starts. It doesn’t work well in light air, because in these conditions, you need to keep the speed on and also bear away a fair amount to properly accelerate. Also, if you try to sail too high and slow in light air, the boat nearly stops, and it takes forever to get moving again. But in 8 to 9 knots or more, the high-build is a must-have in your tool box.

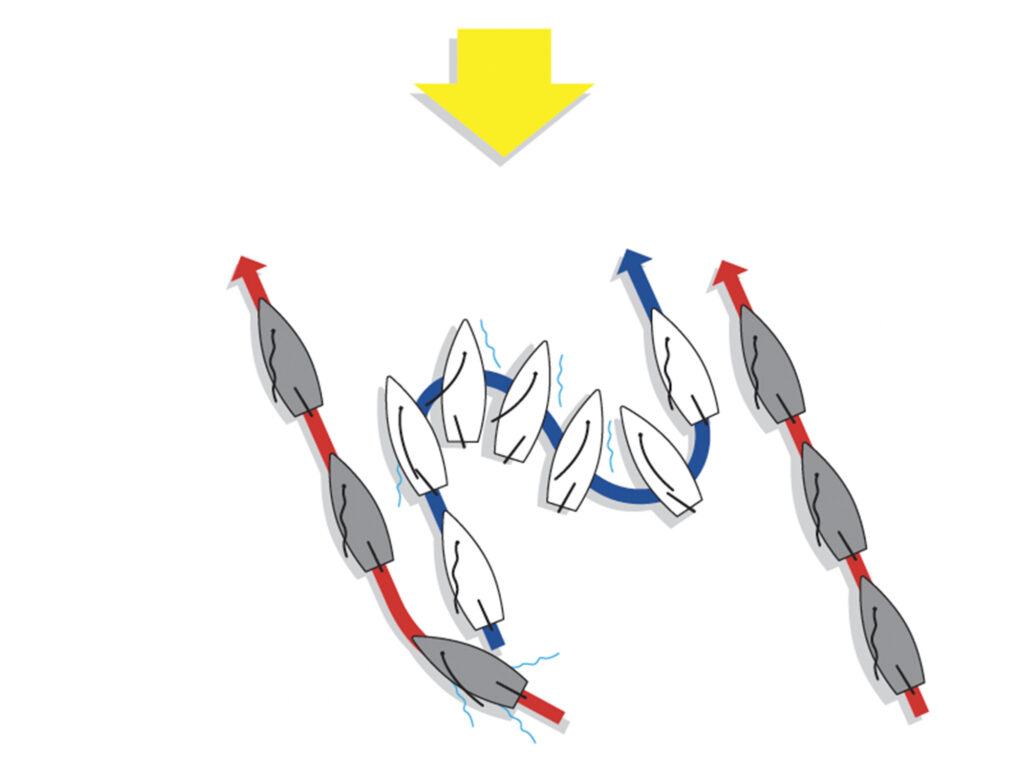

Double-Tack Reset

The double-tack is another powerful move that’s underutilized. It allows you to create a massive amount of space to your left while filling space to your right. Basically, it’s two quick tacks, first to port and then to starboard, but there’s more to it than that. International 470 gold medalists Matthew Belcher and Will Ryan were masters of the double tack. They got it down so well that they could do it in the final 10 seconds and, in their second tack, would come out racing. Doing it in the final few seconds and with perfect timing also meant that if the boat to their left tried to match them, that boat would be late to start.

Use a double-tack whenever there’s space to your right and someone comes from behind and hooks or overlaps their bow just to leeward of you, or if a boat comes in on port tack and sets up in a lee-bow position. It’s a quick way to get separation and reclaim a hole on the line. On the J/70 or the Etchells, my teammate, Erik Shampain, audibles if the double-tack is an option. Whenever things are getting tight and we need an escape route, Shampain says to me, “Double-tack open,” and we roll into a tack, sail for as long as we need to, and then tack back.

Most people feel as if they have to have a lot of space to do a double-tack without fouling the boat to their right, the windward boat. In the clinic, however, Rose could double-tack in the tightest space I’d ever seen. When I asked her how she did so, she said that the key is a normal first tack, such as a roll tack in a Laser, and then an instant tack back onto port with no roll. Doing the second tack as a roll tack is OK if you are feeling late, but a flat tack allows you to turn in a tighter space, and you don’t advance on the starting line.

