We were in a bad position off the start. The wind unexpectedly shifted in the wrong direction, and we were immediately at the back of the fleet. I could sense anger building in my head, and I was struggling with how to deal with the “unfair” bad break we’d been handed. The leading boats all looked to be well ahead, and it appeared that there would be no coming back. I went dark.

One of the crew saw my emotional state, came aft, and said to me, “If anyone can get us out of this, it is you.”

Really? I thought.

At that moment, my sour mood shifted, and I asked myself, How can we recover?

Snapped out of my misery, I went to work. Over the next four legs of the windward-leeward racecourse, we connected one favorable windshift after another, and focused on staying in stronger wind while the leaders inevitably missed a few shifts while tacking on one another. At the final leeward mark, we had sailed from last up to second place in the eight-boat 12-Metre fleet, and as luck would have it, the leader overstood the finish line, and we won the race.

Overcoming an emotional setback is difficult, but recognizing in the moment what we can and cannot control is essential to influencing the outcome. I was reminded of this recently during a late-autumn daysail in Annapolis, Maryland. The afternoon sun was fading, and I found myself racing to get to the Spa Creek drawbridge before it closed for the afternoon rush hour between 4:30 and 6:00. The same helpful crewmate from my earlier 12-Metre experience happened to be on board with me. My watch read 4:03. We had 27 minutes to reach the bridge for the final opening, and yet we were 3 miles away, with the wind slowly fading. Making matters worse, my electric motor wasn’t working.

I must have displayed the same negative emotion I had during that 12-Metre race because my crewmate squared his shoulders and said, “I bet you will find a way to make the bridge.”

The pressure was on to make it through on time. It was another challenge, and once again, I went to work. I asked him to sit to leeward to induce heel. I adjusted the sail controls for light wind. I studied the water and took advantage of every puff and windshift. With 7 minutes to go, we were still a third of a mile away. Just when we needed it, a miracle gust accelerated us toward the bridge, and I called the tender as we neared. The bridge deck opened at exactly 4:30, and we sailed right through.

These two moments reinforced the notion that we can overcome emotional setbacks and gain confidence, but in order to do so, we have to first recognize that the emotion is real and to transform negativity into a challenge that can be overcome.

Overcoming negative emotions is difficult in every sport, including sailing. Coaches, weather experts, and tuning gurus are helpful with the technical aspects of sailing, but in recent years, high-level sailors have turned to sports psychologists to help hone the mental part of the game and build confidence. Dr. Tim Herzog, an Annapolis-based sports psychologist, method performance coach and founder of Reaching Ahead, is one who has worked with top-level sailors. I recently sought him out to learn how he instills confidence and clarity in those who seek his help.

“Training your brain should be no different than training your body,” he advises me. “Everyone will tell you that the mental part of the game is the most important. Some sports cultures perpetuate an attitude that one must take care of the mental part of the game by oneself. Yet, at the top levels of sport, we would not expect anyone to go without a strength and conditioning coach. Brain training is no different.”

We can’t control our initial thoughts when something goes wrong on the racecourse, Herzog says. It’s natural to become upset or emotional, but our next thoughts are important. “Center your thoughts on things that you can control,” he advises. “Accept your emotion. If you try to squash it, then it can get worse. Bring your thoughts to things that are controllable.”

My technique is to do two things: First, I say aloud, “OK, let’s have fun working out of this bad spot.” Using the word “fun” reminds me to put things in perspective—it’s only a sailboat race, and it’s supposed to be enjoyable. The second thing is to switch focus and try to sail the boat “by the numbers.” I try to be more pragmatic and think about how to make deliberate moves. Patience is an asset when we are behind because it’s rare to pass an entire fleet in one bold move.

We can’t control our initial thoughts when something goes wrong on the racecourse. It’s natural to become upset or emotional, but our next thoughts are important.

Paul Cayard, one of America’s greatest racing sailors, once said, “It’s amazing how boats will get out of your way if you just stick to your game plan.”

