Once upon a time, the Martin 242 Class lived in its own bubble and had everything it needed: a builder of keels (MG Marine in Los Angeles), rudders, masts, booms, and spinnaker poles; multiple sailmakers; all kinds of spare parts from hardware manufacturers; and enough of a footprint on the West Coast of North America (about 125 boats, plus more boats in other Midwest and East Coast locations) to keep everything humming along year after year.

But then one day, about three and a half years ago, it became apparent that there were only four anodized mast tube extrusions left in the hands of the builder, who was not going to be able to make any more in California. Plus, the mast assembler—Buzz Ballenger, of Ballenger Spars—was retiring and didn’t want to finish any more extruded tubes after the last four were dealt with. At this point, three of them were snapped up, turned into finished masts, and shipped to buyers. The fourth tube was set aside by the builder for test use by a future mast assembler.

As such, the class faced a slow-burning existential crisis, because without a supply of new masts it was basically doomed to a slow death: we collectively usually broke about two to three masts per year on average.

The Martin 242 is a lighter-air design and construction grade (for 8-12 knots of breeze) and was originally intended in the early 1980s as a small racer-cruiser for couples and young families. For the past 20 years it is used almost solely for hard-core racing in all wind conditions, and as such the masts are pushed beyond their intended envelopes. Top teams compete in anywhere between 80 and 130 individual races per year, and the boats and masts are wearing out faster than perhaps intended. With this in mind, in 2021 the M242 Class Technical Committee put together a “M242 Boat Maintenance Handbook” to show owners how they could stiffen or repair known weak points on their boats.

In mid-2021, I undertook an inventory of used and broken masts up and down the coast and it was clear that there were perhaps only eight or nine useable old masts (plus two more that were seriously degraded) that could be brought back into service or spliced together, if required, after which we would start losing boats as masts slowly broke each year.

Launch of the Mast and Boom Project

As a result of seeing what was happening years ago and making a series of inquiries, I started the Mast and Boom Project in mid-2021 for the Regional Fleets to see what it was going to take for the class itself to build its own masts, booms, and to a lesser extent, spinnaker poles.

I quickly turned to Stewart Jones, Founder and CEO of Pro-Tech Yacht Services in North Vancouver, and made a handshake deal in late June, 2021, that if I could find an extruder somewhere in North America, Pro-Tech would receive the bare tubes and assemble the masts, which also involves the complex process of cutting and tapering the upper 8 feet of a tube and welding on a mast crane that the backstay attaches to, much like a Melges 24 or J/70.

Jones also built a spinnaker pole for us which we placed into Fleet One’s inventory, so that took care of a relatively minor, but important, item on a go-forward basis. Mike and Denise George, of MG Marine, were amenable to this solution, and thus we were off to the races, so to speak.

Well, that’s where the fun began. Do you know how hard it is to find an extruder in North America that a) wants to extrude mast tubes, and b) is willing to embark on getting a custom die built, and c) is willing to work with tiny volumes like 1,000 kilograms for 40 masts? It’s like searching for a needle in a haystack. The good old days of omnipresent mast extruders are long gone.

Over the next two years I contacted numerous extruders throughout North America and also a number of one-design classes to see who they used (Lightnings, J/24, Etchells, Stars, Cal 20s, etc.) plus the websites for Fireballs, 505s, Melges 24s, J/70s, etc., and the results could be grouped into a few common categories:

1. “We get our masts made in (Australia, England, France, etc.)” which would have blown our budget to pieces due to shipping costs and flying back and forth for quality assurance. And two classes use carbon fiber masts (Melges 24 and J/70) which the M242 class does not allow.