You need a bit of speed to begin a double-tack. Don’t try it from a stopped position. If you have room and want to sail for a length or two before tacking to starboard, you can. A subtlety to the double-tack is that when you complete that first tack, come out deep, aiming behind the boat to your right, which might make them think that you’re going to go behind them. Then, when you tack back, you’ll end up overlapped with them, with bows even. They’re now “locked” so that their bow is not free to hook you, and you’ve secured a nice hole to your left.

Another basic rule of thumb is that if the boat to your right double-tacks, match them. When they tack back, lee-bow them. You’ll have created a huge hole, and they won’t have one.

There are other purposes for a double-tack and considerations, other than just closing the gap between yourself and the boat to your right or separating from the boat to your left. If you sense that you’re early, tack, dip really deep to burn off time, and then tack back. If you’re late, tack and sail upwind, then tack back again, fully racing upwind. If the pin is favored and you need to close distance on the line, for example in a last-minute left shift, the port-tack part of the double-tack will help you close distance on the line because that tack is more than 90 degrees to the line. If the boat is favored, when many general recalls happen as closing speeds are high, and you need to kill time, spend more time on port tack when doubling because it’s closer to paralleling the line, and you will kill time. For those scenarios, it comes down to being confident with your time on distance and your closing speed on the line.

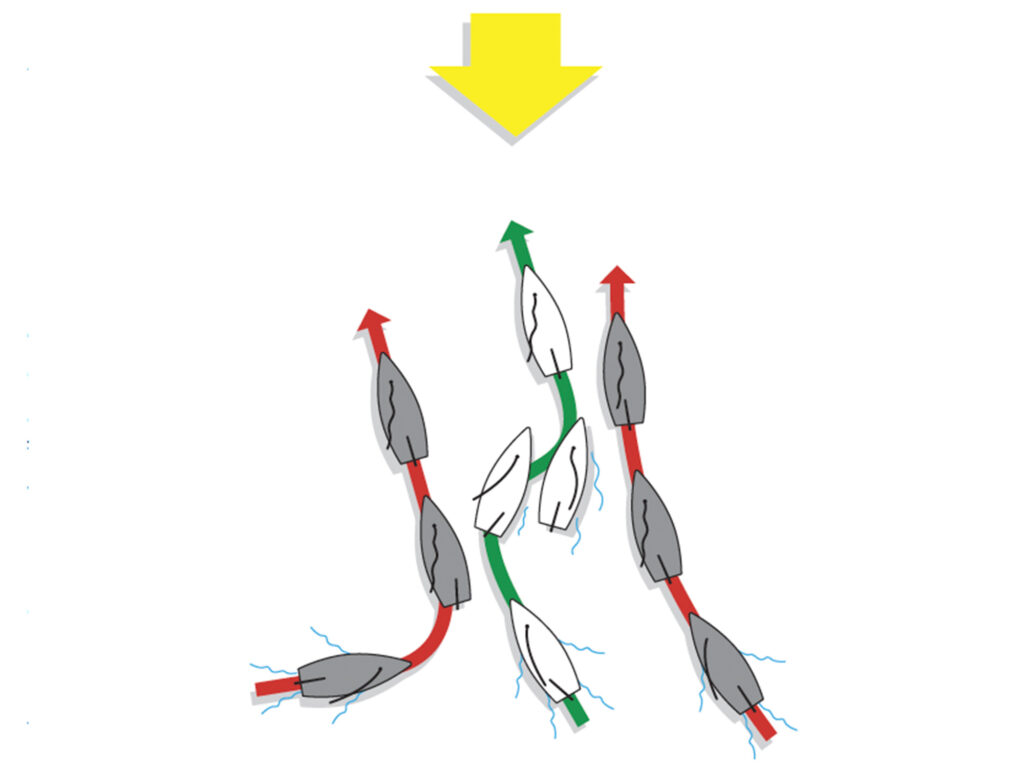

Half-Tack Reset

A half-tack is used when there’s not enough space to your right to do a double-tack. It works best in light and medium winds when you have speed.

