Most contemporary one-designs are based on the principle of all boats coming from a parent set of hull and deck molds, which means the boats we sail today have exactly the same basic deck layout as when they were first built. Class rules usually dictate that the molded shape can’t be altered once the boat is constructed. Yet, hardware placement and rigging systems still evolve, sometimes over decades, and we end up with boats that are easier to sail and almost always faster. One such class is the Etchells, which has been around since the 1960s. From the beginning, it has seen development of ideas and marginal gains in performance, within the class rules. The tinkering nature of the class has often resulted a circular nature of ideas and development, where nothing is really new, but it can pay to revisit ideas long past, as what was tried and discarded years ago may work really well today, especially when done in conjunction with advancements in materials and hardware.

One area of significant development over recent years in the Etchells class has been the narrowing of the jib-sheeting angle. Historically, jib tracks were placed on the side deck, just outside the cuddy (the small raised coach-roof area). This set the sheeting angle at around 10.5 degrees. Over the years, and going back to the origins of the class, various great sailors (including some serious testing by Dennis Conner in the early 1990s) tried narrowing the sheeting angle, with mixed success and uncertainty that such tight angles were actually faster. However, we now know that sailing with narrower jib sheeting angles is quite a weapon, particularly in light to moderate winds and in relatively flat water. Why now and not then? It’s a combination of factors.

First is balance. The trend today is to set the mainsail up with less drag—trimmed flatter and firmer. Secondly, jibs are now being designed with narrower sheeting angles in mind. Notably, they are slightly straighter in the aft sections. In other words, they have “less return.” Thirdly, boats are now stiffer, as are masts, giving more control over headstay tension and thus jib shape.

Two recent performance gains have been the domination by Peter Duncan’s team (which included Jud Smith) in the Etchells Miami Winter series of 2013-’14 and the domination of the 2019 Etchells World Championship in Texas, the winning team led by the talented Iain Murray. Duncan’s team fitted a jib track to the top of their boat’s cuddy, set at approximately 8.5 degrees. That winter series saw many race days in 10-knots of true windspeed, or “full-power” conditions. The two Australian teams had a block-and-tackle inhauler system and were regularly sheeting to 7.5 degrees, complemented with a very firm and flat mainsail, and the traveler set relatively high.

Having always been drawn to deck-layout solutions, I started experimenting with how best to sheet an Etchells jib narrower. One challenge was that the class rules do not allow altering the molded surface, which includes the cuddy. So simply chopping part of the cuddy away (as seen on all sorts of grand-prix race boats) isn’t an option. Another factor is that nobody wants to freely give away sail area. So, in order to sheet the jib properly on top of the cuddy, raising the jib clew would be the last option to consider.

Initially, in 2014, we employed a deflection system, whereby a strop was connected to the jib sheets, dragging the sheets toward the boats’ centerline. Simple, but effective. However, as the angles got narrower, there was too much friction for this solution to be practical.

In 2018, we simply placed thru-deck bushes where we thought the narrowest sheeting angle would be (8 degrees) and had a simple low-friction ring connected to a below-deck purchase to control the up-down lead angle. This was great when in favorable narrow-sheeting conditions, but as the breeze built and sea-state increased, it is faster to be out to the traditional, or wider, sheeting angle. So, we installed another similar system at approximately 11 degrees, allowing us to sheet to the widest angle in 20-plus knots of true-wind speed. But in medium winds, we needed to sheet between the two extremes, which put a massive load on the system, as we were triangulating between the inhaul and outhaul system in order to get the jib lead down to the cuddy top.

Apart from the loads and friction, this system required a highly skilled jib trimmer and risked a brief performance loss if controls were not managed accurately. For instance, if you wanted to mode the boat faster, meaning you needed to widen the main’s and the jib’s angle of attack, the trimmer had to ease the inboard control before pulling the outboard control. This resulted in the jib lead rising, in turn causing the jib to lose its shape and twist profile, and the boat fell out of balance. Every time you made a change, you had to accept an initial performance loss.

