Finishing properly is too often overlooked, even by the top sailors. After all, it’s easy. All you do is sail between the committee boat and the mark, wait until you hear the horn, and head for the barn. By the time you’ve reached the finish, the race has been decided anyway. Compared to the hectic decision-making time of the start, that shifty first beat and those crowded mark roundings, finishing is like hanging up the phone after making a call—it just happens!

But what about when several boats cross the line overlapped? In one race at the 1979 Soling Worlds, 17 of us finished overlapped on a run. It certainly paid to finish at the right end of the line! Or how about racing in handicap fleets? You may be crossing the line by yourself, but often every second counts. I once won a handicap race on a 26-footer by only three seconds after 127 miles; if we’d sailed half a boat length more out of our way we’d have been second.When approaching the finish, there are several tricks to get yourself across the line as quickly as possible. As usual, no hard and fast rules apply; every race ends differently, and good judgment must prevail. For instance, you wouldn’t tack away toward the better end if that meant splitting from a boat you were covering—unless, of course, there were other boats close behind heading for the proper end. There are, however, some general rules to obey when competitors are close or when you need to stop the clock as soon as possible.

Upwind Finishes

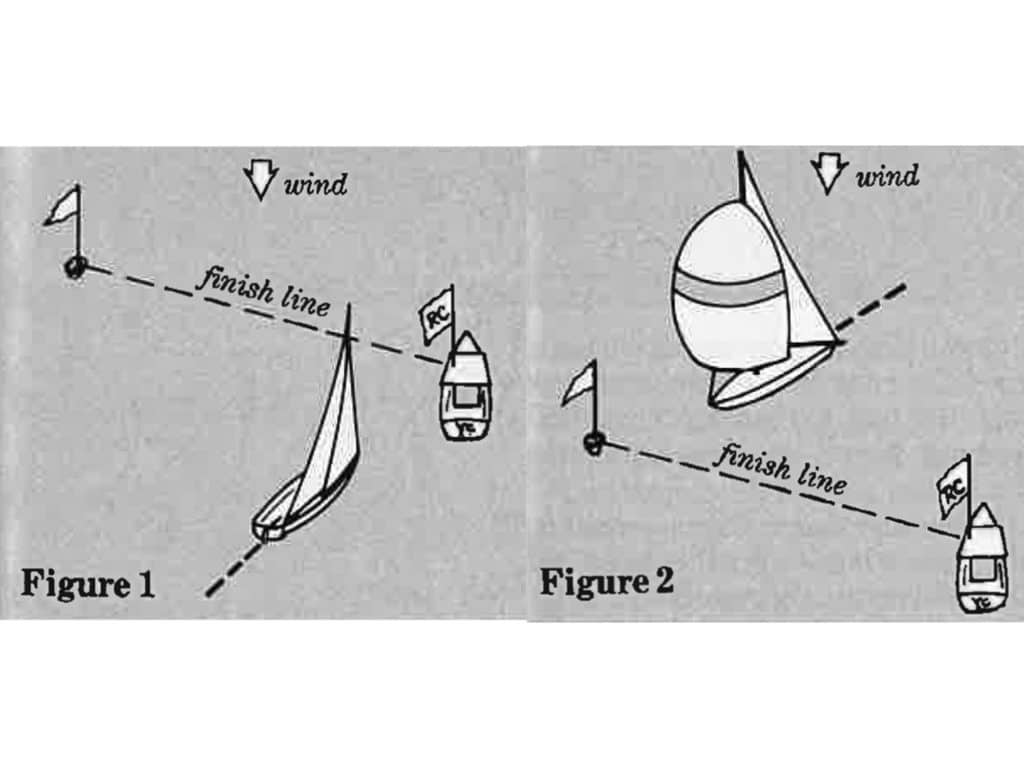

Upwind finishing is very common in one-design racing and is being used more frequently in big boat around-the-buoys races. Because of the wide angles sailed on a beat, finishing to weather offers the most possibilities for gain and, of course, loss. It is a challenge that few have mastered. Strategically, the idea is to finish at the end that is farther downwind (usually the end closest to the leeward mark); you don’t want to sail any farther to windward than you have to (see Figure 1). This sounds fairly easy, but without a chance to check the line to determine the more leeward end, it’s often very difficult to do. It’s particularly hard when the race committee is using a large committee boat and a small mark, since this can cause real perception problems.

Choosing the correct end is a lot easier if you are finishing on the same line that you started on (as is the case on courses that start and finish in the middle of the weather leg). In this situation you know the relationship of the line to the wind and can figure out which end to finish at even before you start (as long as the wind doesn’t change). Basically, you want to finish at the opposite end from the one that was best for starting, which was the upwind end. But just in case an anchor slipped or the breeze shifted slightly, it’s smart to check the line again as you approach the finish.