Let’s say there’s a port-tack boat coming your way, and they’re likely to lee-bow you, and there’s a boat just to windward of you. Rotate your bow down, aiming just above the port tacker’s bow, and sail at them, which increases your speed. As you anticipated, they tack just to leeward of you. If you do nothing, they’ve stolen any space you’ve created to leeward, and you’ll be out of luck for this start. But, with your increased speed, do a half-tack, heading up and trimming your sails in, and sail about head to wind or maybe a touch past. Leave the jib in to the point where it backwinds. On an ILCA, the skipper can put their hand or left shoulder against the boom, pushing out a foot or so to backwind the main for just a few seconds. The backwinded sail pushes your bow to the right, opening up space between you and the boat that just tacked to leeward of you and sliding you closer to the boat to your right. Again, be sure you have speed going into this. In small boats like ILCAs, it helps to pull up the daggerboard to help the boat slide. In keelboats, we obviously leave the keel alone, but backing the jib really pulls the boat to the right, helping it slide or track toward the boat to your right. Be careful with this move, however, because you are considered a “tacking” boat. As long as you do not hit the boat to your right, you are fine. Once you’re close to the boat to the right, cut/release the jib, and rotate the boat back down to starboard closehauled to avoid a rules infringement.

To prevent tacking, the skipper must fight the helm, pulling the tiller toward them, keeping the boat gliding at either head to wind or slightly past head to wind. A more common move in the start is to shoot head to wind to get space to leeward. That’s fine, but this backing of the sails adds the slide to the right. While doing a half-tack, or as the ILCA sailors call it, a “slide,” keep the boat flat. The crew might even have to hike on the port side, the jib side, while the jib is backing, especially in medium winds. As the boat slides to windward, you can open up about a half-boatlength on the boat that just tacked beneath you. Now you have a hole to accelerate into. As your speed diminishes, uncleat the jib. We use the command “Cut!” The jib luffs, the skipper rotates the bow down to closehauled or slightly below, and we’re off.

The half-tack doesn’t work well in big breeze, because it’s so windy, you might not be able to keep the boat from tacking with a backed jib. And if it’s really choppy, you risk losing your speed if you smash into a wave during your slide.