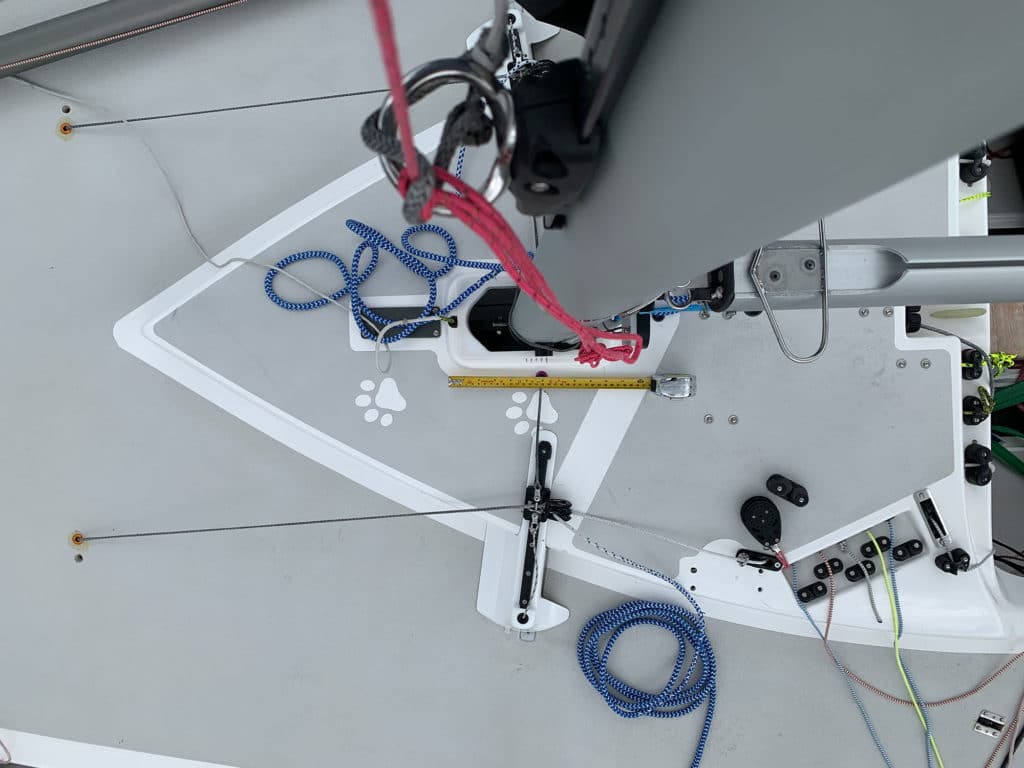

During the winter series of 2019-’20, with the limitations of the double-bush system in mind, I fitted an athwartships track and car system on the cuddy top and bridged it out onto the side-deck. The idea was to maintain the ability to sheet wide in fresh conditions. This system immediately revealed several advantages, most notably the ability to achieve consistency in sheeting angle and vertical lead height. It gave us simple and accurate jib trimming, which meant less experienced jib trimmers could accurately work the system and, of course, it allowed eyes and minds to remain outside of the boat. Only two problems remained: The assembly looked appropriate for a tractor than on a sleek Etchells deck. Also, more geometric testing needed to be done to prevent jib camber and twist from changing across the entire length of the track.

The best way to place an athwartships jib track is for it to be radially equidistant from both the tack and the head of the jib, but given the Etchells’ cuddy profile, and the need for the outboard end of the track to extend out over the cuddy edge to the side deck, the same measurement from the head of the jib to the outboard end of the track would mean the outboard end of the track would be 6.5 inches above the deck! Clearly this would not pass aesthetic muster. Plus, it would be a major trip hazard for the foredeck crew and have significant windage implications.

I therefore placed the track aesthetically and equal-distant to the forestay only. I then collaborated with the UK Etchells builder David Heritage to custom-make a mounting for the outboard end of the track that would not detract too much from the traditional look of the boat. Over several weeks we tried three variations, finally settling on a shape that blended in well with the deck. It was also structurally reliable and simple for owners to retrofit. Whether we achieved a decent aesthetic result is in the eye of the beholder, but knowing the advantages it offers, I am OK with it. We customized a Harken car to get the jib lead height as low as possible to the deck, discarding the bale supplied, and rounding the hard corners of the car to prevent our highly loaded up-down strop from chafing and breaking.

Next came the geometry, knowing we had given away the equidistant measurement to the head of the jib for the sake of styling, windage and safety. As a result, the distance from the outboard end of the track to the head of the jib is about three inches longer than to the inboard end of the track. This would result in the jib leech rapidly tightening for every move outboard. The ideal solution lay in the athwartships position of the jib lead’s up-down control—which was positioned forward—and the lateral location of the jib-sheet control blocks on the aft side of the track. Essentially, the placement of hardware needed to “give back” some (but not all) of the vertical difference on the jib track. I say “not all” because, as the lead rises, the force of the jib sheet also pushes it aft, just like moving the car aft on a traditional fore-aft track.

This could only be resolved by testing. So when UK COVID restrictions were eased in May, allowing us back on the water, I was out there with friends, honing in on the correct hardware positions. I’d love to report that I nailed it first time. Close, but it took a few holes in the deck, fine-tuning of control systems and hours sailing to achieve the “same camber and twist for the length of the track” goal. The best outcome of the new system is making it easier for any level of crew to achieve consistency in jib trimming at tighter sheeting angles and a higher level of performance in a class that has been around for more than a half century.