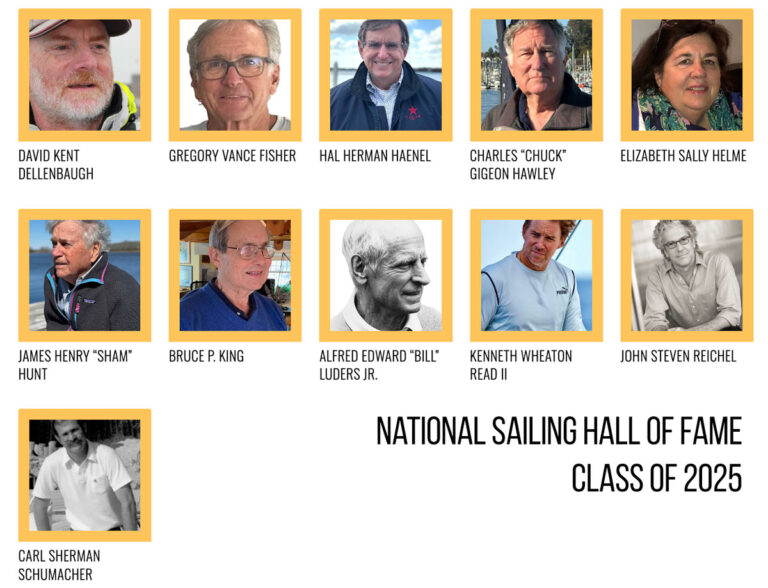

Hurricane Sandy and Moondust

Thanks to Sandy, I have now nursed sailboats through two hurricanes (or hurricanes that were fading into the tropical storm category, if I am totally honest). One sailboat, a Bristol 35.5, was at sea, and we ran into Hurricane Mitch in 1998, after the storm surprised everyone by doubling back east and running over the southbound Caribbean 1500 fleet. And the other, my new-old Beneteau 36.7, Moondust, was sitting at a pier on the Rhode River on the Chesapeake Bay when Sandy roared through this week.

The big difference between protecting a sailboat from a hurricane at sea, versus at a pier, is, of course, that when you are at sea your own safety and life (along with your crews’) are in play as well. That is about as high stakes as any game gets. So Hurricane Mitch was a stressful series of days: trying to anticipate where Mitch would track and how to stay away from the worst of it, and then enduring the actual wind and waves (we hove-to for about 12 hours). One of my crew experienced something like PTSD and sat out of the watch rotation for a few days after, recuperating. After we finally made it safely to Virgin Gorda, I remember that it took a few weeks of Planters Punches and Caribbean relaxation before the knot in my stomach completely dissolved.

But the big similarity is that dealing with a hurricane requires a lot of planning, forethought, and trade-offs. And this may sound weird, but it is a challenge (me vs. the power and unpredictability of Mother Nature) that I actually enjoy. You are making complex and subjective decisions under pressure, with real consequences. That puts you deep into the moment and yanks you clear of all the normal life BS, which is easy to believe is important absent major hurricanes.

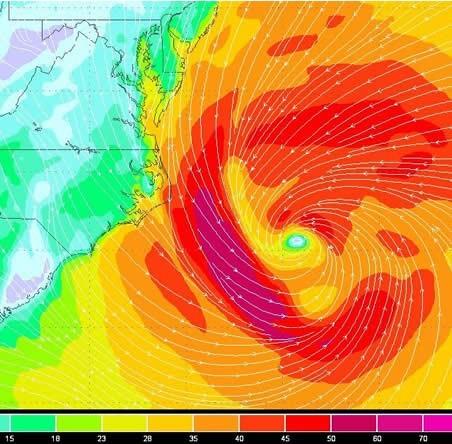

Sandy makes her approach to the mid-Atlantic.

When it comes to the Chesapeake Bay and hurricanes, the biggest question is whether the eye will pass to the east or to the west. The east will mostly produce northerlies, which tend to push water out of the Bay, minimizing storm surge (and also helping negate any flooding from rain). You are dealing with a wind event.

In contrast, if the eye passes to the west, you are in the danger zone that will be dealt southerly winds (that have the added turbo-boost of the speed by which the storm is advancing), which pile an enormous volume of water up into the Bay. You are facing a major wind event, PLUS a serious storm surge danger. In 2003, Hurricane Isabel made landfall on North Carolina’s Outer Banks and ran inland and to the west of the Chesapeake. That track put a lot of Annapolis underwater, and the high water wrecked both marinas and yachts.