It’s helpful if you can get an idea of what the line looks like before you get onto the last beat. You may, for example, sail right by the line on the run, or with an Olympic course, you might see the line the second time you round the weather mark. In either case, you should definitely try to figure out which end you’ll go for when you come back up the beat. If the finish line is not set until late in the race, it may be helpful if you can determine which end of the line was set last. That end will likely be downwind and/or down-current from where it should be to form a square line. Of course, unless you’re leading the race, you can always watch where the boats ahead of you finish. Chances are that the leaders, especially the ones that are close to each other, will finish at the best end.

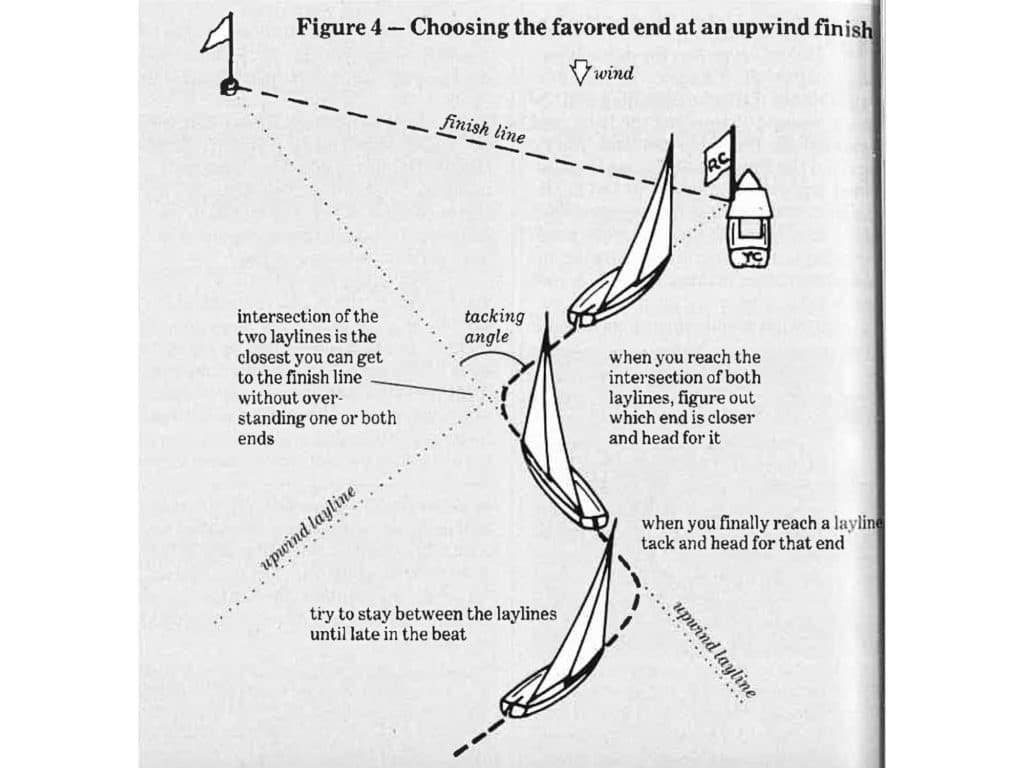

Sometimes you will have no clue about which end is favored as you approach the line. Even if you’ve made a good guess, variations in the wind and the position of each end can change the optimal end instantaneously. What’s needed is a reliable way to determine where to finish as you sail up the last beat. The solution is relatively easy, yet usually forgotten in the complacency or frenzy at the end of a race. Essentially you want to get as close to the finish line as you can (so you can best judge it) without limiting your ability to get to either end as quickly as possible. Do this by staying in the middle of the course as you approach the finish, generally away from (i.e. in between) the laylines to either end; if you end up overstanding what turns out to be the favored end, then you’ve wasted distance.

When you inevitably reach a layline, tack on it toward that end. As you cross the other end’s layline, determine which end is closer and go for it (see Figure 4). It’s that simple! The point where the two laylines intersect is important for a couple of reasons: First, it’s the closest you can get to the line (which makes it easier to judge) without overstanding either end. Second, since you can then sail a close hauled course to either end from this point, it means all you have to do is figure out which end is physically closer to you—and that will be the favored, or downwind, end. When in doubt about where to go, a good rule of thumb is to get on the tack that seems more perpendicular to the line.