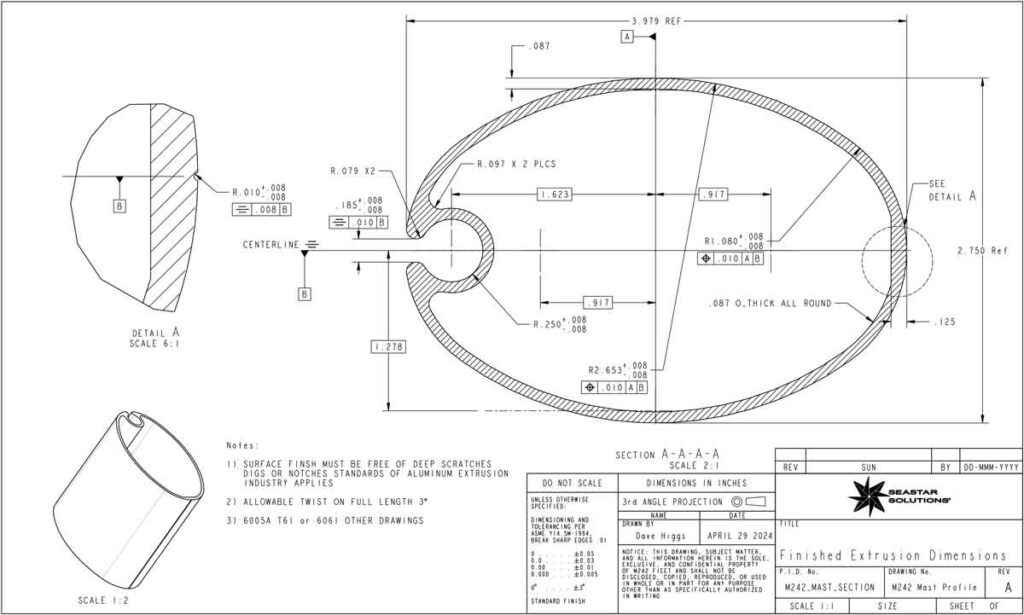

2. “We can make some mast tubes for you in the volumes you are looking for as long as you select one of our existing designs.” This would have all been a radical departure from our current mast design and basically created a new sub-class of Martin 242s that used those spars (see the inserted diagram of our standard cross-section). Incidentally, the Cal 20 Class cross-section (“Size #3”) from the Zephyr Division of Cape Cod Shipbuilding was close to ours in terms of being the same dimensions front-to-back, but an eighth of an inch narrower side-to-side with a slightly thicker wall. The supplier, however, had only made them in 33-foot lengths (and net-new orders were only going to be 30 feet), which would have posed a splicing requirement as well, plus high shipping costs from the East Coast, plus quality assurance travel costs. Paradoxically, we had to entertain the splicing solution anyway when we found our eventual extruder.

3. “We can make some mast tubes for you as long as you order 250,000 pounds of aluminum per year minimum.” That one was my favorite response. I basically laughed when the sales agent mentioned that number, envisioning a veritable mountain of masts at huge cost that would last for centuries. At least one other extruder also had a much larger minimum-order quantity than we were offering.

4. “We are interested in extruding tubes for you – can you send us your diagram and some other details?” After a bit of back-and-forth regarding details, I never hear from the outfit again. That was a common occurrence. And one East Coast mast-building outfit was slammed with work and could not take us on.

And then there was the conversation with the prior extruder in California who was able to find our die in their database and said, “We shredded that one about two years ago because we hadn’t gotten an order within our required timeframe,” at which point my head exploded. And then their engineering department refused to build an identical die to be able to punch out a few tubes for us, even though they had the diagram on file. Alas.

Incidentally, during this exploration process I had a couple of very helpful conversations with Tom Allen, builder of Lightnings, Highlanders, Blue Jays, and Jet 14s in Buffalo, New York. Allen said he had recently concluded a two-year search for a new Lightning mast extruder in the Midwest, and that he was satisfied with their quality. And yes, I tried that extruder also but they did not respond to my inquiries: they may have been too busy or our order volume was just too small.

At this point (almost two years in) I was discouraged and reported as such to my colleagues on the M242 Class Technical Committee, but I was resolved to keep at it due to the existential nature of the issue. Incidentally, the related, yet secondary, search process for an anodizing facility was also proving to be challenging, but the assumption was that an extruder would have access to an anodizer, so it would hopefully be a package deal.

Then, one day in Vancouver I was kvetching to my sailing buddy Derek Gauger, an engineer, about how hard it was to find an extruder, and Derek said, “OK, let’s fire up the laptop and see what the heck is out there and maybe we’ll get lucky.”

Lo and behold, on the first hit Gauger found a Google listing for a new state-of-the-art aluminum extrusion facility in Langley, BC (Apex Aluminum Extrusions), that was 30 miles down the road from where we were sitting. Google must have noted our location (and desperation) and done its usual brilliant job of pairing up need with supply. After I recovered from the surprise, I contacted Apex’s senior account executive at the end of March, 2023, and he expressed an interest in extruding tubes for our class, and shortly thereafter his sales estimator provided a quote.

Well, that’s where the fun began, Round 2.

So Much More Than A Tube

I’ve learned more in the past year and a half than I ever really wanted to know about tolerances, floating holes, minimum wall thicknesses, acceptable twist, mill finishes, splicing, anodizing, tapering, welding, painting anodized aluminum, shipping, long-term storage requirements for dozens of anodized, non-anodized, or painted tubes, the limitations of CAD, etc. Oh, for the good old days of just calling up the builder and saying, “I’d like a new mast in a month, please.”