Sandy was a fickle, indecisive storm. A few days out, there was little agreement between weather models on where she would make landfall. The southernmost model tracks had her coming up the Chesapeake Bay, and landing a direct hit (high winds plus storm surge) on Moondust. A pier offers iffy security with a 5-8 foot rise in water. Not only do you have to keep adjusting lines and think about wave action, but my pier in particular is not all that solid (plus, there is another sailboat that lies against it). If the entire thing was underwater, I could easily imagine it floating free of the soupy Chesapeake bottom. So I was thinking that I might have to go anchor Moondust around the corner in Whitemarsh Creek, which has 360 degrees protection. Of course, anchoring out then puts you at the mercy of your ground tackle, and there is always the danger of other boats around you coming free and smashing into your well-secured vessel. And do you stay with the boat—which is best to maximize the boat’s chances but also puts your own safety back in play—or throw out whatever anchors you have and come back after it’s all over, with your fingers crossed?

Happily, the computer models started to come to agreement, and push Sandy’s track north, as she approached the coast. Leaving Moondust on the dock seemed a viable and reasonable plan. To confirm my thinking, I called Alex Schlegel, who runs Hartge Yacht Yard in nearby Galesville. Alex has lived his whole life on the Bay, and his instincts about what wind and weather will do on his home waters are second to none. I asked Alex whether he was recommending to sailboat owners with slips at his yard that they haul for the storm. “I don’t really know why people haul their boats for hurricanes. They end up getting blown off the stands,” he replied. “The worst that can happen in a slip is that you rub against the pilings.”

I guess Alex has much more confidence in his pilings and piers than I do in mine. But, as usual, he made practical sense (and in fact a sailboat on jackstands at another nearby yard did blow over). He also said he thought Sandy would not end up being as hard on the Bay as forecast, and that was good enough for me. Moondust would stay at the pier in front of my house.

I wasn’t very worried about the initial northerly winds, which were forecast to gust up to 70 knots. I put double lines on Moondust, and added a wall of fenders. And I asked my neighbors if I could run lines from Moondust and the other sailboat at my pier to their docks. They graciously agreed, allowing me to diffuse the load among three different piers, while also introducing some long lines into the mix, which would add a shock cord element to the system. In the end, the boats ended up heeling to perhaps 20 degrees in the biggest gusts (the Chesapeake Bay Bridge recorded of gust of 90 mph, and sustained winds of 74 mph). But the line system worked perfectly. No lines snapped. No boats rubbed against hard wood. And no piers collapsed.

The only hitch was that while Sandy would track east and north, making landfall near Cape May, NJ, she would then head west into Pennsylvania before turning north and leaving the area. With her massive wind field (tropical storm force winds would stretch across a diameter of almost 1000 miles), that meant we would end up on the southwest quadrant of the storm and would experience very strong southwesterly and southerly winds (50-plus knots, forecast to gust over 60) before it was over.

Southwest is the one direction that is unprotected at my pier, as it opens up to a small bay of the Rhode River.

There is only about a mile or so of fetch, but my imagination started to conjure what sort of wave action, and surge, 50-knots of wind would throw up over that distance. I hoped that the forecast would change and ease, but if it didn’t, I wondered if I would regret keeping Moondust at the pier. To cope with this eventuality I got some lines to a piling outboard of my pier, and astern of both sailboats. I also kayaked out mid-creek and dropped a small, but sturdy, Danforth anchor onto the bottom, with perhaps 150 feet of scope. It dug into the bottom as soon as I started pulling it back toward the stern of Moondust, and I made it fast. The nylon rode, and all that scope, made a perfect springy spring line to prevent Moondust from jerking hard against her piling-fastened lines if big wave action started to roll up from the southwest and push her forward.

After all that, I hunkered down in the house to wait it out, and adjust lines as need be. Knowing I had done everything I could think of to protect Moondust, I relaxed. It was in fate’s hands now. Sandy blew ashore a day later. The winds howled from the north, as forecast, but that is the most protected direction for my pier. I constantly checked the local marine forecast for signs that the southwesterly would not be as bad as initially forecast. For a while it had the winds backing only as far as the west (a protected direction), and that was cause for a rum and tonic. But then the forecast reverted to a day of southwesterlies at 40-50 knots. Not good, but nothing I could do but wait and see.

As it turned out, Alex’s instincts were correct. Sandy blew in hard, but blew out at wind speeds less than forecast. I woke up to a gray, wet Tuesday morning, and the southwesterlies I had been fearing. But they were blowing at 25, gusting 30. It’s very rare that a Chesapeake sailor will consider 25 knots from the southwest to be light breeze. But after seeing gusts of 60-plus roll down my creek from the north, blowing spray off the water surface and howling fiercely, the southwesterly seemed positively meek.

There Moondust sat as the day got brighter. Bobbing easily to the wind and chop, secure in a web of lines and no worse for having endured Hurricane Sandy. So, two down, and no more to go (I hope).