Halyard Locks

It wasn’t long ago that every sail change involving a spinnaker (hoist, takedown, or peel) on a large ocean racer involved sending someone on a harrowing journey up the rig. The problem was, the stretch and chafe created by flying a spinnaker for days could eventually eat through a halyard. The solution was to lock the spinnaker to a short strop at the top of the mast, allowing it to carry the load. It saved halyards, but it was dangerous, and made bowmen miserable. There had to be a safer, faster alternative.

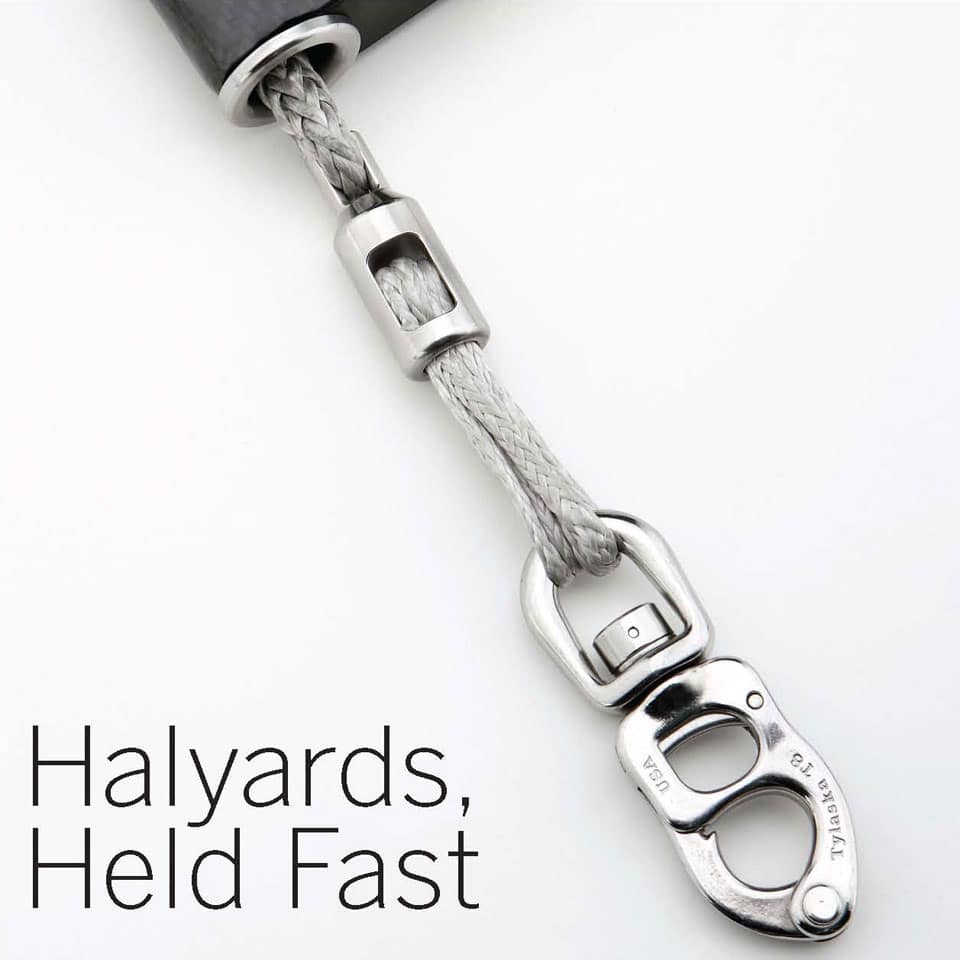

Enter the halyard lock (see the photo gallery here): a mechanical fitting that bears the brunt of a loaded halyard, thereby eliminating the effects of halyard stretch, as well as long-term halyard fatigue and chafe. It can be quickly released from on deck, eliminating the need to send the bowman skyward. With several manufacturers now offering refined, albeit incredibly expensive, systems, lock applications are slowly expanding beyond the top of the grand-prix pyramid, and trickling down to the recreational grand-prix arena.

In concept, the halyard lock is relatively simple: As a halyard is pulled up to full hoist and through the lock, a “bullet” spliced directly into the halyard triggers the lock to close, seizing the bullet. To release the lock, the halyard is pulled up again, thereby releasing the captive element and opening the lock, allowing the halyard to run.

Mainsail halyard locks may be integrated into the headboard car of the sail itself, with spring-loaded levers dropping into specific slots in the mast (i.e., full hoist and reef points).