Why is it so complicated today? Well, what we are trying to do is unique for a class: We have very limited experience and are essentially going into business for ourselves to raise money to build a relatively small number of masts and booms, which is no less complicated than a large number of both, whereby we are subcontracting the die creation, the extrusion process, the anodizing and the final mast and boom assembly. Plus, we’re making all the technical decisions around the die design and the aluminum material being used, which are both fractionally different from the prior design due to Apex’s in-house manufacturing constraints. It’s very, very complicated with lots of interconnected parts and timelines.

We also had one of our Martin 242 engineers (Dave Higgs) recreate the CAD diagram of the paper-based die design from the prior extruder and fine-tune it working with Apex. It was a blessing that Higgs has vast experience with extruding and anodizing millions of pounds of many different aluminum items during his career and has worked with many different companies to create extrusion dies, so his involvement for the past year was invaluable. And it turned out that his chief design counterpart at Apex was someone he’d worked with before at another company, so that sped things up a lot in the past three months because they both spoke the same technical language.

The Die Has Been Cast

So, here we are in late 2024, and we’ve been informed by Apex that the die has been received, and they will shortly punch out the first two 12-inch test sections with a mill finish for us to inspect, after which we’ll get those little sections clear-anodized at a facility in Port Moody, BC, that Pro-Tech uses all the time. One will get shipped to our California Technical Group for their review, and the other will make its way around BC and Washington State. The cost up to this point is about CDN$5000 ($3,600).

Assuming everyone on the Technical Committee likes what they see, the next stage in February, 2025, most likely, is to punch out 200 feet of test tubing and have it cut into nine or so 20’3” sections so that we can build two test masts from four of the tubes and perhaps sell the rest to M242 boat owners who want a deal on bare unfinished tubes. The cost for this component is another CDN$1,400 for the tubes ($1,000) plus perhaps CDN$5000 ($3,600) for the two mast builds. Shipping from Apex to Pro-Tech is included in the pricing, so that is a major bonus.

A 242 mast is normally 36’9” long, and when built in California these long tubes were able to be anodized in large tanks, but Apex’s in-house tanks are only 28’ long, with an effective length of 27’6” due to 1” wide anodizing tank support rack marks being burned onto the tubes 1.5” from each end (see: I told you it was complicated…)

The Technical Committee debated a number of assembly options and finally settled on splicing two tube sections together about 6 inches below the spreaders, and each tube would yield an 18-inch inner sleeve section for the splice below the spreader level and also the boom vang. At least the 18-inch internal sleeve material can have burn marks on it, so that way we don’t waste the material at one end of the big tube. “When in Rome” and “beggars can’t be choosers” were used on at least one Technical Committee group call.

Putting Rigs Into the Field

Assuming the test masts hold together over a summer of racing (candidate boats are being solicited now), we will place the final order in September or October 2025 for about 80 additional tubes, which would be immediately anodized by Apex for long-term storage. Pro-Tech may be able to store 25 tubes, and the Royal Vancouver YC may be able to handle 20 or so in its Dry Dock building in the rafters, but the plan is to sell bare tubes at low cost to as many M242 owners as possible to have them store the tubes in their basements, garages, businesses, or wherever, and pull them out when they want Pro-Tech to turn the unfinished tubes into useable masts or booms. We will get it all figured out. The cost for this component is another CDN$13,000 for the tubes ($9,300) plus perhaps CDN$2,000 ($1,400) for storage racks (if needed).

We are confident we can self-fund this entire project as a class, and some individuals have already stepped up with loans and advance payments, and in the coming months as we ramp up the marketing campaign we have no doubt others will assist as well. And three of the fleets have already chipped in substantial funds. The project financials are all in the public domain, and can be seen as a sub-link lower down in the Mast Project tab of the Fleet 1 & 2 website at m242fleetone.org

The basic concept going forward is that the Class will sell bare tubes out of inventory over the coming years (and perhaps decades) to Pro-Tech, who will be responsible for all the mast and boom build aspects, plus dealing with the end-buyers and collecting the money. They will also have control over the end-pricing for the masts. M242 owners who have pre-bought their own tubes would of course get a discounted build price from Pro-Tech, so there’s a fair amount of incentive for boat owners to pre-buy tubes, especially if they have original 40 or 45-year-old spars that are on their last legs.

Wish us luck, because at this point there is no Plan B, but we assume Australia, New Zealand, or Europe would be the future fallback plan for lining up extruders.

Michael Clements, Martin 242 Fleet One (Vancouver, Canada) Executive Committee Member, is a four-time Martin 242 North American Champion