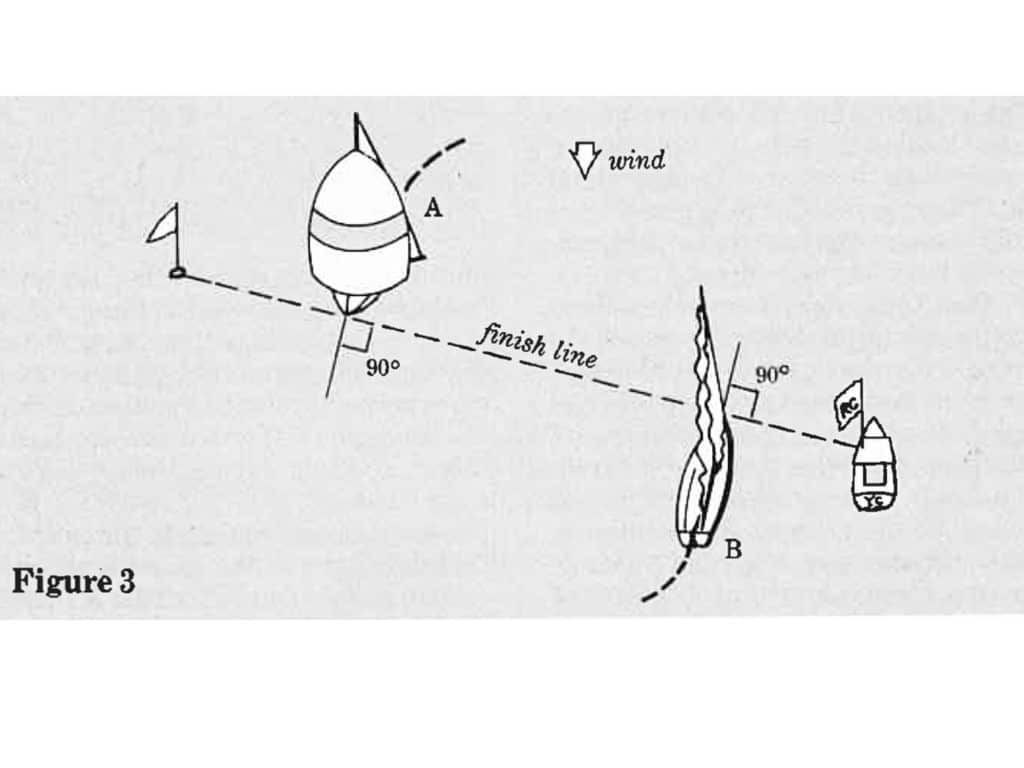

Once you’ve figured out which end is best, go straight for it. Unless there is a big wind shift after you reach the layline intersection, you’ll gain the most by finishing right at the favored end because then you’ve sailed the shortest distance (see Diagram 3). Cross the line as perpendicular to it as possible. If the tack you’re on is already 90 degrees to the line, then keep sailing full speed ahead. If your tack angles to the line, luff before you cross, timing it so that your bow crosses the line before you lose too much speed. Finishing right at an end (instead of the middle) makes it much easier to time this “shoot” exactly right.

RELATED: How to Finish Strong

How far you can shoot depends on how much momentum you have; a light boat like a Laser might shoot only half a boat length, while a heavier keelboat might glide a boat length or more before losing substantial speed, depend on the wind and waves. Personally, I don’t rely too much on momentum to get me a cross the line; I usually wait until I’m half a boat length from the line and then turn the boat so it crosses perpendicularly. In any case, be sure to release the jib or genoa sheet so the sail won’t back and slow you down or force you onto the opposite tack. Of course, you don’t always want to blindly make a beeline for the closer end and forget everything else. If the line is square or if other boats are headed for the favored end too, the most important consideration may be how you position yourself with respect to your competitors. The boat-on-boat tactics of approaching a finish line require a whole separate discussion, but suffice it to say that with a combination of position and finishing at the proper end, you can often beat the boat whose nose was previously ahead of yours.