Some halyard locks for mainsails and headsails (as well as the original Strop Locks developed by Southern Spars in 2004) rely on trip-lines to disengage the locks. The latest units from Hall Spars do not require trip lines.

“About five years ago I watched the guys on some of the maxi boats lock a halyard on a mainsail with a trip line and then send a guy up the rig just to make sure it was locked,” says Eric Hall, of Hall Spars and Rigging in Bristol, R.I., which now offers an extensive line of what it calls AutoLocks. “I thought to myself that there had to be a better way.”

Hall’s solution was to automate the locking mechanism. Here’s how it basically works: when the metal “bullet” passes through the device as the sail reaches full hoist, the bullet triggers a set of flaps, which open to hold the bullet captive. To release it, the sail is hoisted a few millimeters, the flaps disengage, and it’s unlocked.

Hall AutoLocks, Southern Spars Strop Locks, and units from Karver and Facnor (the later two being more commonly found on furling headsails on maxis) can be used externally, attached by a strop, or built into the mast. Eric Hall says that as they continue to improve their own offerings they’re considering many more applications. “You could use one any place you want to stop something from moving instead of a winch or a cleat,” he says.

Locks, for example, can also be used in-boom for reefing systems. PUMA Ocean Racing’s mar mostro is set up with this system, and skipper Ken Read says this application alone is one of the best developments to come to the Volvo 70 fleet. As with a halyard, take up the reef line, the bullet enters the lock and engages it. To shake the reef, pull the reef line again to unlock it, and let it run.

As ideal as the applications may sound, Hall admits the locks are not perfect—yet.

It’s easy to lock them when the sail is hoisted, he says, but when you go to take it down, when the halyard is under extreme loads, especially on bigger boats, as you pull the halyard up to take it off lock, you don’t know if you’re just stretching the halyard or whether the unit is simply not working. “You have to somehow know that the triggers are moving,” he says. “Moving the halyard a few millimeters to trip the lock can be tough. You just don’t know when you’re beating the inherent stretch of the halyard.”

For buoy racing, they can be more of hindrance than a help, says professional rigger Brian Fisher, of Rig Pro: “Many of the TP52s don’t use them—with the exception of the coastal races—because the whole sequence of getting off the lock can be complicated.”

The solution Hall is currently working on is a system that uses a miniature magnetic proximity sensor, integrated into the lock unit, to transmit a signal to a deck display, showing whether the unit is in locked or unlocked status.

But of the benefits, Hall thinks primarily of performance and repeatability with settings. With the halyard always set to a fixed-hoist point, luff-tension adjustments can be made with jib-cunningham systems; hydraulic or otherwise. And making a case for further harnessing the wind’s power, says Hall, consider that, as a spinnaker pumps, the halyard stretches, and, in theory, the rope is absorbing the energy, not the boat. “If the halyard is locked, that energy pushes the boat,” says Hall.

There’s also the important issue of preventing halyard chafe; the sawing effect of highly-loaded halyard over a sheave or other turning point can be a major headache over many ocean miles: with locks, at least, there’s no need to regularly change the halyard position.

The lock unit itself has been a challenge to get right, Hall admits. The company is on version five (and 2 to 3 years with the current concept), but they’re happy with the reliability. In terms of maintenance, a lock is like a winch: if you leave it exposed over the offseason it will need to be cleaned and lubricated before use, and even if it’s regularly used, one will eventually need to be lightly serviced.

While the cost of the units (Hall’s smallest 2-ton external unit costs $4,600), has kept widespread use in check, the most significant hang-up for would-be customers is that daunting potential for it not to unlock when a sail needs to come down. Getting the bullet placement right was a problem of the past, one that they’ve worked to eliminate. “Initially, we caused our own problems by not educating the riggers early on about how to splice the bullets,” says Hall, “but we’ve figured that out and it’s no longer an issue.”

One common notion about halyard locks is they reduce compression on the mast, thereby allowing for a lighter mast, and also the possible use of smaller diameter halyards, yet another weight savings. “On big-boat masts compression is not an issue at all,” says Hall. “Maybe with a masthead spinnaker on a fractional rig it might help.”

And when it comes to looking to locks as a means of downsizing halyards, Hall also cautions against this idea: “The limit is the weight of the sail,” he explains. “Sure . . . you could pull it up with string, but we encourage the use of regular-sized halyards so you don’t have to worry if the lock stops working—you could still hoist and rely on the halyard. Also, a lot of time; on a long leg you may take the sail off the lock early, in time to douse, so you would need that halyard to hold the load.”