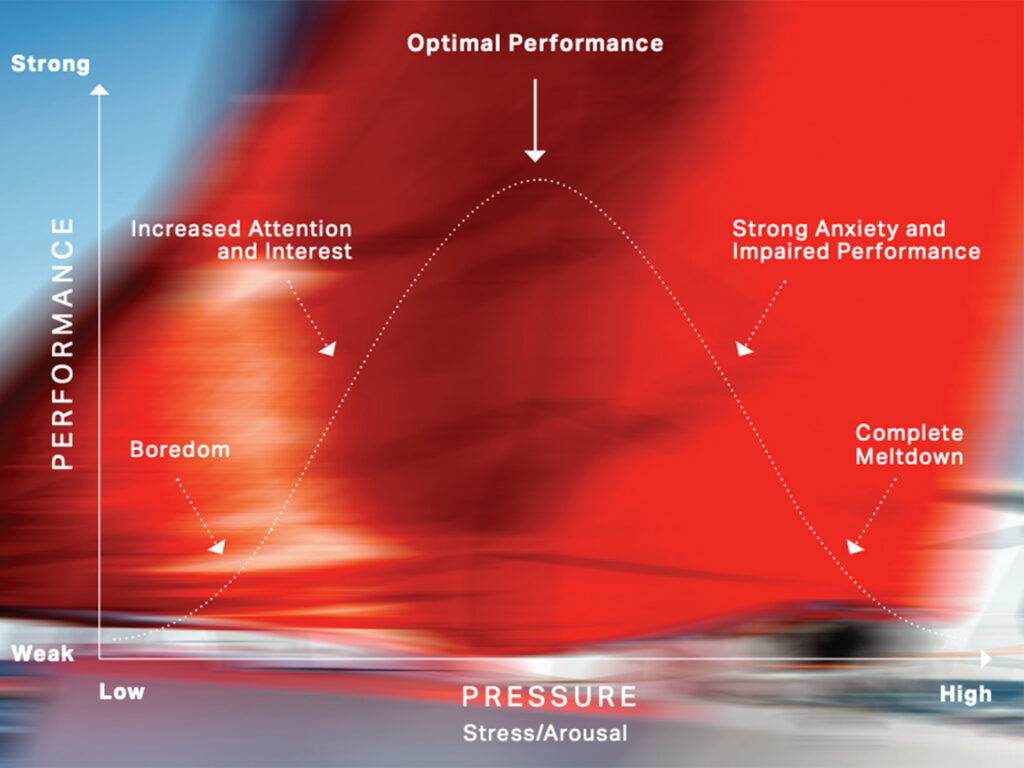

He’s right, and to drive home this point, Herzog refers me to a diagram (opposite) he uses to illustrate things a sailor can control. He uses an acronym: USODA (which he points out does not stand for the United States Optimist Dinghy Association). He starts with an inverted “U” that is a graph plotted on an X-Y grid, with “performance” on one axis and “amped” on the other. The graph shows that we need to be “somewhat amped” to get the best performance, but if we get too amped, our performance will fall. The “S” is for “speed,” or how we set and tune our boat. The “O” is for “offense,” which he defines as “big-picture strategy.” The “D” is for “defense,” or short-term tactical decisions. And the “A” is for “agility,” which includes crisp maneuvers, being smooth on the boat, and steering well.

“If something goes wrong, replay it one time,” he suggests. “Don’t be hyperfocused on something negative. Instead, replay five times something that you want to do correctly. Bring your thoughts to the controllable. Little voices can be distracting.”

When asked how we build a desire to excel, Herzog says: “Readiness is important. Mental preparation is a big part of the game. Shift your attention away from the outcome and toward the process of the race. When you feel anxious, sad or angry, just accept the emotions, and then let them go. Again, work on the controllable things.”

I have found that thinking back to past successes has helped me overcome emotions at times. For lectures, I use fun stories about races that went exceptionally well, and a few races that went exceptionally bad but are good tales. The overall message is to use examples of victory and defeat to emphasize that comebacks are possible and disappointments are inevitable, but confidence is a contributing factor in either outcome.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary definition of confidence is: “A feeling or consciousness of one’s powers or of reliance on one’s circumstances. Faith or belief that one will act in a right, proper, or effective way.” Gaining confidence is an essential ingredient in achieving success.

It is easy, however, to be overconfident—a trap that has ensnared many sailors. We want to feel confident that we have carefully prepared for a race, but as all sailors are aware, there are factors we can’t control—weather, windshifts, the actions of others, equipment breakdowns, rushed decisions, and any number of unplanned mistakes and mishaps.

Take time after every race to debrief with the entire crew, and with yourself if singlehanding (a miniature waterproof notepad should be in every sailor’s pocket), and outline what went well and what can be done to improve. Make a list and write things down in a logbook when back ashore. When you review past mistakes, it will help you to avoid repeating them.

The best sailors embrace the attitude of improving with every race. Regattas are won by sailors who consistently sail with the best average. They rarely make risky moves because being steady pays in the long run. Prepare in advance by making sure that every piece of equipment is in good shape, the correct sails are selected, the afterguard understands the weather forecast, there is tactical knowledge about what the competition will likely do, that everyone is familiar with the Sailing Instructions and, most important, the crew is sure that everyone on the boat is ready to do their job.

If these pieces are in place, your crew will have the confidence that you will have a good race. When you find yourself at the back of the fleet like I was, that confidence can help you move to a better place on the amped axis, and what do you know? Your position on the performance curve, and in the fleet, will advance as well.