Finishing on a Run

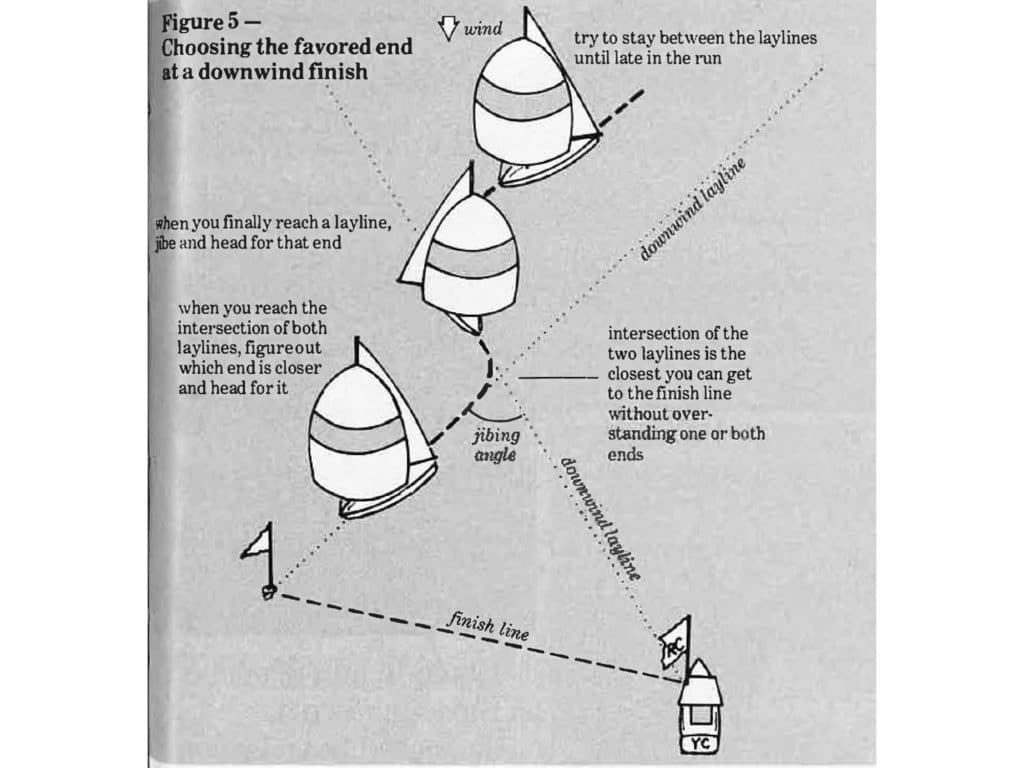

The principles of finishing on a run (defined as a leg where you have to jibe at least once) are very similar to those for upwind legs. The most important objective is to cross the line at the closest point. While the better end on a beat is the one that is most downwind, on a run the favored end is the most upwind one (see Figure 2). Finishing there means you will have sailed the shortest distance possible, if you are finishing downwind on the same line that you started on and assuming the wind has stayed the same. If, however, the finish line was set during the race or there has been a windshift and you’re not sure which end is better, use the same technique you did upwind: get as close as you can to the line (without committing yourself to either end), figure out the closer end, and then head straight for it. Again, stay in the middle of the course as you approach the finish, and when you get to a layline for either end (your optimal jibing angle extended upwind from the mark), jibe on it. When you reach the intersection of the laylines to each end, simply head for the closer one (see Figure 5 below).

Like finishing on a beat, you should cross the line right at the favored end to maximize your gain. This also makes it easier to shoot the line at just the right time, which on a run means bearing away to a course that takes you perpendicular to the line (see Diagram 3). One difference between upwind and downwind finishes is that you can usually shoot the line from a little farther away on a run because there is nothing to slow you down (i.e. heading into the wind). Remember to square back your spinnaker and ease the main as you bear off. Another thing that comes up more often on a run is a buoy room situation as boats crowd the favored end. Each end of the line is a mark, so if you have an inside overlap from the end you’ve chosen, you’re entitled to room to finish there.

Reaching Finishes

Crossing the finish line on a reach seems like it should be the most straightforward of all, but in some ways, it is the most difficult. The idea behind a reaching finish is to head for the end that you’ll get to soonest. Unlike upwind and downwind finishes, however, this is the necessarily end that is physically closer, since you’ll go different speeds depending on which end you’re headed for. In a planing hull, for example, sailing toward the windward end may allow you to plane, so even if the leeward end is a little closer, the speed you gain by planing may be worth a couple of extra boat lengths sailed. With almost any boat, the broader the reach the more speed you’ll gain by sailing higher; what’s required for picking the favored end is a fairly tricky calculation involving which end is closer (and by how much) and how much your speed will vary if you head for one end rather than the other.

Reaching finishes are also tricky because you cannot easily postpone the decision of where to finish. Unlike finishing on a beat or run, there are no layline intersections to wait for; in fact, on a reach, the sooner you’re able to determine the better end, the less distance you’ll have to sail. Unfortunately, there’s not an easy way to tell which end is favored, especially since a reaching finish is almost never on the same line as the start. You just have to get the person with the best depth perception on the boat to figure out which end is closer and then add this into your speed/distance calculation.

Once you get to the line, the same rules apply. Finish at the chosen end, and cross the line perpendicularly. If you start heading for the committee boat end and then suddenly realize the pin end is favored when you’re 50 yards away, it may not pay to head right for the pin. At this point the best way to minimize your losses is usually to sail at 90 degrees to the line and cross it somewhere in the middle. But if you can pick the right end early enough, you’ll get the best advantage by finishing right at that end.

Get in the habit of finishing properly. Give the end of the race as much attention as you give the beginning, and avoid last-leg complacency. Even when your position isn’t threatened as you come up to the finish, practice shooting the line right at the favored end so that when it is close you won’t give up an inch. Finishing at the correct end can shorten the course sailed by large margins and therefore get the race over sooner. And isn’t the whole idea to spend less time on the course than everyone else?