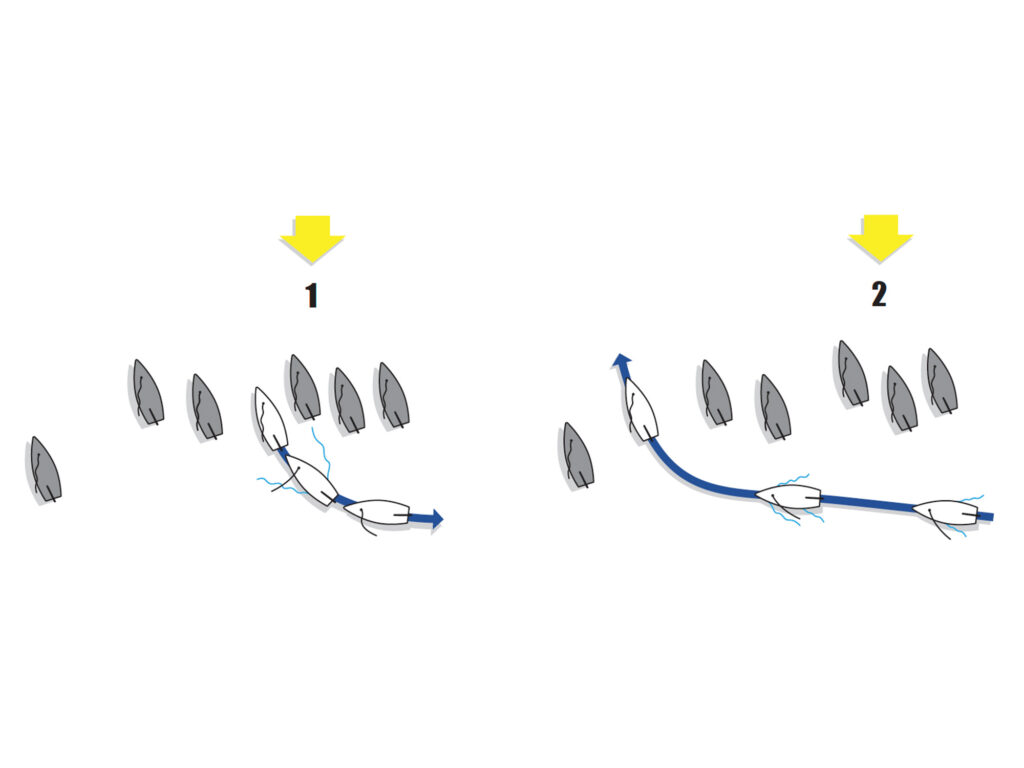

Drop it into Reverse

Let’s say you have boats close to leeward of you, and you realize that they’re going to prevent you from accelerating because there’s no hole for you to drive off into. Nor is there room for a double-tack or half-tack. The solution is to reverse out of there, backing up until your bow can clear the transoms of the boats around you, and then reach off and find a better place to start. It’s a great move when you really have no other options. Because the leeward boat is probably luffing you, you’re pretty much head to wind anyway, so you’re in a good position to start the reverse.

The most important part of this is to recognize early enough that you’re in a tough spot and need to get out of it. Otherwise, you won’t have enough time for the reverse. In a J/70, it might be with 60 to 90 seconds left; in an ILCA, it’s probably around 45 seconds. The technique starts with pushing the boom out just until the boat starts to reverse, then release the boom and let the sail luff. This point is where a lot of people run into trouble. Rose taught me not to hold the boom out very long. If you hold it out too long, it might cause the boat to tack, and you could lose control of the bow. Also, briefly holding the boom out keeps the boat from going too fast in reverse, which will make it difficult to stop. Again, your goal is to start the reverse to get your bow free, then sail somewhere else.

Steering backward takes time to learn. The tiller loads up, wanting to slam to one side or the other, and the boat will be more responsive to helm movements, so keep the tiller as close to centered as possible, and keep weight adjustments subtle. It will help to hold the tiller or hiking stick firmly in both hands. Once your bow becomes free of the boats to leeward of you, turn the boat down, away from the wind, and you’re now free to reach to the next open spot on the line. Remember, the whole line is open to you; you can exit to starboard or port.

The “bail out and sail somewhere else” technique works well because it’s better to be going fast in the final minute than to have no good option for accelerating because someone’s close to leeward. That’s death. If you bail and start reaching, you have a much better chance of pulling off a good start than if you just sit there in a tough situation with 40 seconds left. Typically, everyone else is bow up, going half-speed, while you can be reaching down the line with pace, searching for your next spot. And when you do find your opening, you can shoot into it with more pace than the boats around you.

We did a couple of scramble starts like this at the 2023 J/70 European Championships, which we won. Both times, we found a gap in the final 20 seconds, sailed into it with pace, and were able to tack and cross the fleet within 30 seconds after the start because the pin was so favored. You might call that lucky, but we were following a basic rule: When you feel like you’re in trouble, bail and go as fast as you can.

The beautiful thing about these four moves is that they not only help you create a gap, but they also give you more of a lateral game that you might not have otherwise. Practice these moves so that you’re good at them, and make sure you have the mindset of trying to find open space. A good practice drill is to try to sail a full lap around a stationary mark without tacking. We tried it in an Etchells once, and we actually pulled it off. Start by sailing by a mark on starboard tack, leaving it to port, with speed. Shoot head to wind, and do a half-tack. Let the half-tack glide you above and to the right of the mark. Then release the jib, let the boat slow down, and go into a reverse. Once you’ve reversed past the mark, kick the stern out so that you’re now on a starboard reach, and sail back around to the port side of the mark. You’ve now done a full lap around the mark without tacking. It’s also a great drill to practice slow-speed maneuvers. Try it first in 5 to 12 knots.

With these four starting-line moves, the next time you’re in a crowded spot in the final minute and half and don’t feel like you’re going to get a good start, you now have the option of positioning your boat somewhere else. As my high school students say, “Make your momma proud; don’t start in a crowd.”

As a multiple class champion and longtime coach, Steve Hunt has now expanded his coaching services to include virtual coaching at stevehuntsailing.com, a site created for the racing sailor to take their skills to the next level. With video tutorials and in-depth insight, Hunt and other top-level sailors aim to help sailors improve their speed, sail smarter, and improve regatta results—one race at a time.